King Lear (NT Olivier)

Sam Mendes’ production of ”King Lear” starring Simon Russell Beale as the eponymous monarch opened at the NT Olivier last night

© Mark Douet

Lear’s kingdom, as designed by Anthony Ward, is a dark and cheerless Eastern European sort of place, with mottled blue walls and elemental panels, scudding clouds, a vast council chamber table, microphones, a huge granite statue of the great-coated king in a bleak town square, and an army of faceless supernumeraries.

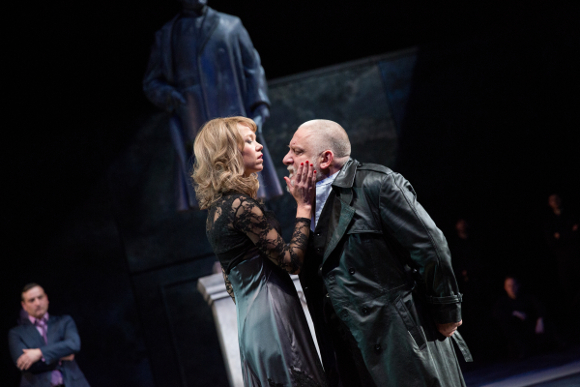

No wonder Simon Russell Beale‘s shaven-headed despot, head jutting forward like a dangerous snail’s from its shell, wants to divide the place up among his daughters. Yet with a cruciform platform extending into the stalls, where Adrian Scarborough‘s mirror image of a Fool sits quietly, mournfully through that first explosive scene, there’s intimacy, and poignancy, afoot, too.

There’s an ominous rumbling behind all this, not just the imminent storm on the heath, but a sense of geriatric foreboding. After cursing Kate Fleetwood‘s vampish and seductive Goneril, a Judith Anderson figure in swept-up hair and mauve velvet, Russell Beale beseeches no-one in particular, “Let me not be mad,” as though on the brink of an abyss that will swallow him.

He knows himself too well, this Lear, and fears most the loss of control, the slippage of his own rationality. After an out-of-control assault on the Fool in a hovel of tin lavatories (the joint stools) and a newly-delivered bath, still in its wrapping – a nightmare echo of Michael Gambon absent-mindedly smothering Antony Sher’s red-nosed clown at the RSC – Russell Beale dons the cap and feathers himself.

He switches completely, clicks into madness. His slow traipse towards the grave is that of a disorientated hospital patient (his piece of toasted cheese is a banana) in a medical gown, not sure of where he slept last night, drifting into a fuzzy gloaming with sudden, heart-breaking shafts of recognition – for Stephen Boxer‘s blood-boltered Gloucester and, eventually, Olivia Vinall‘s girl soldier Cordelia.

Because of the scale and space in the Olivier, you really do feel that everyone is on a journey in this play, and these are plotted by director Sam Mendes with elegant, intelligent precision: Anna Maxwell Martin‘s Regan goes from girlish sycophancy (earning a smack on her bottom from dad) to gruesome sadist in the terrifying blinding of Gloucester, to fur-clad power-drunk adulterer.

For this production charts not only the disintegration of the natural order, and public morality, but the death of a nation state, too. Sam Troughton‘s suited, bespectacled Edmund – voice happily restored after missing one-and-a half previews – is a sofa-bound political schemer sucked into physical action; while his true-hearted half-brother Edgar, wildly and mesmerizingly played by Tom Brooke, covered in grimy tattoos, fully exposed, nether bits dangling, wrings out all sentimentality.

This makes the greatest scene in the play – the encounter on Dover cliffs with his own blind father – all the more sensational; for “poor Tom” (aka Edgar) doesn’t really know who he is anymore, either, and pushing Gloucester to the edge is an act of unconscious villainy as well as reckless mercy. There was a time in our theatre when the leading actor always played Edgar; that parity of tragic status with Lear is restored in this production.

I’m surprised, though, that the Olivier drum, as well as the revolve, is not pressed into action. The promontory at Dover is a bit trite, and the semi-circles and straight lines of extras (at one point equipped with that old design cliché of black umbrellas) too rigid. But, otherwise, this is the most completely satisfying version of the play in a long while, full of piercing insights in the murk, not least from Stanley Townsend‘s powerful, superbly spoken Kent, rescued from boring dutifulness to run up a lone flag for public decency.