Long before Technicolor was even invented, the glistening green of the Emerald City had been realised in the flesh.

The largely forgotten musical of The Wizard of Oz was first staged in 1902, and the evidence remain like those left in the wake of a tornado.

In this special edition of Stage by Stage, we’re looking at The Wizard of Oz, which played on Broadway and across the US as a “musical extravaganza.”

It is worth noting that, unfortunately, much of the knowledge of original production has been lost to time, and it is with great thanks to the Oz enthusiasts and theatre historians who have chronicled enough to put together this brief overview of such a big, affecting work.

The yellow brick road to Broadway

L. Frank Baum always dreamed that his 1900 book, which introduced the world of Oz, would reach the stage. Just a year after publication, he worked up a first copy, before enlisting the help of the book’s illustrator, W. W Denslow, to design sets and costumes, and a young composer, Paul Tietjens, to write the lyrics.

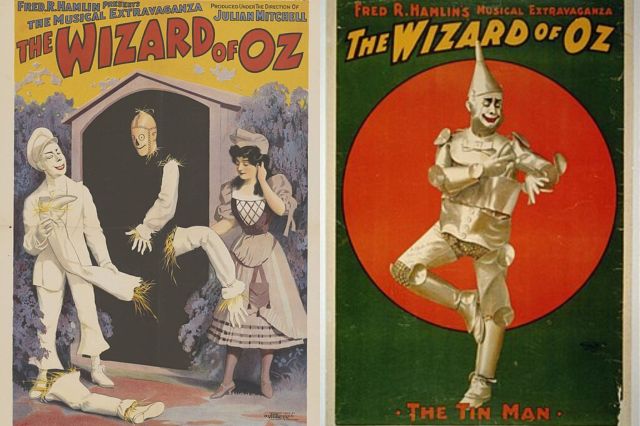

Soon after, Fred Hamlin joined as a producer. He’d just had a hit with Babes in Toyland, and while he clearly had a knack for producing family shows, it is widely believed that he signed up to this project in particular because his family had made their fortune (controversially) selling Hamlin’s Wizard Oil. Julian Michael became attached as director, outlining his vision of using the musical as a vehicle for celebrating the past 25 years of American music. He insisted that the Oz on stage were to become an Americanised fantasyland, complete with diners and streetcars. This worked for Hamlin, who coined “Fred R Hamlin’s musical extravaganza” and popped it on the posters.

As the production skipped toward Broadway, Tietjens reportedly struggled to provide the tin-can-alley pop tunes, and it reportedly began to take a toll on his well-being. Several lyricists, including Glen MacDonough, who wrote the libretto for Babes in Toyland, were called in to assist. Ultimately, A Baldwin Sloane is credited alongside Tietjens for the score, but it’s unclear how much of the work can be attributed to each composer.

In 1902, The Wizard of Oz, a three-act musical, premiered in Chicago before settling into its Broadway home at the Majestic Theatre a year later, while tours ran concurrently.

There are records suggesting that there were some 50 numbers (written by a variety of songwriters – details of whom can be found here alongside other creatives) used at various times in the run of the vaudevillian show, and many were altered in and out depending on where the piece was performing and what was popular at the time. Often, the runtime of the show would extend over four hours due to audience demands for encores, which helped determine which to keep.

Unfortunately, many of the numbers are lost today. However, David Maxine has collated as many old recordings as possible in an album: Vintage Recordings from the 1902 Broadway Musical The Wizard of Oz, which was nominated for a Grammy. It includes titles like “Come Take a Skate With Me” and “Mary Canary”. The award-winning and familiar work by Harold Arlen, E.Y. “Yip” Harburg and Herbert Stothart for the 1939 MGM movie will no doubt have been influenced by the original stage musical.

The Wizard of Oz was a hit on Broadway, playing for 293 performances – a feat unheard of at the time. Consequently, there was a fallout about the royalties. Both Baum and Denslow owned joint copyright, and the illustrator was convinced that he deserved more as a co-creator. Following the breakdown of their partnership, Denslow continued to use his illustrations of the characters of the Tin Man and Scarecrow in his own cartoons for commercial gain.

The Great and Powerful cast

Our knowledge of the cast of The Wizard of Oz survives through remaining play programmes, but there are gaps. However, the first performer to play Dorothy Gale – interestingly, our heroine’s surname was first introduced on stage and is not formally confirmed until Baum’s third book – was 19-year-old Anna Laughlin. She had been a child performer and elocutionist growing up, and also featured in silent movies.

It was a stroke of genius from Mitchell, who cleverly cast performance duo David Montgomery and Fred Stone as the Tin Woodman and Scarecrow, respectively. The pair performed regularly together prior to and following the musical, which launched their careers. Coincidentally, Stone was very good friends with Annie Oakley (the inspiration behind Annie Get Your Gun) and was left her unfinished autobiography following her death in 1926.

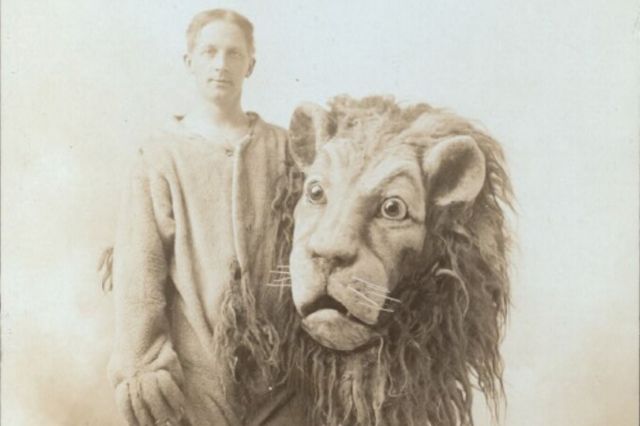

On stage, the Lion was reduced to a “bit part” and was a silent character, mainly used for laughs and performed as a traditional four-legged pantomime animal. Still, the character was much-loved due to the performance by Arthur Hill, who is today regarded as one of Broadway’s best animal impersonators. Hill remained with the show throughout its run and later married a member of the chorus, Alice “Stubby” Ainscoe. Together, when the rights became available, they staged an amateur production of the musical in Boston, with Hill reprising his role.

I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore…

There were many significant changes made for the stage production of The Wizard of Oz. The story of Dorothy and her friends’ quest to see the Wizard was much more about the politics of Oz. Toto is replaced by a cow named Imogene (bigger animal = bigger spectacle), and the Wicked Witch of the West is only mentioned, not seen, in place of a host of other characters. When Dorothy and Imogene are blown into Oz, they arrive with the former king, Pastoria, who was pushed out of power by the Wizard, so begins a quest for him regain his throne… only for it to backfire.

New characters included American waitress Trixie Tryfle, who is the prospective Queen of the Emerald City, and shop assistant munchkin Cynthia Cynch (also known then as Lady Lunatic), who was accused of being a witch, after her lover, the piccolo-playing Niccolo Chopper (guess who), went missing. There was also Sir Dashemoff Daily, the Poet Laureate of the Land of Oz, who was madly in love with Dorothy.

As we’ve discovered, the musical varied show to show and topical jokes picking fun at everything from politics to sports were written in. However, one thing that has stood the test of time in the franchise is the poppy fields, which were a new addition to the musical. Also, in the musical, Dorothy was granted three wishes (one of which brings the Scarecrow to life), and a ruby ring replaced the silver slippers.

If I only had a revival…

There have been many post-war revivals and productions inspired by the world of The Wizard of Oz. Three popular revivals are staged regularly professionally, and all use music from the film with Judy Garland:

- The 1942 St Louis Municipal Opera production, adapted by Frank Gabrielson.

- The 1987 Royal Shakespeare Company production, adapted by John Kane.

- And the 2011 adaptation by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Jeremy Sams, with additional music by Lloyd Webber and additional lyrics by Tim Rice.

Lloyd Webber and Sams’ version was first seen in the West End and was led by Danielle Hope, who competed against various stage stars to land the role in Over The Rainbow, a TV talent search show. Hannah Waddingham played the Wicked Witch and earned herself a WhatsOnStage Award.

It was revived at Curve, Leicester, by Nikolai Foster a couple of years ago, and enjoyed a summer in the West End before touring the UK extensively.

You don’t need us to tell you about the historical significance of The Wizard of Oz and its lasting effect on popular culture. Musicals like The Wiz and Wicked are two of the most impactful exports, while the original book and the famed movie continue to be enjoyed by generations.

Baum was determined to continue the stage success and wrote The Marvelous Land of Oz with the intention of a stage production. Additionally, he spent years working on The Tik-Tok Man of Oz (a musical adaptation of Ozma of Oz), which premiered in Los Angeles. A third attempt at a stage production was The Patchwork Girl of Oz, which instead became one of many films.