Sarah Crompton: Dance can't continue to function in a self-enclosed bubble

Sarah Crompton reflects on Liam Scarlett’s dismaying ”Frankenstein” and how the Royal Ballet should help to find effective ways of storytelling

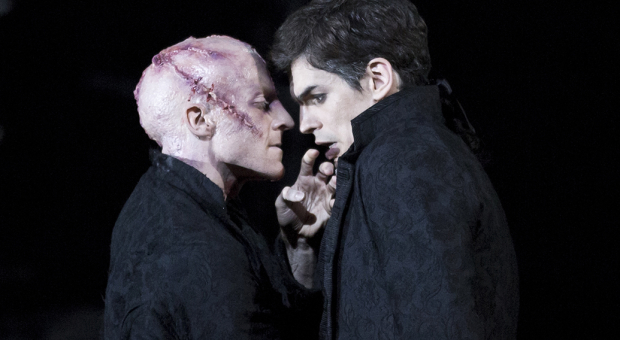

© Andrej Uspenski

It’s not often that a new ballet causes a heated public debate between critics, so Liam Scarlett‘s Frankenstein for the Royal Ballet is to be applauded for making passions run so high that arguments broke out, not just between the professionals but between audience members too.

Everyone thought the dancing was excellent. But critical reaction veered between four and one star. Cheering at the end was prolonged and the comments on Twitter excited; but many audience members were disappointed.

What’s interesting to me – and I came down on the negative side of the scales – is that if you look at what everyone was saying, rather than the stars awarded, views were remarkably close. Scarlett is a gifted choreographer, with some great ideas. But – apart from the final scenes when you suddenly glimpsed the dramatic power of the story – he struggled to find a narrative line through Mary Shelley’s gothic tale and, crucially, to depict the tortured relationship between Frankenstein and his Creature.

Our leading ballet company should not allow a talented young choreographer to flounder

If you are going to transform the story into a dance work, you have to find a way to express all that and make audiences feel that the steps speak as loudly as words ever could. In the 21st century, when theatre boasts makers such as Robert Lepage, Peter Sellars, Simon McBurney and others too numerous to list, dance needs to have enough rigour to ask itself questions about why it is telling particular stories in specific ways. It can’t continue to function in a self-enclosed bubble.

This interplay between other forms of culture and dance often produce the most exciting results. When Kenneth Macmillan was making Mayerling, he commissioned a scenario from Gillian Freeman, an experienced script writer; the ballet benefited from her sense of structure. More recently Christopher Wheeldon asked Nicholas Hytner‘s advice about adapting The Winter’s Tale as a ballet and produced a triumphant version as a result. The director Nancy Meckler has forged an illuminating creative partnership with the choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa which led to a crystalline version of A Streetcar Named Desire.

What I found dismaying about Frankenstein – and the commissioning process at the Royal Ballet that allowed it to be premiered in its current form – is that no one had noticed its lack of a strong dramatic armature at an earlier stage. It was crying out for someone with different experience to come in and suggest ways of adapting the scenario to make it clear and powerful. Someone who had never seen ballet simply would not have understood why the minor characters got to dance such a lot while the key protagonists lurked in the shadows. Their basic questions would have been the right ones to ask.

If dance is to stake its claim to be an art form that speaks for today as well as one that reminds us of the past, it has to be brave enough to open its eyes and arms to effective ways of telling a story. And our leading ballet company should be at the forefront of that process, not allowing a talented young choreographer to flounder without enough support.