”Charlotte and Theodore” at Ustinov Studio review – a gentle exploration of hot topics

© Alastair Muir

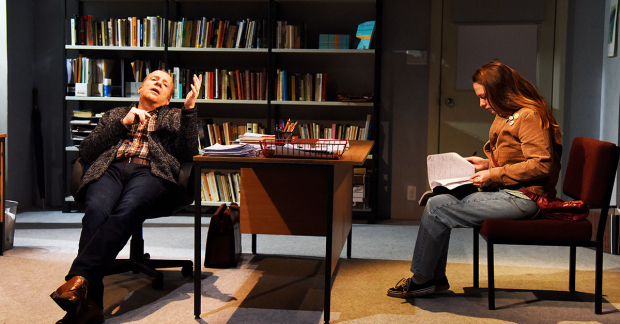

This can be seen as a wise move, there is a charm to the piece that allows us to like the characters rather than find them problematic as one might in say David Mamet’s fiery Oleanna, also seen recently in Bath. Lotty (Eve Ponsonby) and Teddy (Kris Marshall of Love Actually, My Family and Death in Paradise fame) are two academic philosophers; first work colleagues, then lovers, then rivals of a kind, bringing up children while juggling a new world order that has shifted power dynamics. It’s Lotty who is destined to have the career and Teddy who flounders now the face doesn’t fit.

We start at the end, a goodbye, and then jump back a decade to see how the relationship between them forms and contracts, as Marshall’s Teddy begins as a cocksure young philosopher with a fast track to the top, before he finds his star eclipsed as Lotty becomes the figurehead of the department and fast-tracked into the world of think tank groups, international travel, and high salaries.

© Alastair Muir

Craig’s play is a bit of a slow burn, not helped by a slightly old-fashioned production by Terry Johnson, that see the actors change costume on stage in blackout while piano music tinkers in the background, but its late scenes begin to really rev up. As Lotty reveals she has been offered a new job overseas, all the resentments, sacrifices and anger build to the surface in a scene that finally pops rather than smooths over. It’s unclear if Craig falls on either side of the debate, but he shows clearly that all must sacrifice something for this new world. Its last scene, the coda – swinging us back to the moment colleagues turn to lovers – gains new resonance as we see the way the landscape changed beyond what they initially comprehend.

Marshall, known for his range of man-child roles, essays another one here. There is something quite pompous in this academic philosopher, a man who consistently crosses his long legs when leaning against tables, marking his territory unsubtly. Ponsonby overdoes her early young enthusiasm but convinces herself as a woman having to make sacrifices as a mother and wife as her career builds. Her weary look as she realises that she no longer knows what is happening in the day-to-day life of her children cuts to the heart and the power in her voice as she calls Teddy out on his irrelevance, is astonishing. She wields her words like a blade that has been hidden for too long. She rises as Teddy shrinks.

There feels a neutrality to Craig’s play, a caution to land on any side. This probably makes sense as, after all, there are complexities to the current world that the play seems intent on exploring. However, it means the work can sometimes drift rather than land. The Bath audience on press night laughed at the idea of pronoun sharing, a generational thing maybe, that shows that there are still more discussions and understanding to be had as the world shifts, a point Craig’s play pertinently shows us.