Review: Rutherford and Son (Sheffield Crucible)

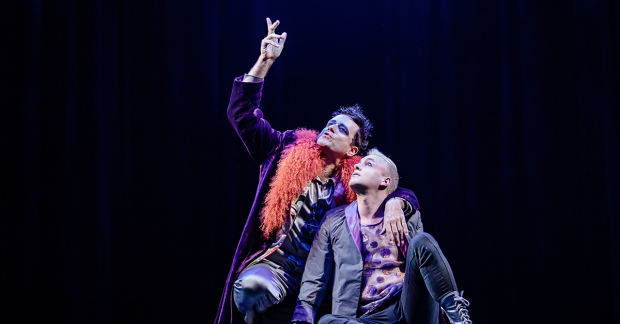

© The Other Richard

Githa Sowerby's 1912 play, Rutherford and Son, is one of the most astute and powerful of the dramas of the time dealing with social issues in a changing world, but the play's own history makes as strong an attack on traditional prejudices as its text. It was advertised as by K G Sowerby and the critics thought they had discovered the English Ibsen. When the author was revealed as a woman, admiration cooled: the play had a decent London run, but then disappeared from the stage until 1980. Since then regular revivals have ensued and this is, in fact, Yorkshire's second chance to see the play in six years, Northern Broadsides having produced a Yorkshire-ised version in 2013.

Rutherford and Son deals with an oppressive family tyrant who owns a glassworks in the North East; the inevitable generational divisions are exacerbated by his two sons' incapacity for business. And Sowerby knew of what she wrote. Her grandfather was such a character, but her artistic father was feckless with money and eventually Githa and her sister had to leave their comfortable middle-class life in Gateshead and earn a living in London.

Rutherford is a monster: his chair must not be sat in by anyone else, his daughter is peremptorily summoned to remove his boots for him. The basis for his tyranny is that he is a provider. Janet, his daughter, has been fed and warmed in idleness for all her 36 years; when John, his son, despite his public school education, is unable to make ends meet, he is taken into the firm and his wife, Mary, and child are received, if not welcomed, into the house. However, John, rather surprisingly, has discovered a new manufacturing process that will revolutionise the industry and is insisting that his father pay him the going rate for it. Richard, the other son, the local curate, wants to take up a post in Southport and Janet, desperately bored with the life her father imposes on her, has been carrying on an affair with the works foreman.

For a first play, Rutherford and Son is wonderfully assured in its pacing, dialogue and structure, except for an occasional tendency to over-stretch self-explanatory speeches. One of Sowerby's great skills is her ability to shift focus from one character to another. Marian McLoughlin's acidly amusing Aunt Ann, Rutherford's irrevocably traditional sister, dominates the first scene, with an unforthcoming Janet and a totally misunderstood Mary, then John's entry introduces his new process. All this is dominated by talk of Rutherford, but it's half an hour in before his meticulously prepared entrance occurs.

In the central role, Owen Teale is outstanding, dominant both physically and verbally, able to suggest that his ill-concealed contempt for his children is nothing personal – that's just the way they are, it's his duty to provide for them and theirs to obey him. Interestingly, though John's discovery seems likely to be the catalyst for Rutherford's problems, Janet and Mary emerge as much stronger than he is and Laura Elphinstone and Danusia Samal pace their performances perfectly, rising to key scenes later in the play. Ciarán Owens has less to work on as John, but convincingly brings out the weakness beneath his intelligence and charm.

Caroline Steinbeis' well-balanced and character-driven direction has one or two odd features – the over-dramatic music and added mime before the start and between the acts, for instance – but makes a powerful impression. In Lucy Osborne's spacious designs, factory wall and industrial gantries loom over the subdued comfort of Rutherford's dining room.