Hamlet at the National Theatre review – Francesca Mills provides the heart in an insightful production

Robert Hastie directs his first production as deputy artistic director at the venue

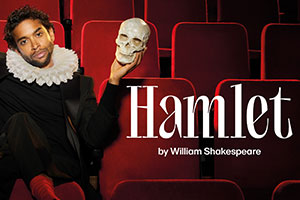

A star is born in this new production of Hamlet, the seventh in the National Theatre’s history. It isn’t the Prince, played by Hiran Abeysekera, but Francesca Mills’s Ophelia who brings this intelligent, thoughtful production to its most vivid life.

Mills has achondroplasia, the most common form of dwarfism, but that is the least relevant thing about a performance that illuminates and elevates every scene in which she appears. More relevant is the fact that she is a recent winner of the Ian Charleson Award, a remarkable metric of talent, named after one of the National’s most famous Hamlets.

The qualities she brings here are honesty and directness. Her Ophelia is funny, angry, and heartbreakingly betrayed by a man she thought might love her. Robert Hastie’s direction, which is full of telling detail, makes the songs she sings when she goes mad those that she used to sing with her family, whom she loved, before her world collapsed around her.

Hastie brings that kind of insight to scene after scene, creating consistently wonderful moments in a staging that uses the bulk of Shakespeare’s text but plays it so fast that it runs for just under three hours. Though it is played in modern dress, Ben Stones’ imposing set of a high-ceilinged banqueting room with frescoes of war and peace painted on its walls, lends a timeless feeling.

It also, in the opening scene, makes for a genuinely scary ghost hunt, lit only by torchlight, with Hamlet’s father appearing and disappearing as if by magic. This care to see the play afresh is everywhere apparent. Geoffrey Streatfeild’s Polonius is a tiresome, meddling bureaucrat, but he is also a kind and loving man who sympathetically touches Hamlet’s shoulder when he sees his grief. Laertes (another lovely, sensitive performance from Tom Glenister) and Ophelia chant along with him when he starts dishing out advice; they are a real family. Ophelia’s sense of loss after his death is utterly convincing.

At the same time, Alistair Petrie superbly turns Claudius into exactly the man Hamlet isn’t: courageous and decisive. But he also endows him with self-knowledge and doubt. The play scene, where Hamlet confirms his uncle’s guilt in the murder of his father, is brilliantly staged. Within a setting of red drapes, the players give an impersonation of what might be a Jamie Lloyd staging of Shakespeare – using microphones and standing still – while Hamlet, a ruff topping his T-shirt, uses another microphone to comment on the action.

But the real stroke of genius is to let Claudius return to the empty theatre, to confide his guilt to the audience sitting in the Lyttleton stalls. This consciousness of an audience, of the essential theatricality of Hamlet as a play, runs through the production.

Which makes it all the odder that Abeysekera – the National’s first Asian Hamlet – makes so little of the soliloquies, those moments when he actually takes the audience into his confidence and reveals his thoughts. He comes to the very front of the stage, bathed in Jessica Hung Han Yun’s clear light, but then races through them as if anxious to get to the next scene.

His interpretation is completely coherent. This is Hamlet as a sulky, childish young man, funny and irresponsible, scared, skittish and completely unable to cope with the demands laid upon him by his life. He can barely load the gun in his hand, and flinches when faced with violence. He’s constantly on the move, with a truly hectic disposition, jumping around the stage, letting out oohs and aahs of excitement and surprise. By the time he confronts his mother, seeing a ghost the rest of us can no longer see, he appears to have truly lost his mind.

It’s original to see a Hamlet who isn’t a melancholic poet, but the disadvantage of the approach is that it strips the play of its thoughtful centre. As he showed in both Life of Pi and The Father and the Assassin, Abeysekera is an actor of charm and presence; here, he seems deliberately to sacrifice both. When he curls up in a foetal ball to die in the arms of Horatio (a gender-swapped Tessa Wong), he is pitiable rather than tragic.

That is, of course, the wonder of Hamlet. Every version challenges previous views of the play, making it new. Hastie has provided a handsome, clear-sighted production. But it’s Mills who provides its heart.