”From Here to Eternity” at Charing Cross Theatre – review

© Alex Brenner

I distinctly remember coming out of the epic original production of this sombre musical at the Shaftesbury Theatre back in 2013 and thinking that there might be a really good show locked somewhere inside the overblown grandeur of Tamara Harvey’s staging. This new version, directed by Brett Smock, who also helmed the 2016 American premiere, scales down everything except the volume (more on that in a moment) but still doesn’t make a great case for a revival. It provides a rousing, histrionic night in the theatre, but only intermittently manages to suggest why Tim Rice (lyrics), Stuart Brayson (music), Bill Oakes and Donald Rice (book) thought this story would make a decent musical.

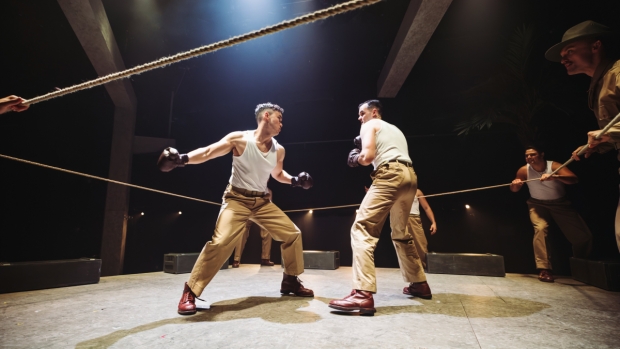

The problem may be the characters. The original James Jones novel, and subsequently Oakes and Rice’s script for the musical, pulls few punches in its depiction of the frustrations, sexual and otherwise, of a company of US soldiers training, in-fighting and generally trying not to lose their minds in the run-up to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour that would force America to enter the Second World War. Brutality, sexism and racism abound, and the idea of being outed as “queer” feels like the ultimate threat. In the midst of all this, the commanding officer’s wife is having an affair with his top aide, and a young infantryman who is also a talented boxer arrives, determined never to take to the ring again after blinding a former opponent.

It’s gritty, grown-up stuff, but, unlike in a novel, we don’t learn enough about the back stories and motivations to really invest in the people onstage. The script is workmanlike but not particularly illuminating, some of the acting a bit wooden, and when the principals express themselves in song, the decibel level is so high that it’s hard to decipher what they’re actually singing about.

As a result, they remain remote, indistinct stock figures, despite the hard-working cast. There’s the coldly ambitious Captain (a glowering Alan Turkington), his resentful but sensuous wife (Carley Stenson, superb), her stiffly dutiful lover (Adam Rhys-Charles), a cheeky chappie Private with a gay double life (Jonny Amies), a couple of company bullies, a pragmatic prostitute who gets the best number (impressive newcomer Desmonda Cathabel almost stops the second act with the gorgeously rueful ballad “Run Away Joe”) and her amoral, tough-talking madam (Eve Polycarpou chewing the scenery with real aplomb). Jonathon Bentley gives the haunted, decent Prewitt a credible, tormented otherness, and a stratospheric belt of a singing voice. They’re all recognisable “types”, put over mostly with conviction and skill, but seldom sympathetic or even interesting enough to connect with.

Stuart Brayson can certainly craft a catchy tune and the score works best when the music turns bluesy or anthemic, although it’s more reminiscent of the gargantuan pop operas of the 1980s and 1990s than evocative of the 1940s when the show is actually set. Nick Barstow’s boisterous orchestrations hurl everything at the wall, from ukulele to slide guitar to brass to harmonica, but sometimes make the music sound almost indecently jolly in comparison to the grim stories being told. All of the singing is utterly glorious but amplified to such an extent that some of the big choral numbers come close to causing actual physical discomfort instead of the exhilaration they’re presumably aiming for.

Stewart J Charlesworth’s palm-framed set places the audience at either end which makes for striking stage pictures when the whole company are present (the opening and closing ten minutes are authentically thrilling) but is incompatible with the ‘park and bark’ requirements of much of the score. Singers are constantly being forced to wander about in moments of high emotion so that both sides of the house get at least some face time: egalitarian it may be, but it’s distracting and robs several ballads of their power. Adam King’s highly atmospheric lighting and Cressida Carré’s macho choreography work well in a space that looks exciting but ends up requiring a wearisome amount of repetition in Smock’s occasionally clumsy staging.

When the attack on Pearl Harbour actually comes, it is staged with starkly blinding lighting, terrifying sound effects and lots of slo-mo anguish, while, simultaneously, the women of the cast deliver from above, and with real passion, the wistful, memorable anthem “The Boys of ‘41”. It’s a genuinely powerful, lump-in-your-throat moment in an evening that could use a few more of those. South Pacific this isn’t, but neither does it trivialise a troubling period in world history.

I’m not convinced From Here To Eternity really needed reviving, but audiences who miss Saigon and fancy a break from Les Mis but still want to be bombastically belted at, may well have a wonderful time.