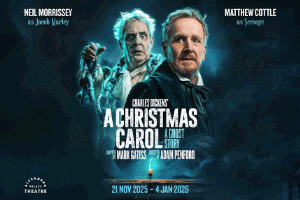

A Christmas Carol: A Ghost Story at Alexandra Palace Theatre – review

Mark Gatiss’ spooky adaptation of the Dickens classic returns with Matthew Cottle and Neil Morrissey

If Charles Dickens had ever imagined his ghost story, A Christmas Carol, to be unfolding inside a vast, gothic hall with smoke drifting across the rafters like cobwebs, Alexandra Palace would have been the exact location. It is, without question, the star of this production. The moment you enter, the airy expanse, the high ceilings and the architecture that hovers somewhere between cathedral and haunted house all signal the same thing: brace yourself.

The creative team takes full advantage of this environment with precision. Directed by Adam Penford, his staging leans into the darker, horror-infused threads of the novella that are often softened in more traditional adaptations. Here, the ghosts are genuinely unsettling. Ella Wahlström’s sound design is remarkable, at times almost overwhelming in its effectiveness. The jump scares are plentiful, and the low-frequency dread that pulses throughout the hall elicits involuntary physical reactions from the audience.

Phillip Gladwell’s lighting and Nina Dunn’s video design work seamlessly together, building a visual world that often resembles a BBC One supernatural miniseries. Bleak streets, falling snow and the washed-out greys of poverty give the impression that Dickensian London is not as distant from contemporary society as we might hope.

The smoke itself becomes part of the storytelling. If you sit toward the back, you see the entire hall slowly consumed by it. Look again, and it settles in the air like thick cobwebs, framing Matthew Cottle’s Scrooge as a Miss Havisham-esque relic, drifting through the remnants of his own desolation. Cottle is exceptional. An impeccably judged piece of casting, he embodies a curmudgeonly, tight-fisted figure with such delicately rendered misery that the audience can practically sense the penny pinching radiating from him.

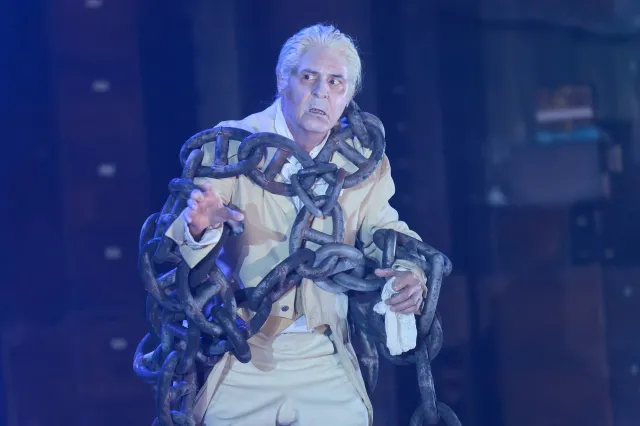

Neil Morrissey delivers a committed and atmospheric Jacob Marley, opening with real force and impressive presence, though his performance gradually settles into a quieter register than some of his previous work.

The ensemble, while clearly dedicated, doesn’t always land with the same impact across the board. Whether it is the natural constraints of Dickensian dialogue or some first-week stiffness, several performances feel a little wooden or predictable. Scenes in which Scrooge observes his past and present never quite lift off dramatically, and certain long passages lose momentum without offering much emotional payoff. There is also a slight lack of clarity in the ensemble work, with character roles occasionally blurring together, so it becomes difficult to track who is who or why particular figures are positioned where they are onstage.

The dancing is lively and genuinely enjoyable, but it sits alongside stretches that feel unenthused and anticlimactic. And while Paul Wills’s design is handsome, the production never fully uses the hall itself. This space begs for immersive staging, or at least for the ghosts to make themselves known from surprising angles. Instead, everything is kept fairly contained, which feels like a missed opportunity.

Whilst most of the costumes are generally effective (Wills and costume supervisor Heather Castle), every now and then, a coat wanders onstage that looks vaguely anachronistic. It breaks the illusion just enough to snap the audience out of the carefully crafted Dickensian London.

Still, the production excels in its technical achievements. The graphics are superb, the atmosphere is consistently strong, and Tingying Dong’s compositions deepen the sense of unease with subtle, textured underscoring. Castle’s costume supervision maintains cohesion even when the design choices stray.

A Christmas Carol offers a vividly atmospheric, visually striking retelling with an outstanding central performance and a venue that elevates the material immeasurably. Yet the production never entirely escapes the sense that its technical craft and architectural surroundings outshine the dramatic core, a reminder that Alexandra Palace doesn’t need a speaking role to dominate the storytelling.