Reviews

Between Riverside and Crazy at Hampstead Theatre – review

The Pulitzer Prize-winning play comes to UK shores for the first time

Watching this London debut of Stephen Adly Guirgis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, it feels extraordinary that it has taken a decade for Between Riverside and Crazy to reach these shores. Michael Longhurst’s sizzling, thrillingly acted production for Hampstead ensures that it was well worth the wait.

Anybody who caught Guirgis’s earlier The Motherf***er in the Hat at the National in 2015, or his The Last Days of Judas Iscariot at the Almeida or Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train at the Donmar, will have an idea of what to expect here. Guirgis loves the flawed people, the misfits, the addicts, the lost souls only just keeping it together, and he writes about them with clear-eyed compassion, zero judgement, having them express themselves in bold, muscular, rude language, blisteringly honest and brutally funny. He takes the way real people, particularly working class New Yorkers, express themselves and elevates that to a poetic level, slightly heightened for the stage, like a Tennessee Williams of the Empire State. The writing is frequently gorgeous, but it bears the unmistakable tang of authenticity.

Between Riverside And Crazy centres on widowed Black ex-cop Walter ‘Pops’ Washington, holed up in the Riverside Drive apartment he’s inhabited for over 35 years, battling greedy landlords, and the NYPD who want to settle his lawsuit regarding a shooting from another cop which he claims was racially motivated and has left him physically compromised. Pops drinks too much and his rent-controlled dwelling has become a haven for the flotsam and jetsam of humanity, including his petty criminal son Junior, newly released from jail, Junior’s flaky girlfriend, and a recovering addict acquaintance who is now evangelical about his newfound healthy lifestyle. It’s a gritty but richly comic set-up, and though these characters are frequently operating on the most outward boundaries of human existence and indeed legality, they are great company.

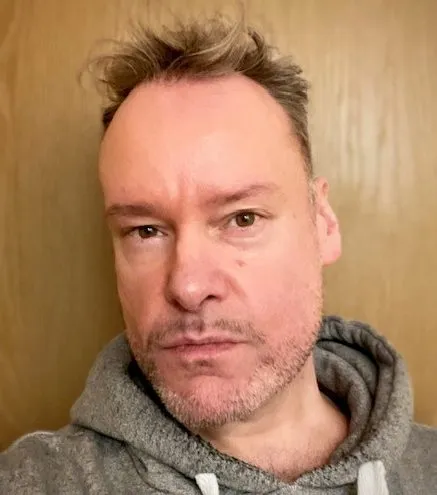

Following on from his magnificent Lear for the Almeida earlier this year, Danny Sapani now embodies another grizzled, volatile father figure trying to exert his authority while simultaneously abjuring responsibility. His Pop is a glorious creation, quick-witted, charming, maddening and not always as honest as he’d have you believe; it’s pretty hard not to love him even when he’s behaving appallingly. If Sapani’s accent sometimes wavers, his roaring, dissolute focus never does. Martins Imhangbe entirely convinces as Junior, the son torn between a life of petty crime and a genuine desire to do the right thing. Tiffany Gray makes a terrific professional theatre debut as his impetuous, street-smart girlfriend, and Sebastian Orozco delivers a nuanced, funny but unsettling performance as a fragile loose cannon not as free of his addictions as he thinks he is.

Judith Roddy makes something exquisitely tender but hard-edged out of a former colleague of Pop caught in the crossfire between him and her Police Detective fiancé (Daniel LaPaine, compellingly firing on all cylinders) who just wants to get the lawsuit sorted. You understand her frustration but also feel her deep affection, and you can’t miss his exasperation. If Ayesha Antoine’s fiery, hilarious Brazilian Church Lady, apparently determined to “save” Pops at whatever cost, seems to have wandered in from an entirely different play, it’s still a fabulous performance, with a surprising emotional pay-off.

Longhurst and his creative team, but perhaps especially sound designer and composer Richard Hammarton, have accurately recreated the pressure cooker environment of New York, its energy and edge, and the simultaneous sense of sentimentality and danger that pervades that most dynamic of cities. Max Jones’ slightly cumbersome set gets moved around unnecessarily in act two, dissipating the flow and causing problematic sight lines, and the actors aren’t always fully audible, but these are minor quibbles in an evening that’s consistently enjoyable, and frequently riveting.

A mostly naturalistic first half gives way to elements of magic realism in the second half, so that there are moments where you find yourself wondering if what you’re watching is to be taken at face value. That’s especially true of the quizzical, bittersweet ending which, at least in this staging, feels open to quite wide interpretation.

Ultimately, Between Riverside and Crazy is about redemption, and how hard it can be to break the cycles of bad behaviour that pass down through generations. It’s a warm, intriguing play, as wise as it is outrageous, as funny as it is grim, and in this UK premiere, it looks like a modern American classic.