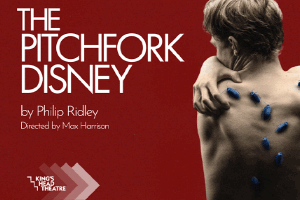

The Pitchfork Disney at King’s Head Theatre – review

Max Harrison’s revival of the Philip Ridley play runs until 4 October

Since starting out as a theatre critic in 2018, this is the first time I had already purchased tickets before being asked to review a show. Having read the 1991 Pitchfork Disney script at 17 years old, its jet-black whimsy and subversion had stuck with me, and I was delighted to have the opportunity to finally see it.

Unfortunately, my enthusiasm hasn’t aged well. While Ridley’s first and seminal work still maintains the shock and grisliness that so impressed me, it now feels aimless, with no message except to say: people are awful, even you. Lock your doors.

At 28, Haley and Presley are “ancient children”, afraid of the outside world, hiding in the flat they grew up in, and subsisting near entirely on chocolate and sleeping pills. But after knocking Haley out with a dummy full of meds, Presley decides to help a puking stranger off the street, risking his and his sister’s haven for a taste of the real world.

It’s no surprise that the script started out as two performance art pieces as part of Ridley’s studies at St Martin’s. This intense art school energy is maintained throughout, with little to no respite, and when the play starts so close to full throttle, where is there to go? Why, a full gimp costume of course, masking an incoherent, gasping monster named Pitchfork. At the point of Pitchfork’s appearance, we have only just completed a wild, visceral, disgusting shaggy dog story from Presley, so by the time the gimp costume appears, I am at capacity. No more. Except we’ve still got another half hour to go. Another half hour of discovering the depths to which humanity will willingly crawl.

In terms of the production itself, as directed by Max Harrison, there’s little to fault. All performances are gut-curdlingly magnetic: Elizabeth Connick as Haley is vulnerable and twitchy; Ned Costello’s Presley and William Robinson’s Cosmo have the most uncomfortable, palpable chemistry – their back-and-forth somewhere in the middle between monologues, is actually a play in itself, just two little boys competing to be the most revolting; even Matt Yulish’s Pitchfork is artfully looming, terrifying as a nightmare.

Kit Hinchliffe’s design is ideally drab, the brown and beige of an ‘80s British living room, incongruous with the reveal of Cosmo’s bright red sequined jacket.

Even Ridley’s script is witty and poetic; a brilliant character study. The problem is not the quality of the writing, but the content. Ultimately it feels like a young art student showing off, upsetting his audiences so he can say “see, the world is upsetting, I showed you that.”

But we don’t need a nightmare monologue about a little boy who appears as an old man, naked and defecating on the street with an erection to know that the world is a terrible place. And with not a glimmer of light in sight, it seems Ridley simply thinks we should give up.