”The Motive and the Cue” review – Jack Thorne’s National show delves into a Hamlet rehearsal room like no other

© Mark Douet

“Such a commanding advertisement for theatre, don’t you think?” Gielgud says. “Theatre as a trap. As an empathy hole into which huge bears can fall. I always find it very moving.”

It’s a marvellous scene, played with understanding and skill by the two actors. It also sums up the effect of The Motive and the Cue itself. It is a kind of mousetrap, a box within a box, which uses the art of theatre, and the story of a famous but troubled Broadway production that set box office records, to examine the art of acting and the nature of theatrical truth-telling.

Yet its real power lies in the way it takes the rehearsals of a classic play to hold the mirror up to nature and reveal wider insights into human nature and our desperate longing for affection, and applause. It’s a play full of compassion, funny, witty and utterly compelling.

Sam Mendes’s smooth and sophisticated direction takes a cinematic approach, with surtitles taking us through the process of rehearsal from Day One to First Night, each with an appropriate quotation from Hamlet. An aperture opens at different widths on Es Devlin’s fluid set, revealing a monochrome rehearsal room where the company gather in search of theatrical greatness, or the vivid red-walled hotel suite where Burton holds court, newly married to Elizabeth Taylor (Tuppence Middleton), her glamour as bright as the room.

© Mark Douet

Everything looks beautiful, with Jon Clark’s lighting carefully marking the passage of the days through a phalanx of long, grey windows, covered in blinds. But it also plays with the artifice and reality that is the subject of the piece itself; the entire structure is like a series of reveals, as tempers flare, personalities clash, and the nature of the play and of Burton’s view of it is finally uncovered.

Thorne has based his account on two books about the process by William Redfield (who was playing Guilderstern and who Luke Norris plays as an inquisitive, pushy hanger-on) and Richard L Sterne (who doesn’t appear). The events recounted are broadly true, but Thorne has carefully shaped them into an epic confrontation between “a classicist who wants to be modern and a modernist who wants to be classical”, as Taylor explains to Gielgud when they first meet, moving the focus from crowd scenes to monologues, from his text to Shakespeare’s, with great skill.

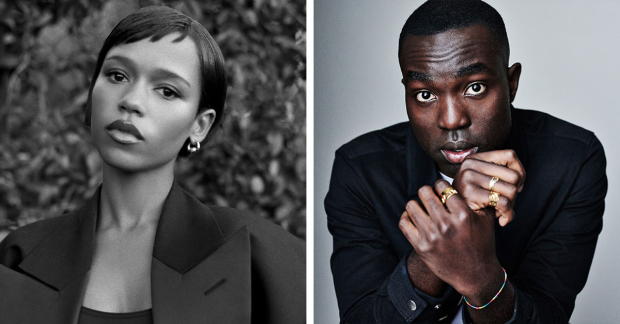

As Burton, Flynn has the almost impossible task of finding the unique quality of a man whose voice and looks made him the most famous actor in the world at the time. He catches the rasping bite and the insecurity of this miner’s son, already haunted by demons and drink, though he sometimes misses the melody that made Burton’s speech so distinctive. The scenes where he tries on different versions of Hamlet, running the famous words in different ways, are feats of actorly technique, but Flynn mines the emotion in the words and is utterly convincing in his moments of anger, fear and despair.

© Mark Douet

Middleton makes Taylor a warm and wise presence, uncomfortable at being side-lined, but happy to support her man. Their scenes together have a kind of light, a sense of the passion that brought crowds to stand outside the theatre just to gaze at their glory, but also an affection that is supremely moving.

But in the end, it is Gielgud’s play. Thorne gifts him most of the best lines, and Gatiss lands them perfectly. In his gently melancholy performance Gielgud becomes a tragic hero, a man who feels deeply but is incapable of revealing his feelings, a great actor who worries he has been forgotten, a man who dreads the ravages of age and loneliness. It’s around him that the empathy of this richly complex play centres.

Towards the close, Gielgud and Burton sit together once again alone on stage, trying to find “the motive and the cue” – the intellectual reason and the passion – that will unlock Burton’s interpretation of the part. They talk about their fathers and about theatre. “I don’t think there is any other art form in the world where minds meet so beautifully,” Gielgud says. “One thousand people, sat together in communion with what’s in front of them.”

This play is Thorne and Mendes’s own love letter to the stage, full of both intellect and passion, clever and profoundly moving.