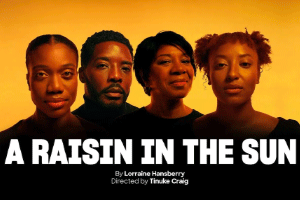

Headlong’s A Raisin in the Sun at Leeds Playhouse and on tour – review

Tinuke Craig’s revival runs until 28 September before touring to Oxford Playhouse, Lyric Hammersmith Theatre and Nottingham Playhouse

Since its first performance in 1959, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun has existed as a marker in American drama. The first play by a Black woman to hit Broadway, it then proceeded to scoop most of the awards going. Seeing it 60-plus years later, its power is undiminished, its mixture of humour, tragedy and humanity still as potent as ever. Tinuke Craig’s production for Headlong, in association with several theatres, consistently hits the mark despite the occasional lurch into melodrama, notably in the over-dramatic music.

It’s interesting to compare the play with what was happening in Britain at the same time. Critics squawked in horror at the sight of a woman ironing in Look Back in Anger; here the play begins with Ruth ironing, but I know of no similar outcry. There were more pressing concerns: as Hansberry herself said, audiences were astonished to be confronted with the simple fact of Black everyday life.

The Youngers are not dirt-poor: they live in a seedy apartment in Chicago, but they have aspirations. The daughter Beneatha has dreams of becoming a doctor, not to mention taking up the latest fads (guitar this time) and having a very rich boyfriend; the son Walter Lee has had his dreams crushed through years of working as a chauffeur and has drifted out of love with his wife Ruth who still loves him, though often cloaking it in a bad temper.

The trigger for the action is the imminent arrival of a cheque for $10,000, payable by the insurance company on the death of the father. What to do with it? His widow Lena wants to divide it between Beneatha’s education and buying a house; Walter Lee wants to put it into going into business with his dodgy cronies, Bobo and Willie. Lena puts a deposit on the house, then gives Walter Lee the rest to divide between Beneatha’s schooling and his own business venture. Willie disappears – and so does the money.

The play starts with questions about all kinds of issues; for instance, what does it mean for a Black man to rise in the world? To Walter, it’s all about money (When did he stop caring about freedom, his mother asks?); to Lena and Ruth, it’s a matter of acceptance, the purchase of a house in Clybourne Park a base for family life; Beneatha sees rising as working in a respectable profession.

The hopes of a peaceful move are ruined by a visit from “the man”, head of the welcoming committee at Clybourne Park, in a wonderful scene where Hansberry’s writing is matched by performance and production: Jonah Russell struggling through embarrassment to try to make the point that they will not be welcome in a whites-only environment.

It is this persistent presence of “the man” (also represented by the phone calls from Walter’s boss – very nice and polite, very threatening) that represents what Black people are striving against – after all, the only real crime committed is by a Black man, Willie, running off with the money, but fighting against assumed inferiority is tiring. And that’s where Beneatha’s other boyfriend comes in, Joseph (Kenneth Omole), a Nigerian who has dreams for his country.

One other reason for the success of the play is that it’s full of superb acting parts which Craig gives full relish to. Walter moves from resentful parenthood to explosive fury to drunken irresponsibility to finally growing up – all accomplished in a joined-up performance by Solomon Israel. Cash Holland, all the while on the brink of losing control, operates at high decibels as Ruth. Doreene Blackstock projects dignity as Lena, only once adding to the hysteria surrounding Walter Lee’s betrayal. Joséphine-Fransilja Brookman is huge fun as Beneatha in the first half, adopting every trend and posture going, but eventually convinces us that her desire to be a doctor is genuine. Beneatha’s boyfriend George is portrayed splendidly stiff by Gilbert Kyem Jnr. And finally, Ruth and Walter’s son, Travis, completes the family in a hugely accomplished performance by Josh Ndlovu, one of three alternating the role in Leeds.

Sadly Lorraine Hansberry – “young, gifted and Black”, in her own words – died far too soon, leaving a clear pathway for the likes of August Wilson.