4.48 Psychosis review – a profoundly impactful and important return

The 25th anniversary production of Sarah Kane’s final play, reuniting the original cast, runs at the Royal Court until 5 July 2025 before transferring to the Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon until 27 July

In June, 25 years ago, three actors in their twenties performed Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis in the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs. The playwright, a blazing talent, had taken her own life 18 months before, not long after writing this final piece.

Now the same three actors – Daniel Evans, Jo McInnes, and Madeleine Potter – and the same creative team return to the same space to perform the play once more. It has lost none of its power, but the passing of time makes it sing differently now. In a quarter of a century, we have learnt more about depression and mental illness; we talk more about it.

But Kane’s unique ability was to offer a description from the frontline, accurately to record the drain of despair, the siren call of suicide as an answer to the unbearable pain of living. In words that fall across the pages of the play like a poem, she heroically needles away at the balance point between life and death.

The tension is always there. Three early passages run like this: “At 4.48/when desperation visits/I shall hang myself to the sound of my lover’s breathing.”

“I do not want to die”

“I have become so depressed by the fact of my mortality that I have decided to commit suicide.”

As the play has established itself as a classic, studied in schools, produced around the world, each director and cast have to decide how to speak it: it can be performed as a monologue or with multiple actors taking on the roles of patients, doctors, and counsellors that emerge. Yet director James Macdonald’s choice to use three actors and divide the lines between them feels the perfect one.

The play is threaded through with trios – “Victim. Perpetrator. Bystander”, “Dr This and Dr That and Dr Whatsit”, “To be forgiven. To be loved. To be free.” – and the way the lines ripple through the cast leans into its essential lyricism, the musicality that underpins its radical structure.

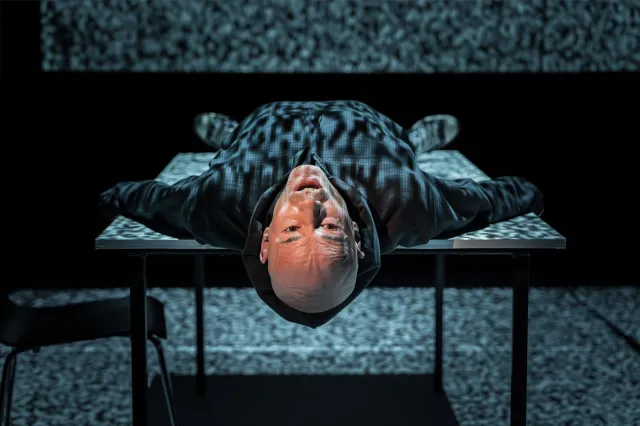

The effect is magnified by Nigel Edwards’ lighting, which switches sharply, and without warning, between midnight blues and queasy yellows to bright searching white, and a fuzz of static that is like the visual equivalent of white noise. Jeremy Herbert’s design sets a mirror over the stage; the sense of dissociation between mind and body that Kane describes is enacted in front of us. The quality of the actors embodying a state is emphasised as they sit, lie, or stand, the beauty of their frozen poses reflected, the emotions that pass across their face clearly visible. The projections bring in glimpses of an outside world, passing over them, unheeded.

It is extraordinarily beautiful, but the clarity of Macdonald’s approach also honours Kane’s own precision. There is nothing woolly about this writing. It is pin-sharp, angry, funny, as well as unbelievably sad. In one of the play’s most famous passages, the speaker describes their plan to take an overdose, slash their wrists, hang themselves. “It couldn’t possibly be misconstrued as a cry for help.”

That’s the terrifying, indelible thing about the play as a whole. Irrepressibly melancholy though it is to watch it, knowing that Kane did indeed kill herself at the age of 28, this is art, not life. It is her scrupulous, brave use of theatrical form to convey the unconveyable, to dig as deep as she possibly can into the pit of an illness that overwhelmed her, that makes 4.48 Psychosis such an important work. It’s not a cry for help but an attempt to explain, a profound examination of human need.

The acting is intense, spare, and watchful. Every line has meaning, every movement has intent. It is an overwhelming experience. At the close, the actors open the windows of the space and let in light and sound. Sitting there, quietly, reluctant to move, feels like an act of remembrance – but also an acknowledgement of the power of words to help us understand.