Michael Coveney: From Hackney Downs to Middlemarch highs and bad manners

There's nothing more tedious than critics going on about how much they're seeing or how much they enjoy what they do despite everything, blah-blah; similarly, the old critical stand-by of how much I was not looking forward to something but, blow me down with an ostrich feather, what a good time I had anyway, is another tattered rhetorical device way past its sell-by date.

So I shall try and stick to the plot, which is not myself, but the journey of a soul (admittedly my own) through masterpieces, which is how Anatole France defined criticism. You used to learn more than you wanted to know about Harold Hobson from his reviews in the Sunday Times, but the revelations were always about the higher life, not his bus timetable.

Then again, Hobson wasn't writing a blog. And I feel like resorting to both the above self-advertising tactics in reporting my experience on Friday night in the dark and cheerless interior of Hackney. After a twenty-minute ramble along unlit streets, my spirit sagging and my nerves fraying, I came upon the Hackney Downs Studios and a performance by the new Big House theatre company that reinvigorated my faith in "found" venues and lost causes, community action and post-Punchdrunk promenade theatre.

The studios have been going for a couple of years now, but I knew nothing about them. They're an unexpected enclave of warehouses and improvised huts for a whole series of activities on the site of a redundant print works. Here be jewellers, bicycle makers, architects, florists and all manner of designers, jugglers, peddlers and cake-makers. It's like a genteel Bartholomew Fair without the Puritan watchdogs and, hopefully, the pickpockets. And, in the corner, a marvellous bar and restaurant, serving delicious tapas, soups, main courses with funny names and cocktails.

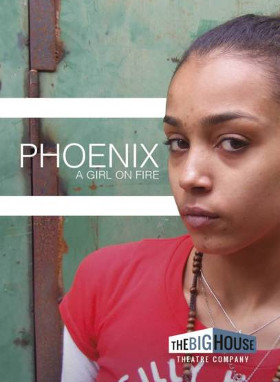

This was as unexpected a discovery as finding a needle in a haystack, a juice bar in a desert, or a memorable song in a new West End musical. And the new play, Phoenix by Andy Day, directed by Maggie Norris, takes the stories of various "disengaged" young people aged 16 to 25 and weaves them into a theatrical fable of disaffection, rebellion, aspiration and reunion.

Latitia is a young athlete whose legs are going "funny." Her dad's nowhere, her mum's a disturbed alcoholic. She makes a mess of her flat, falls out with her coach, falls in with a loutish boyfriend, and heads for the rubbish tip of social wastrels.

Norris has made a career of working with young people in prison and others (like this cast) coming out of care. The project is somehow to break the fall, or the transition, from one to the other (care-leaving to prison), and this method uses those stories to create a therapeutic, confessional theatrical event.

I've seen quite a lot of this sort of work with young people, but rarely anything so passionately or so brilliantly acted, and even more rarely so beautifully staged in a series of locations around a large warehouse: there's a running track on which we see slow motion sprint races and shrieking ensemble nightmares; a solitary tree, shedding leaves, in a local park; a cluttered rented bedroom full of detritus, dinginess and stains; a pile of tyres indicating a darkened hang-out for Latitia and her friends.

Latitia is the athlete who's drifting apart from everyone, including her brother, Jason (played by Kieran Nero, who really was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis eighteen months ago), and her peer group. There's a great scene where she goes to the doctor's receptionist and tries to make an appointment and is fobbed off: the receptionist, under pressure, screams the place down.

Everyone is trying to stay in one piece, hold it together, and it's this effort we all have to make, I guess – to a greater or lesser extent – that makes the play so moving. Latitia herself is played by an aggressively talented Jasmine Jobson who, in real life, owns up to having been "the most difficult child in Westminster" and a "hood rat" on the streets; she was taken away from her mother and placed in care by social services. This play, and this opportunity, is her life line.

Back in the more conventional theatre, the Middlemarch triptych at the Orange Tree is moving into its third chapter this week; I caught the second on Saturday afternoon, and it's absolutely outstanding. I also did my usual trick of lowering the average age of the audience by about ten years, so you can see that incoming artistic director Paul Miller (and Sam Walters, after forty years, is a very hard act to follow) might want to do something about that; I gather, incidentally, that there were seventy applicants for Sam's job and that Miller fought a very close-run contest right to the tape with Tom Littler and Philip Wilson.

I dashed from Richmond to a press preview of Jude Law's Henry V at the Noel Coward (reviews embargoed until Wednesday) and paid the price for sitting with a paying audience of "real" people: my neighbour had her phone on for most of the second act and munched her way through crisps and a whole box of Maltesers from Southampton docks to the Battle of Agincourt.

When did people start to behave so disgustingly in public places? Probably when they were told to stop smoking in theatres (the last one I remember you could smoke in was the Victoria Palace) or not compelled to stand up for the National Anthem at the Haymarket. Personally, I blame the government, the schools and the parents. Manners maketh a man, no manners mar him.

I suppose people paying a lot of money (best seats are £85) think they can do what they like. This wretched woman trudged out – and she didn't even look like a slob, or a theatre critic – leaving all her rubbish on the floor. I'm surprised managements and theatre owners, not usually slow to burden the paying customer with hidden extras like booking and restoration fees, don't instigate a policy of on-the-spot litterbug and noisy eating fines.