Here There Are Blueberries at Stratford East – review

The UK premiere production, conceived and directed by Moisés Kaufman, runs until 28 February

If you’ve seen Jonathan Glazer’s 2023 movie The Zone of Interest, where the family of Auschwitz’s Nazi commandant, Rudolf Höss, lead a life of comfort and privilege while inhumane horrors unfold in the death camp metres from their well-appointed home, aspects of Here There Are Blueberries will feel queasily familiar.

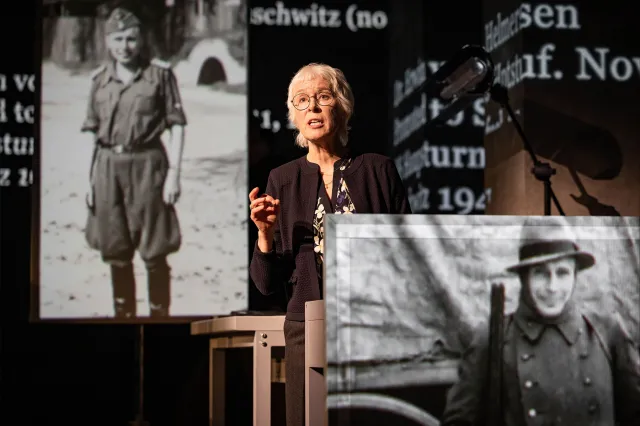

More expertly honed documentary theatre than conventional play, Moisés Kaufman and Amanda Gronich’s script – for the groundbreaking, investigative American company Tectonic Theater Project – is inspired by the delivery of a recovered 1940s photo album delivered to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2007. All the pictures were taken at Auschwitz and show Nazis merrily at work and play in the notorious Polish camp, but with no trace of the prisoners/victims.

The play’s title is a translation from the German of the caption underneath a photo showing a gaggle of uniformed secretarial workers, all but one of them women, enjoying bowls of blueberries in the open air. What’s so astonishing is how carefree and relatable they look, despite being part of the infernal Nazi death machine that murdered over five million Jews, as well as countless Romani, homosexuals, disabled people and anybody else who didn’t fit in with the fascist regime’s narrow margins of what constituted a true German.

Eight fine actors multi-role as museum staff, the descendants of those featured in the photographs, and survivors of that torturous time. The uneasiness felt by some at taking the focus away from the victims is deftly expressed. There’s little dialogue, the text mostly comprising a series of monologues – reflective, conciliatory, defensive, occasionally devastating – and the delivery is deliberately low-key, allowing the perpetrators, the victims, the offspring and the academics to speak for themselves. Information is delivered in a matter-of-fact manner that gains in power as the enormity of what they’re talking about becomes ever clearer, and the sense of inherited trauma is palpable. A descendant of Höss appears – a troubled, formerly violent American, convincingly played by Arthur Wilson – and concludes that “it’s my best revenge – to live my life differently… and tell the truth of who I am.” By contrast, Clifford Samuel radiates a cautious, watchful goodness as another scion of the atrocities who chooses to repudiate his heritage by bearing witness.

It’s the overall lack of histrionics that lends the play what dramatic force it has. An apparently ordinary woman (Kirsten Foster), one of the blueberry-eating girls in the photograph, confirms that they knew exactly what was being perpetrated just out of shot: “if you’re trying to build an empire, you can’t afford to be squeamish”.

Here There Are Blueberries invites us as spectators to ponder what we would do under the circumstances that the apparently innocuous figures in those black and white photos were living under, and to uncomfortably reflect on how ordinary those images are. The relevance to a present-day world in turmoil is inescapable. If you’re looking for traditional drama, you won’t find it here, but the gravitas, incredulity and the sheer awful scale of the Nazi horror are undeniably there, lurking beneath the sanguine words, demanding that attention be paid. The controlled vitality of the performances versus the static nature of the photographs, projected all over Derek McLane’s muted laboratory set, imparts an in-built tension to an evening that, for all its accomplishments, occasionally makes you wonder why this needed to be a piece of theatre.

Kaufman’s staging is beautiful in its simplicity, with David Bengali’s projection designs and Bobby McElver’s vivid soundscape doing a lot of the heavy lifting. The stark elegance and technical sophistication of the presentation sit in telling, potent contrast to the grim facts and human frailties, failures and cruelties laid bare in the text.

Fittingly, the final monologue goes to a Holocaust survivor ripped from her family upon arrival at Auschwitz because she was the only one deemed fit to work. Philippine Velge delivers it beneath a photograph of the real woman, with a heartbreaking simplicity, full of raw emotion but never self-indulgent. It’s a haunting moment in an evening studded with them.

This is a challenging, noble start to Lisa Spirling’s tenure as artistic director at Stratford East.