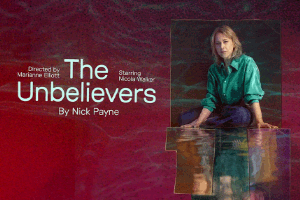

The Unbelievers with Nicola Walker at the Royal Court – review

Nick Payne’s world premiere play, directed by Marianne Elliott, runs at Jerwood Theatre Downstairs until 29 November

The unwillingness, or inability, of a mother to move on when her child goes missing, even after the best part of a decade, is studied in The Unbelievers, Nick Payne‘s new play – his first theatre work in six years – for the Royal Court. It’s an intermittently engrossing, well-acted and slickly staged look at loss, grief and how closure is impossible without answers. However, in presenting the inexplicable and unfathomable, Payne’s writing and Marianne Elliott’s production tend to be as elliptical and inconclusive as the subject matter.

Eschewing a linear timeframe, the scenes depicting Miriam (Nicola Walker) and her fractious relationships with her ex-husbands and remaining grown-up children are jumbled, sometimes confusingly, across a seven-year period, often bleeding into each other. As in earlier works such as Constellations and Elegy, Payne gets potent theatrical mileage out of putting tragedy cheek by jowl with a tart, biting wit, and few actors are as adept as Walker at suggesting anguish roiling away under a matter-of-fact surface.

That anguish does break through occasionally, notably in a sequence where her child Nancy (Alby Baldwin) has arranged a seance to try and contact missing brother Oscar, and Miriam is so wrong-footed that she ends up primal screaming underneath the table. If it’s not as moving or distressing as one suspects it should be, neither Walker nor Payne are overly interested in endearing Miriam to us. She’s frequently witty, but equally, she’s abrasive and mercurial, which is understandable given what she’s going through. Just occasionally, Payne has her express herself in language that threatens to sound like parody (“Pool. I feel like a pool…a pool of water”).

Paul Higgins and Martin Marquez offer sensitive, bleakly funny portraits of Miriam’s understandably bewildered ex-husbands, and Ella Lily Hyland and Baldwin are wonderfully natural and emotionally true as her contrasting children. The sense of a bunch of family members caring about each other very deeply, but unable to build bridges between themselves, is strongly felt. Isabel Adomakoh-Young and Jaz Singh Deol are vivid and amusing as a couple of all-at-sea professionals determined to help them.

Bunny Christie’s clinical set has most of the cast visible at all times, sitting around in what appears to be some sort of waiting room upstage from the main action of the play. It lends a chilly, institutionalised feel, in contrast to the more elaborate, expressionistic sound and lighting designs (Nicola T Chang and Jack Knowles, respectively). The tonal inconsistencies may be deliberate, but they make for a frustrating experience overall.

That inconsistency is typified by what is probably the evening’s most entertaining scene: an excruciating family party where daughter Margaret introduces Benjamin (Harry Kershaw), the uptight older man who’s the father of her unborn baby, while an acerbic Miriam mercilessly scores points against her ex’s new partner Lorraine (Lucy Thackeray), a blousy vulgarian who clearly means well but is like a fish out of water. It’s uproariously funny, especially when Miriam’s already fragile social facade cracks wide open due to sheer boredom, but feels like a completely different play from everything else. Kershaw and Thackeray are delightful, but broadly comic in a way that nobody else in the cast is playing.

Running at less than two hours without an interval, The Unbelievers takes a while to build up a head of theatrical steam; in terms of writing, structure and staging, it isn’t sufficiently focused to be really satisfying, and it ends with a moment of ham-fisted symbolism that feels like over-egging. Still, it’s never less than watchable and when it’s good, it’s very, very good, although seldom does it seem to have the complete measure of its complex, emotionally-charged subject matter.