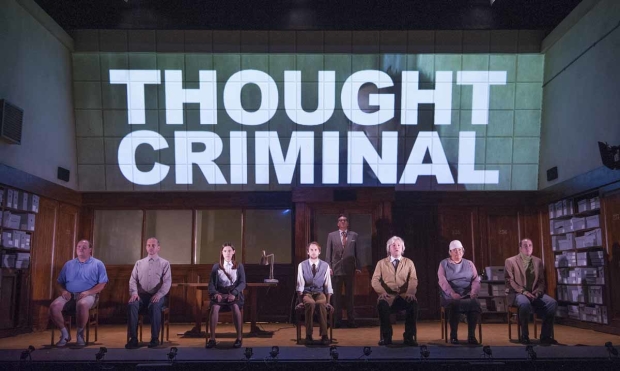

1984 (Playhouse Theatre)

© Manuel Harlan

Time shifts and jump cuts threaten to slice up the narrative of George Orwell’s dark postwar tale in Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan’s retelling, now back in the West End. In early scenes they trouble and wrongfoot us and allow this over-familiar nightmare, with its pessimistic and cynical glimpse of what was (in 1948) a scarcely imaginable future, to draw us in afresh.

The most startling quality of 1984, a year that’s now receded almost as far into the past as, for Orwell, it lay ahead, is its prescience. Today the unblinking eye of surveillance, whether through CCTV or in the GPS in our mobile phones, makes it hard to escape the unseen watchers; indeed, we embrace them via the magic of social media. At a time when millions plaster their most intimate thoughts on Facebook we’ve become part of the new totalitarianism without even noticing it. We’ve learnt to love Big Brother.

Matthew Spencer, new to the role of Winston Smith though not to the production, strikes a finely calibrated balance between anger, guilelessness and paranoia. His enervated restlessness and wide-eyed, half-glanced asides are electric. By contrast Tim Dutton’s bespectacled O’Brien is unchangingly urbane and a plausible friend to Winston even during acts of unspeakable torture.

From the world-weary opening narration by Stephen Fewell (who later becomes the ambiguous Charrington), Icke and Macmillan establish a tone of submissive exhaustion that never entirely goes away. The actor is helped by a subtle use of amplification; indeed, the sound design of Tom Gibbons is a player in itself. And there’s an undertone of John Le Carré to Chloe Lamford’s wood-panelled set: it evokes an enclosed, claustrophobic mini-England where no one’s to be trusted. Yet even this bland decor has its own chilling secrets.

What lifts this adaptation of 1984 above previous attempts to stage it is the combination of faithful storytelling and free-flying theatricality. There are gasp-out-loud moments here, and not only in the virtuosic scene change that takes us hurtling into the final horror. The little girl who spies on her parents is an incidental third-person character in the novel but here she is all too flesh-and-blood: a horrific brat, almost a real-life Chucky doll as played by seven-year-old Harriet Turnbull (one of three children who share this role). And her father, the splendidly supine Gavin Spokes, remains obscenely proud of her to the bitter end.

1984 runs at the Playhouse Theatre until 5 September