Crocodile Fever at Arcola Theatre – review

The London premiere of Meghan Tyler’s Edinburgh Fringe show runs until 22 November

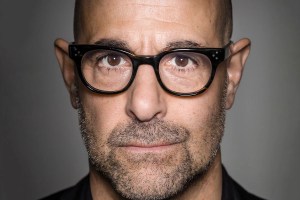

Northern Irish writer and actor Meghan Tyler’s 1980s Troubles-set play Crocodile Fever was first performed at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2019, and it now makes its London debut in a new production by Arcola Theatre artistic director Mehmet Ergen, with Tyler this time playing the co-lead role of Fianna.

The scene is set for kitchen-sink drama: a young woman dressed like a 1950s housewife is fastidiously cleaning the hob with a toothbrush when a rock is thrown through the window and her chaotic sister Fianna climbs through. The two haven’t seen each other for over a decade since Fianna went to prison for causing a fire that killed their mother, which the buttoned-up Alannah in fact started.

As their paralysed father lies in wait upstairs, the estranged sisters bicker, catch up on the “craic”, and consume copious amounts of gin and whisky during the somewhat leisurely-paced first act. Alannah explains her convoluted interpretation of the song “Africa”, which she has always believed to be about apricots, and Fianna is impressed by the way in which her mind works in such an unusual way. The play also makes use of Tony Bennett singing “You’ll Never Get Away from Me” (originally from Gypsy) as a twisted family anthem, just as it has elements of emotional abuse in its original context.

Rachael Rooney is superb as Alannah, whose performative prissiness, which has evolved into full-on OCD, is her weapon of self-protection. In one memorable sequence, she makes a piece of toast with ostentatious precision “like it’s a sacrament”. As the bull-in-a-china-shop-esque Fianna, who “could eat a wreath from a hearse”, Tyler communicates the vulnerability beneath the gun-toting, chainsaw-wielding exterior. Their father (Stephen Kennedy) is uncannily relaxed in spite of the gruesome injuries inflicted upon him by his daughters, but there’s clearly an underlying malevolence, by an appallingly misogynistic “joke”.

Tyler provides all the ingredients for a family drama in which the sisters argue and secrets are revealed. They eventually come to some kind of mutual understanding, with a Martin McDonagh-cum-Tarantino-style influence that makes way for female-led horror.

Tyler’s writing is filled with biblical imagery, which is brandished like a talisman but doesn’t protect anyone. In the second act, the space is soaked with blood and other liquids, and the father is transformed into a giant reptilian puppet with snapping jaws (designed by Rachael Canning) who stalks his prey.

The girls’ late mother’s photograph takes a prominent place within Merve Yörük’s set design, flanked by Virgin Mary paraphernalia. We learn that she was both a victim of domestic violence and a freedom fighter, but she otherwise remains an enigma (though perhaps that’s the point).

It’s an arresting piece that isn’t afraid to go all-out, but a bit more deeper digging into the backstories of this troubled family would help to enhance our understanding of how these three damaged individuals have gotten to where they are.