Michael Coveney: Musical metaphors as Rigoletto reigns and Snoo stirs

”Stephen Ward” shutters as the ENO reinvigorates ”Rigoletto”

The opening of a new musical, The A-Z Of Mrs P, at the Southwark Playhouse last night coincided with the announcement that Stephen Ward, which opened ominously at the Aldwych on the night the ceiling caved in at the Apollo, will close at the end of March, some time earlier than originally scheduled.

Curiously enough, both musicals start promisingly and nose-dive in a bog of a second act. And this only goes to show that experience is no guarantee of success: a good musical is the hardest thing on earth to write. Stephen Ward was the work of Andrew Lloyd Webber, Don Black and Christopher Hampton, who've all been round the block several times, to put it mildly.

The A-Z Of Mrs P is written by Diane Samuels and Gwyneth Herbert, put together by producer Neil Marcus to produce what they call an intimate, epic work of psycho geography that celebrates what it is to struggle with family demons. Samuels has written a few lyrics before, but Herbert had not even, when first approached, seen a staged musical in her life.

The trouble with the end result is that the family demons do not really relate to the task in hand, the mapping of a city, and once the inspiration for compiling the A to Z runs out, the writers are left filling the holes with slabs of psychological hysteria. The same thing happens differently in Stephen Ward, where the narrative emphasis keeps shifting from the central character to the underworld activities of Christine Keeler and then the victim status of Valerie Hobson, John Profumo's wife, who has the best song in the show and that's it.

The performance of a rousing chorale from Titanic (seen last year at the Southwark Playhouse) at the WhatsOnStage Awards Concert on Sunday was a reminder of how important is the layering of a libretto in a musical. Titanic is by no means a masterpiece, but its structure is exemplary, and the control of the narrative strands totally responsible for the accumulative power of the music.

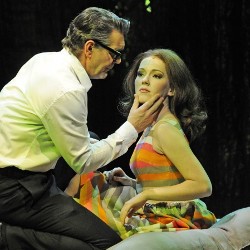

A good opera works in exactly the same way, and the new revival of Rigoletto at the ENO is a case in point. Christopher Alden's production is staged as Rigoletto's nightmare, not at the court of a Renaissance duke, but in the panelled, luxuriant confines of a 19th century gentlemen's club, where the maltreatment of women is a metaphorical extension of the sexual exclusiveness and braggadocio of the members.

To complain, as some critics have done, that we don't have a riverside tavern in a murky light, nor a fateful body bag at the end, is surely being over-literal. The staging here is deliberately spiritual, almost hallucinogenic, and the conclusion of the story all the more shattering as a result. You want realism, you want murk, you get David McVicar's revival for the Royal Opera.

You got those things, too, in Jonathan Miller's famous ENO revival which this one replaces in the repertoire (oddly enough, Alden uses the same fine translation Miller elicited from the poet James Fenton). That 1982 version transposed the court to a 1950s Little Italy and a bar that might have been painted by Edward Hopper where the most famous tune, "La donna e mobile", was started with a firm kick of the jukebox. I loved the Miller production, but I love this one too. It's particularly interesting to have the setting returned to the time of the composition, something Miller himself often does; the music sounds absolutely right.

It sounds even more right under the conductor Graeme Jenkins, who never dawdles, and in the magnificent singing performances of the Hawaian baritone Quinn Kelsey – whose shambling, tragic bulk as the clown evokes the spirit of Charles Laughton as Quasimodo – Anna Christy as Gilda and Barry Banks as the Duke, small and sinister with a voice as dry as a fino sherry.

The scope of these performances – their infinite possibilities – are far beyond anything in either The A-Z Of Mrs P or indeed Stephen Ward. Good acting, good theatre, can only derive (usually) from the talent and the richness of the writing, something that was powerfully borne in on me as I sat listening to Simon Callow, Lesley Sharp and Clive Merrison reading from the plays of Snoo Wilson at the National Theatre's Platform performance last Friday.

I had made my contribution in a quick critical assessment, and Howard Brenton told a wonderful story of an altercation in a motorway cafe as he and Snoo toured the country in Portable Theatre's bus at the end of the 1960s. But when the actors spoke, we heard the true dazzle and pungency of Snoo's writing and I went home convinced that someone – ideally the new Bush Theatre, perhaps – should present a season of his plays.

Actually, I didn't go home that night until I'd sat through Blurred Lines in the NT Shed. As this rather thin collection of feminist vignettes featured some of my favourite performers, including Claire Skinner, Marion Bailey and Ruth Sheen, I didn't really begrudge them 75 minutes of my company, although the phoney Q&A at the end sorely tried my patience.

Above all, you felt this was fringe theatre on automatic pilot, safe and uncontroversial, polite and slightly pleased with itself. What's needed is a good dose of Snoo, or something like him, to shake it all up again. The next day, I received an email from his friend and fellow Portable Theatre playwright, Tony Bicat, picking me up on a too-loose reference to Snoo's surrealism.

"I think it's the perennial problem," Bicat says, "of trying to fit Snoo into some kind of category – like stuffing a large duvet into a small draw. Yes, he was a bit surrealist also a bit absurdist also a bit a lot of other things… he was I think in a line of English eccentrics and innovators – Sterne, NF Simpson, Douglas Adams – but without any trace of English whimsy or sentimentality. Most of all, whereas other dramatists are similes, he was metaphor! It was good to hear his work again let's hope a new generation will be bold enough to put it on." Here's hoping…