Man and Boy at the National Theatre – review

Anthony Lau’s revival of the Terence Rattigan drama runs in the Dorfman Theatre until 14 March

In 1963, when Man and Boy premiered, Terence Rattigan’s name was mud. Once the most feted playwright of his age, he had fallen completely from favour in the wake of the theatrical revolution of the 1950s, which swept playwrights such as John Osborne to relevance and popularity. Man and Boy signified the depth of his decline: a short run in the UK was followed by a disappointing 54 performances on Broadway.

It’s rarely performed even now. While other plays by Rattigan (such as The Deep Blue Sea or The Browning Version) are accepted as masterpieces, the last British production of Man and Boy was 20 years ago, starring David Suchet as the financial colossus Gregor Antonescu in a corner as his Wall Street empire starts to collapse, seeking refuge with his estranged son.

But seen in Antony Lau’s fast-paced, urgent revival, Man and Boy emerges as a surprisingly hard-edged play, upsetting in its subject matter and fierce in its execution. Watching it in the light of the Epstein scandal, it feels pressingly pertinent in its depiction of a valueless world where everything has a price – even love. With the peerless Ben Daniels outstanding as Antonescu, it has a savagery and sharpness that make it utterly compelling.

The play is set in the 1930s, after the Wall Street Crash and when the early rumblings of facism in Europe are becoming louder. Lau dispenses with its comfy realism and lets it play out on a green baize-covered square, with a great billboard of the type used to advertise King Kong, flashing the names of the characters and the actors as they enter. Aspects of Georgia Lowe’s design are gimmicky – the “Knock, Knock” flashing above the assumed doorway, for example.

Others are exhausting: the characters are constantly jumping up onto a table. Angus MacRae’s drum-and-trumpet jazz score tumbles threateningly in the background throughout. But the art deco starkness and the lack of naturalism focus the action and the power struggles perfectly. Elliot Grigg’s lighting serves the same purpose, shining a spotlight on Antonescu as he twists and turns to save his skin.

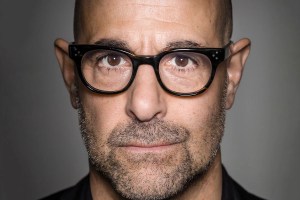

Daniels is magnificent. We first see him waiting to enter, black raincoat buttoned up to his neck, his face impassive, his profile eagle-like. As he greets his son Basil (Laurie Kynaston) and his girlfriend Carol (Phoebe Campbell, all nervous curiosity and openness), he’s like a force-field of energy, with a serpentine, seductive charm that can’t quite disguise either his anxiety about his ruin or his essential toughness.

He’s a master of the universe, bestriding the stage like a colossus. Aline David’s choreography uses the table to play games with power, making characters taller and smaller as their influence waxes and wanes. When Antonescu thinks he has saved himself, he stands on top and punches the air. “The man is still the thing!”

It’s a sickening image. What shocked people about the play, and what still seems appalling, is the way that to salvage his business, Antonescu is prepared to sacrifice his son, offering him (without his knowledge) as an enticement to his secretly gay rival (Malcolm Sinclair). It pivots on the way that he recognises that he cannot afford to love his son – or let his son love him – if he is to be truly ruthless. “Love is a commodity I can’t afford,” he says.

For the story to work, the horror of the father’s betrayal has to be matched by a limitless and enduring love from his son. Kynaston brilliantly conveys both Basil’s horror at his father’s actions as well as the enduring affection that cannot be destroyed. Every time he is knocked down, he climbs up again to offer his loyalty and some unkillable quality of filial devotion.

The strength of the playing of the central relationship is buttressed by Nick Fletcher as Antonescu’s assistant, both subservient and self-serving, and a cameo from Isabella Laughland as the abrasive betrayed wife. “All I’m really good for is sex and signatures,” she says, as she rifles her charity foundation to clear her husband’s debts.

The clarity of Rattigan’s writing, his wounded observation of how the world can be corrupted when men use power for profit and without concern for women, children or really anyone else around them, still sounds like a clarion call. Man and Boy may not be Rattigan at his humane best, but this stringent revival makes it clear how much more loudly he still speaks than many playwrights who succeeded him.