Guest Blog: 'Like Johnny Got His Gun, Dalton Trumbo is an American classic'

Bradley Rand Smith, whose 1983 adaptation of Dalton Trumbo’s ”Johnny Got His Gun” is revived at Southwark Playhouse this week, says if the author was around today he would share a drink with Edward Snowden

Dalton Trumbo died in Los Angeles in 1976. I had just graduated high school in Colorado (not far from where Dalton was born and raised) the year before, when I first read Johnny Got His Gun; I'd just missed the last draft for the Vietnam War.

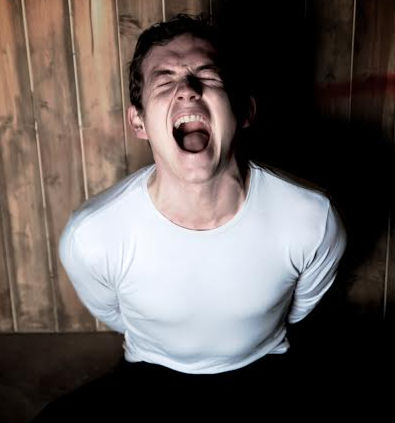

I never had the privilege of meeting Dalton, though I went on to adapt his award-winning novel into an award-winning play. For the uninitiated, it centres on a young American who returns from World War One to discover he's become what used to be cruelly called "basket cases," because you could carry what was left of the still living body in a basket.

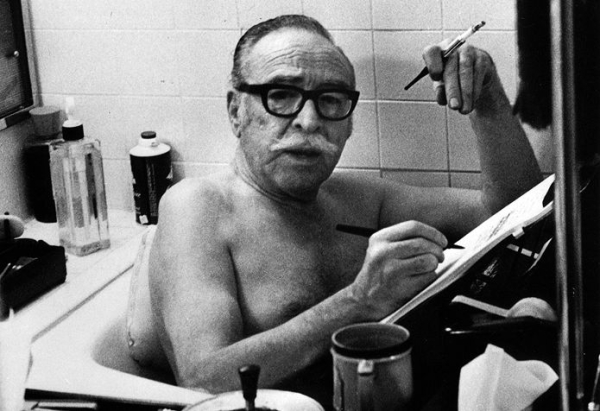

Like Johnny Got His Gun, Dalton is an American classic; just look at a later photo of him with the weathered skin, bushy moustache and dark framed glasses and one could easily imagine him playing a Hemingway character, or even Papa himself – not hunting wild game with ruthless abandon, but using words and stories and his own life as acts of personal courage.

It must have taken a degree of courage to write Johnny Got His Gun, one of the greatest anti-war novels ever written, and write it with such gut-churning honesty and righteous anger at a time when institutionalised murder was still very popular (and before war became America's biggest export).

Dalton wrote over 40 scripts, becoming one of Hollywood's highest paid and most prolific writers. His credits ranged from Lonely Are The Brave to Spartacus, Exodus, Papillon and Roman Holiday, for which he won his first Oscar (his second was for The Brave One).

© Anna Soderblom

If there are any creative threads running through Dalton's scripts and his life, they are discussions of personal responsibility, personal conscience and personal integrity; even the young princess in Roman Holiday challenges the status quo and asserts her personal rights as she sneaks out of the palace and spends a raucous evening among the '99 per cent', if only for a night.

When Dalton decided to make a film of Johnny Got His Gun in 1971, he decided to make it himself, putting his personal finances and those of fellow producers at great risk, creating what many consider the first truly independent American film. He even cast Donald Sutherland as Jesus overseeing a poker game of young soldiers heading to their death. Perfect. And he didn't sugarcoat the story for audiences. The film went on to win the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury Award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Dalton was a communist in the mid-40s when many people of conscience were, though he had resigned by the time he was called to testify before the House Committee On Un-American Activities in 1947 (a wonderfully ironic and accurate Congressional committee name if there ever was one), where he refused to 'name names' of fellow suspected communists in Hollywood. It was an act of personal conscience that earned him 11 months in a federal prison. (I had the opportunity to spend some time with Ring Lardner, Jr. in 1982, who was a fellow prisonmate of Dalton's, who made it clear that they were not housed at a 'tennis court prison' but at a very real prison for their 'crime' of upholding the Constitution and Bill Of Rights.)

Afterwards, Dalton was blacklisted by Hollywood, forced to leave the US with his family and write scripts in Mexico under pseudonyms, or using other writers as 'fronts'. It was only when Otto Priminger hired Dalton to write Exodus and Kirk Douglas hired him to write Spartacus in 1960 under his real name that the blacklist was broken, 13 years later.

A couple of folks I believe Dalton would share a drink with these days, when personal conscience and integrity amount to little more than not getting caught, are Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning. It's easy to write about honorable intentions and scold those who don't live up to them from behind anchor desks and blog posts and political shout fests, it is quite another to walk the talk and face the consequences of one's actions.

Bryan Cranston is scheduled to play Dalton in the film of his life – a fitting match for the actor who made Walter White a symbol of defiance of the status quo – so he will no doubt be discussed and debated afresh in the coming months and years.

But Dalton has nothing to apologise for. His conscience is clear. He is resting easy.

Johnny Got His Gun runs at Southwark Playhouse from 21 May to 14 June 2014