”Othello” at the National Theatre – review

© Myah Jeffers

Clint Dyer’s sensational new production, starring Giles Terera, makes an impressive attempt at explaining why no-one at any point asks the right questions of the right people. It surrounds Othello and Desdemona (Rosy McEwen), a Black man and a white woman who love each other, with a hostile society – an omnipresent chorus intently watching every move, willing them to fail.

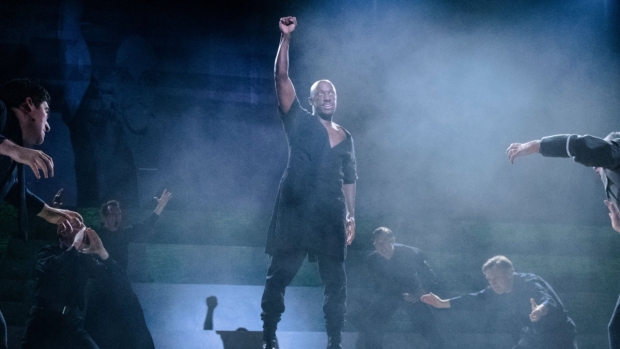

Dyer is the first Black director of the play in a major British theatre and the depth of his thinking about its meanings is clear in every scene. First, we see Othello the warrior, displaying his warlike prowess in the centre of Chloe Lamford’s monochrome stage, starkly lit by Jai Morjaria. Then we realise how quickly applause and gratitude can turn to disgust, as Paul Hilton’s black-shirted, Oswald Moseley lookalike, slyly eggs on the equivalent of a lynch mob, their bright brands burning to discover if Desdemona has indeed escaped her father’s house to marry her love and commit – in Shakespeare’s shocking phrase – “treason of the blood.”

The ferocity of the mob is contrasted with the couple’s love-struck dignity. There’s a moment when, in Lucie Pankhurst’s under-stated choreography, they seem to be holding themselves poised as if into a facing wind, ready to jointly retreat if things turn against them.

© Myah Jeffers

These early scenes, directed with immense confidence, set the pace and the tone of everything that follows, with the tension ratcheted up to breaking point as every moment passes. Details are carefully observed; the way the elders of Venice consistently ignore Othello’s outstretched hand; the way Cassio sneaks a drink even before Iago plies him with one; the moment when Iago expects Othello to hand him a badge of promotion and reacts when it does not appear.

This attention to nuance pays particular dividends when it comes to the women characters. This is a society riven not only by racism and fear of the outsider but by a hatred and distrust of women that means no-one believes them or listens when they speak. In McEwen’s sensitive, clever performance, Desdemona (dressed in a black jump suit) isn’t a victim but a heroine, fierce in her beliefs and her defence of her rights. As Othello begins to doubt her, her incomprehension fills her face even as she stands up to him; she goes to her death fighting.

Tanya Franks’ Emilia is equally finely-drawn. There’s no doubt that she is a battered wife, hiding her bruises under her hair, flinching when her husband Iago is near. Yet, like so many victims of coercive control, she is always anxious to please him. Only when she is alone with Desdemona does she seem to free to be herself. The scene where they both sit at the front of the stage and bemoan the behaviour of “these men” becomes one of the most moving and truthful in the play.

© Myah Jeffers

In this context, Hilton’s Iago isn’t just a man disappointed by a society that fails to reward him but a man so consumed with his own hatreds that he seems to have collapsed from the inside, swivelling around the stage with a terrifying, boneless energy. His malevolence isn’t motiveless; he hates his wife and believes Othello has seduced her. It eats him up and the chorus, leaning forward on the bleachers that surround the stage, egg him on, moving in sharp agreement to Pete Malikin and Benjamin Grant’s terrifying metallic soundscape.

Terera’s Othello makes the most of the contrasts of emotion that beset him. You sense his feeling of always being in peril, always clinging to a position that he is not sure belongs to him. When he declares his love for Desdemona, he literally dances and jumps, unable to contain his joy. His descent into doubt is just as extreme. He succumbs to the chaos his jealousy unleashes like a man who never believed he deserved anything better.

It’s an intense collapse, riding Shakespeare’s language to find his own meanings, an extraordinary performance at the heart of a revelatory and relevant production.