Shed: Exploded View at the Royal Exchange – review

Phoebe Eclair-Powell’s 2019 Bruntwood Prize-winning play makes its way to the stage

Cornelia Parker’s art installation, “Cold Dark Matter: Exploded View” – the visual reference point for Phoebe Eclair-Powell’s new play – featured a constellation of shards, frozen in stasis, from a blown-up garden shed. This production doesn’t need it. The characters, here, are fragments orbiting a ground zero.

The couples are young and old: a uni student and her new boyfriend; their adult parents, left only with each other when she moves out; an older wife who’s increasingly the carer for her unravelling husband. Each of their trajectories is terminal, shattered by mounting incidents of domestic violence.

It’s a bitter, roiling play. Rage sparks out and effectively consumes it at the end. Director Atri Banerjee contains it without suffocating that fire, though it can still feel a little overly agitated; there are moments when you wish the aftershock of scenes’ confrontations, eruptions and fallouts burned longer before resetting for the next. Some of the monologues are also too abstract.

Its view is focused closely on victims rather than perpetrators. Incisive about the relationships domestic abuse destroys, and women’s attempts to shield each other from it, rather than the systems that lay the poison. There are no fathers and sons, or male friends, for instance, that might expand it into a fuller examination.

It’s a relatively clear-cut, straightforward, monochromatic view of a complex social issue: every man is aggressive and volatile with near-identical patterns of outbursts; every woman recoils and faces it off passively. The senile husband’s lashing out as a result of illness and confusion adds another dynamic but feels disconnected from that core. The men can also feel consequently weaker: more simplistic archetypes without all the nuance and paradoxes that make these relationships so complicated.

The mother and daughter relationships have the greatest impact. Eclair-Powell threads intergenerational parallels. A push in one timeline is repeated in another. A couple’s first marriage is witnessed by another in their third. There are direct echoes and crossover, with lines spoken simultaneously by different couples. We see different reactions to news of redundancy: the women sympathetic; the men coldly unsupportive.

Lizzy Watts and Hayley Carmichael are particularly strong as the mother and older wife. Watts’s harried mother finds ways to reach her daughter, always weighing up whether to intervene, literally taking her place at the end. Carmichael’s look of strain and dislocation shows how you can be in a relationship yet be totally alone if it’s dysfunctional.

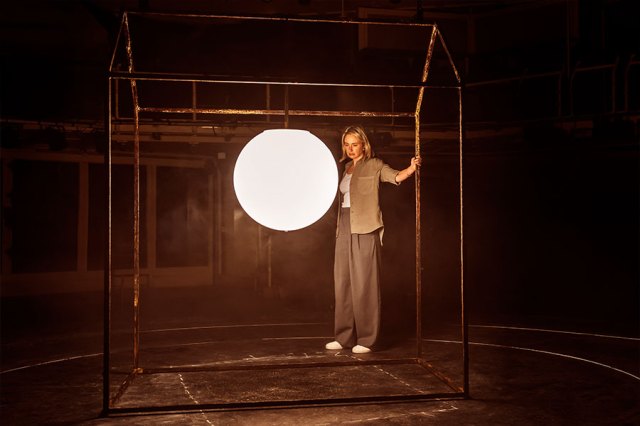

Naomi Dawson’s set consists almost entirely of a circular dark slate like a crater, revolving like a hurtling meteor. The cast chalks on slights, anguished questions and blunt commands – a swirling vortex, each another spark until it ignites. Costumes pick up smudges and traces – they can’t avoid bearing the imprint. The men’s expletives stick like shards of glass.

The shed is also the frame of a home, blown through. When Watts draws its outline on the floor, it resembles the plot of a grave. After it’s opened up at the start, its skeleton hangs over the action, in some way mirroring the defencelessness of the women below. As she tries to reassemble its panels, you realise she’s trying to build a fortress.

It’s a bracing confrontation with the doom loop society seems locked in. You look at the statistics: consistently higher proportions of women reporting domestic abuse. “Boys will be boys,” one character sighs. And round we go, like that stage. Round and round and round.