Clarkston with Joe Locke West End review – lacking in scope but brimming with heart

The UK premiere of the Samuel D Hunter play continues until 22 November at the Trafalgar Theatre

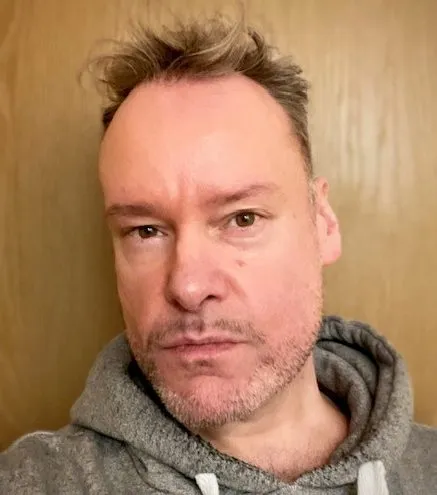

Heartstopper star Joe Locke’s face is emblazoned large on the poster and all over the exterior of the theatre, but fans coming to see Clarkston may be surprised that it’s not really a star vehicle. Samuel D Hunter’s decade-old play is a tender, downbeat duet for a pair of dispossessed souls with jagged interruptions by a third character, and Locke has, arguably, the least showy of the three roles.

Locke plays fragile Jake, newly relocated from affluent Connecticut to the backwoods town of Clarkston, and starting work as a Costco night shift shelf stocker, a job to which he is eminently ill-suited. Jake is on the run from himself: he has been diagnosed with the neurodegenerative Huntington’s disease, which will prematurely end his life (“my body is gonna forget how to be alive”). Furthermore, he leaves behind a failed gay relationship, and a degree in post-colonial gender studies (“that’s like – a thing you can study?” asks co-worker Chris incredulously). Locke acutely captures the nuances of somebody whose insecurities and issues mean that he’s never really considered how privileged he is. He’s nerdy, likeable, but intriguingly ambiguous: is he calculated or clueless, or a bit of both?

Locke is excellent, but it’s Ruaridh Mollica’s watchful, quietly tortured Chris that feels like the heartbeat of the play. That’s partly because, as Jake’s work colleague and the son of Sophie Melville’s recovering addict waitress, he’s the common ground between the other two characters. But more than that, Mollica draws the contrasting strands of Chris’s hardscrabble life with outstanding delicacy and a quiet, devastating magnetism. He’s an aspiring writer stuck in a dead-end job, repeatedly let down by a mother who barely accepts the sexuality he keeps hidden from the rest of this unsophisticated town; he’s kind but lowkey desperate, and Mollica delivers a hauntingly impressive West End debut.

Melville is brilliant and multi-layered as needy, unreliable Trisha, making vivid her maternal love for the son she barely understands, but absolutely chilling when cornered whilst in addiction’s grip.

The writing is subtle but blistering: a morose yet eloquent meditation on lives not well lived, with precious little hope, but an abundance of challenges. It’s blunt and bleak, and almost nothing happens, but the acting and the oblique humour ensure that it is engaging for the most part.

Hunter’s people are the losers in life‘s lottery, eking out their existences on the fringes of society, observers of, rather than participants in, the great American Dream. They’re drawn with clear-eyed affection and zero judgement, and while their horizons are narrow, Hunter plugs them into a bigger picture (Jake is a descendant of American frontiersman William Clark, for whom the Washington/Idaho border town of the play’s setting and title is named, and Chris is applying to study writing at grad school). The dialogue is terse, spare, filled with the stutters, slurs and non sequiturs of real-life speech; it’s defiantly unpoetic, but unerringly truthful.

The individual scenes in director Jack Serio’s production are played entirely naturalistically, but the overall style of the staging is expressionistic, with an ominous thrumming underscore and a stunning lighting design by Stacey Derosier that sometimes has the actors wading through an orange-tinged gloom before washing the entire playing area in a lurid acid yellow. The tension between presentation and material is interesting, but having audience members on stage is a needless distraction calculated more to fill the space than to make any dramatic point.

Steeped in dysfunction and human isolation, Clarkston is the sort of play – miniature of stature and scope but huge of bruised heart – that would have been tremendously powerful in the tiny second studio of the Trafalgar Theatre’s previous incarnation. Here, it feels a little overstretched despite the quality of the writing and performances, and the close proximity of a portion of the audience. Still, it’s a creditable British debut for Hunter, and admirers of Locke will be happy, while Mollica is likely to garner a whole new fanbase.