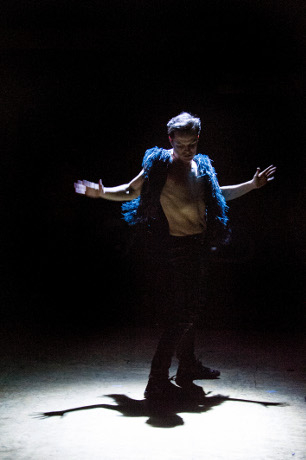

Matt Trueman: Andrew Scott makes theatre more dangerous

Matt Trueman on the unpredictable joys of ”Sherlock” star Andrew Scott

© Marc Brenner

Andrew Scott though. I’m not often one to fanboy, but let me say this: Andrew Scott, Andrew Scott, Andrew Scott. My god. There isn’t a more electrifying actor on stage at the moment. Hasn’t been for years, really. Not even close.

Last week, I caught up with The Dazzle, Richard Greenberg’s three-hander at Found 111. Actually, that’s not entirely true. More accurately, I caught up with Andrew Scott’s performance in The Dazzle because I spent the whole show watching him. Greenberg’s play (not his strongest) only vaguely registered. Even with David Dawson on the form of his life, even with Joanna Vanderham’s eyebrows, I couldn’t take my eyes off Scott.

In fairness, that’s almost impossible. Scott is a livewire presence on stage. Where his Sherlock co-star Benedict Cumberbatch has a classical, commanding star quality, where Rory Kinnear has an intricate intellectual approach, where Ben Whishaw is ethereal and enigmatic, Scott is singularly, thrillingly, dazzlingly unpredictable. He’s impish, mischievous, playful and knowing – always fully aware of being watched and, you suspect, relishing an audience. Some actors have kinetic energy. Others have a gravitational pull. Scott is pure potential. When he’s onstage, anything could happen. He makes theatre more dangerous.

Scott was one of theatre’s best-kept secrets.

In The Dazzle, he plays a concert pianist with senses so fine-tuned that he registers the specifics of everything that exists. He can turn into a note to the slightest semitone and take in every single shade in a whole head of hair. It makes the world overwhelming; an Aladdin’s cave of individual wonders, many of which he hoards into the flat he shares with his brother (played by Dawson).

© Richard Hubert Smith

What makes Scott’s performance more than a standard-issue portrait of eccentricity or mental illness is his sense of his own presence in the room. It’s not that he pulls focus, per se, but Scott’s always up to something: bending his fingers back while listening, for instance, or springing up onto a piano from nowhere. His acrobatics are as often vocal as physical. He can stretch sentences out of shape, rattle through phrases, hiss words then holler. He acts like Lionel Messi plays football, with absolute flair and at full speed. There’s simply no getting ahead of him, almost as if he makes his decisions in the moment, as if he acts on a whim. His presence is absolutely immediate.

It’s what makes his Moriarty so perfect. Just as Heath Ledger’s Joker can outfox Batman, Scott’s Moriarty can get one step ahead of Sherlock – no matter how brilliant his rational brain. Watch his first appearance in those Victorian baths: the way every decision is unexpected, every sentence he speaks snaps into shape at the last second. You never know which way he’s going.

That scene changed his career – and kudos to casting director Kate Rhodes James because, before then, Scott was one of theatre’s best-kept secrets. I first clocked him in Mike Bartlett’s Cock at the Royal Court, another show in a tiny space, and was instantly rapt. As M, the boyfriend of Ben Whishaw’s flip-flapping John, he became the play’s stick of dynamite: initially sympathetic, standing his ground and allowing his partner space, he eventually exploded like a nuclear device. I swear his eyes turned black. His final victory – having snared his partner like prey – was as cold and as vicious as liquid nitrogen.

Of course, he’d been working for a decade by then. (Not that you’d know it, but he’s 40 these days.) After a few years onstage in Dublin, his birthplace, he first came to London in Conor McPherson’s Dublin Carol at the Royal Court in 2000. He worked mostly in new writing – Crave, Dying City, Roaring Trade – but it was a Simon Stephens monologue, Sea Wall, that really put the boosters on his career.

He's always fully aware of being watched and, you suspect, relishing an audience

First seen at the old Bush Theatre, when its lights weren’t working, Sea Wall let Scott share the space with us. It let him, maybe for the first time, shine through the text – his personality, his presence, his pyrotechnics. He seemed to share jokes with us, to toy with the very act of storytelling itself, all the better to jump us with the play’s emotional kicker at the end. And, oof, what a kicker. That black-eyed darkness dropped in again and Scott suddenly resembled a man with a hole running through him, a man missing a major part of himself. (Seriously, watch the film for yourself.)

Ever since, he’s had an ability to dazzle an audience. I missed him in Design for Living at the Old Vic, but who else could have found the demi-godliness needed to carry Ibsen’s four-hour epic Emperor and Galilean at the National, or the shimmering sexual vanity of a peacocking rockstar in Simon Stephens’ Birdland.

In this country, we have a tendency to measure great actors by Shakespeare and, for whatever reason, Scott’s never done any. I suspect the meter of verse might disarm him somewhat – that knack for renegotiating rhythm and toying with sentences – but what I wouldn’t give to see his Hamlet or his Richard III. Both thrive on their unpredictability – Hamlet in his madness, feigned or otherwise; Richard as a quicksilver Machiavellian – and Scott is more thrillingly unpredictable than anyone. Someone make it happen.