Matt Trueman: What could theatre learn from #HOFEST?

Hofesh Shechter’s festival provides a chance to get the measure of him as an artist. Matt Trueman asks if theatre could benefit from adapting a similar model?

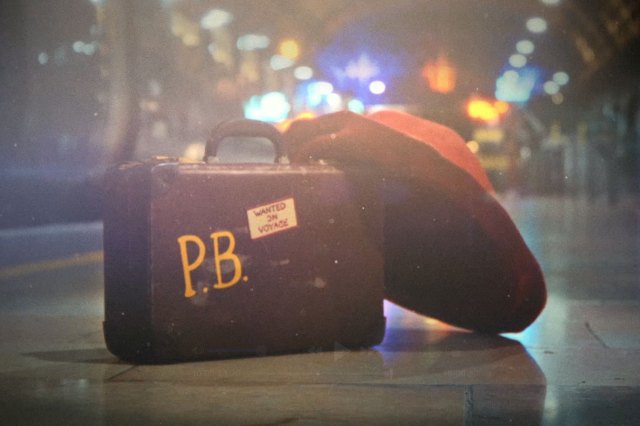

© Victor Frankowski

In the recent weeks, I’ve seen more of Hofesh Shechter than I have my own family. The Israeli choreographer, an artist with a cult following, has just produced a three-week festival of work, #HOFEST, across a number of venues in London – a really interesting model and one theatre might do well to borrow.

Having never seen Shechter’s work before, #HOFEST was a crash course in the choreographer. A Shechter lecture, if you like: four shows running almost concurrently.

The Royal Opera House hosted his first opera, a new staging of Christoph Gluck’s Orphee and Eurydice, with a chorus of dancers tumbling over the stage during orchestral sections. At Sadler’s Wells, there was contemporary dance proper: a remount of his wilfully gauche, gleefully self-indulgent triptych Barbarians. I missed the Shechter Junior company at Stratford Circus, but finished up with the grungey roar of Political Mother – a piece about the lure and danger of dictators – at the iconic rock venue Brixton Academy.

These are very different pieces – indeed, very different art-forms and very different contexts – but they have the same heart: Hofesh himself. Watching work in such close proximity provides a chance to get the measure of an artist. You spot recurrences. You pick up on patterns. You start to understand the style and the underlying purpose.

Hofesh’s work is explosive and exhilarating, full of jump-cuts, gear-shifts and handbrake turns. All-out delirium skips into courtly Tudor square dances. Roaring rock snaps into string sections. (He was a drummer in a band and still composes himself.) He likes the look of an orchestra, making musicians visible, and can turn a chorus of dancers into a choppy sea of bodies, so that people move like clashing currents and individuals disappear into a molten crowd. He has a love of reckless, headless abandon – dancers like pilled-up ravers going full-pelt, dreadlocks whipping this way and that – and seems to pillage from paganism, so that ritual circles recur. Dancers often shout, so that bodies that move become people that speak.

Shechter has a bit of a cult following. (You have to to pack Brixton Academy out with 5000-odd people watching contemporary dance, right?) His work gets into your body and it helps that he has a strong personal style – so strong, in fact, that a number of dance critics more familiar with his work have asked when recurrences become regurgitation. His personal ‘brand’ has taken him into theatre – he movement directed Motortown at the Royal Court and will, next month, choreograph his first Broadway musical, a revival of Fiddler on the Roof – and recently ballet and opera. #HOFEST is, I suppose, an extension of that.

© Dan Wooller for WhatsOnStage

Might theatre embrace the same production model? If so, who would suit it? It could illuminate an artist’s work, particularly those with distinctive practices, working across a number of art-forms, contexts and countries. Imagine if Katie Mitchell hosted #MITCHFEST – a chance to catch up on work from overseas, to compare her opera with her performance lectures and her kids’ shows, her naturalism with her camera pieces, to return to Waves or Attempts on Her Life. Extended exposure to her work might reduce some of our resistance to it. Who else might benefit? Ramin Gray, maybe. Alecky Bylthe. Complicite. Kate Tempest. Even Mark Rylance – the perfect chance to resurrect Rooster Byron…

In theatre, it can take a long time for an artist to build up that strong sense of artistic identity, and for an audience to get to grips with an artist’s work. Playwrights rarely have more than two plays a year (Simon ‘Shire Horse’ Stephens excepted) and directors can’t do more than three or four, particularly not as primary artists. Companies like Complicite or 1927 end up touring a show for years, so new work comes around even slower.

Revivals of recent work are rare in British theatre. Remounts are even rarer. Generally, then, if you miss the first outing, there’s no catching up. Without following a particular theatremaker slavishly over years, it’s pretty hard to get the measure of them and, once you have, you’ll still end up with big gaps – all those early shows you missed.

By contrast, think of a visual arts exhibition in a gallery: the Martin Creed show at the Hayward, for example, or Ai Weiwei at the Royal Academy. You get a whole survey of an artist’s work laid out in a set of rooms, a guided tour through their career, carefully curated and juxtaposed to give a good sense of the artist’s identity, interests and obsessions.

It’s rare to find anything comparable in theatre. Playwrights, occasionally, as with Sheffield Crucible’s seasons dedicated to David Hare, Brian Friel and Sarah Kane. Forced Entertainment and Chris Goode have both held retrospectives and, much like #HOFEST, both provided a fascinating insight into his body of work and a great chance to catch up. There’s something of it, I suppose, in the West End seasons run by Kenneth Branagh, Michael Grandage and Jamie Lloyd, but even there, it’s spread out over a long stint of time.

The difficulty is that theatre can be more costly than dance. You often have sizeable sets, where dance might only need a space and, as such, can be lighter on its feet. Dance (and opera) runs can only last a week or two, theatre tends to run for four or more, making the festival model much more of a commitment and, indeed, a risk. It’s harder to get an old gang back together too, availability and, indeed, age can get in the way. More’s the pity.