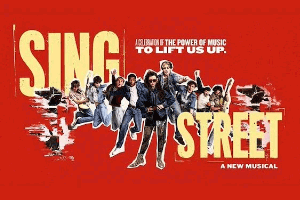

Sing Street musical review – lights up the London stage

The UK premiere production, directed by Rebecca Taichman, runs at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre until 23 August

The giddy possibilities of youth, the transformative power of art and the rebellious appeal of rock music crash resoundingly together in this gritty, wondrous musical several years in the making. Based on John Carney’s 2016 film, Sing Street premiered at New York Theatre Workshop, the downtown Manhattan powerhouse that developed Rent, Once and Hadestown amongst others: their collective DNA is palpable in this scrappy, open-hearted but deceptively well-crafted tuner that never made it to Broadway in 2020 due to the pandemic. New York’s loss is London’s gain.

It shares the same working class Dublin setting as Once, but the shadow of The Commitments also hangs over this tale of kids in the 1980s forming a band as a way of escaping challenging personal circumstances. Where that had a soundtrack of soul standards, this score, by Carney and Danny Wilson frontman Gary Clark, so accurately evokes the synth-heavy combo of uplift and heartbreak (or “happy-sad” as the script describes it) of the decade of big hair and shoulder pads, that it’s hard to believe these bangers aren’t pop hits from that era.

Perhaps the highest compliment one can pay is that they sound as irresistible as the ACTUAL ‘80s tunes that punctuate the evening in snatches of their original recordings. The band here (named Sing Street, after Synge Street, the tough Catholic school the youngsters are students at) is created because singer Conor (Sheridan Townsley in a stunning professional debut) wants to impress Raphina, a slightly older girl he’s randomly met.

So far, so sweet, but Enda Walsh’s book – punchy, hilarious, occasionally absolutely devastating – has multiple colours and layers, inspired by a screenplay that should be more known than it is. In the ‘80s, issues like neurodivergence and domestic abuse were dealt with in a less enlightened manner; Carney has created a gallery of people all struggling in their own way, and their stories are presented with insight and compassion while acknowledging the shortcomings in comprehension back in the day. It’s a tremendously kind show steeped in harsh realities yet spiced up with irresistible flights of fancy and a nostalgic glow.

Conor’s older brother Brendan (Adam Hunter) hasn’t left the house in months but had musical ambitions, school bully Barry (Jack James Ryan delivering an unsettling, riveting mix of terrifying and tender) has more to him than meets the eye, the band’s pianist (heart-catching Jesse Nyakudya) harbours a deep melancholy that music relieves, and love interest Raphina has endured a lot of trauma for one so young. Grace Collender is extraordinary: a beautiful but damaged young woman vacillating between the aloof power her looks afford her and the desolation of a soul let down early in life by the people she should have been relying on. It’s a beautifully intense, detailed piece of acting, then when she sings there are shades of Kate Bush at her most haunting.

Townsley is equally astounding, charting the journey from gauche schoolboy to androgynously sexy rock god with total conviction. The riveting, endearing Hunter as the brother reduced to living out his early promise through his better adjusted younger sibling is the third beating heart at the centre of this engrossing story. It’s typical of the off-the-wall nature both of Walsh’s book and Rebecca Taichman’s fluid, captivating staging that the heart-soaring closing moments aren’t given over to the young lovers, or even the band, but to this noble stoner whose ultimate ability to overcome his own demons is a final triumphant air punch in what is an evening of constant emotional and musical highs.

The charismatic young company of actor-musicians is a joy, whether swapping instruments in Clark and Peter Gordeno’s bracingly exciting arrangements or bouncing through Sonya Tayeh’s choreography that galvanises yet always looks like real people dancing. Lloyd Hutchinson lends genuine darkness as the Catholic school master whose pent-up aggression makes sparks fly, and Lucianne McEvoy, Lochlann Ó Mearáin and Jenny Fitzpatrick are vivid and persuasive as parents whose lives are as chaotic as those of their offspring.

Every aspect of the production feels fresh and exquisitely executed, from Natasha Katz’s lighting to Luke Halls’ video design and Bob Crowley’s evocative, malleable setting. The costumes by Lisa Zinni scream authentic 1980s but are never parodic. There’s no better sound designer than Gareth Owen for elevating rock and pop into theatrical nirvana, and his electrifying contribution here matches his work on extravaganzas such as Hell’s Kitchen and MJ.

In a remarkable example of having its cake and eating it, Sing Street is infused with a rich humanity that explodes into a roof-raising full-on gig as the band finds its ultimate footing, before retreating to a tear-inducing conclusion that puts the characters back front and centre. It’s a show that celebrates great music, the importance of human connection, the thirst to broaden one’s horizons, and the hopeful, exultant swagger of youth. A thumping great night out.