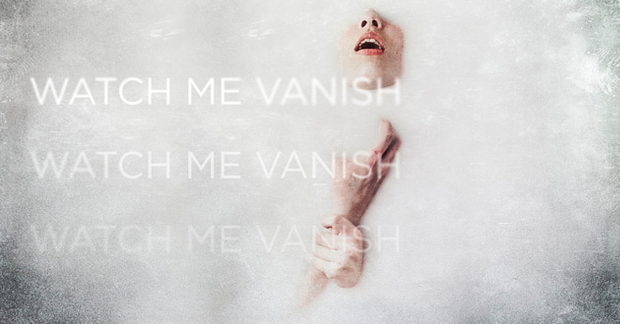

Holly Williams: How do you review a suicide note?

Our critic discusses the ‘lurid fascination’ with women who kill themselves and Kane’s ”4.48 Psychosis”

How do you review a suicide note? This was the question asked at the premiere of Sarah Kane's final play, 4.48 Psychosis, at the Royal Court in 2000 – most famously in Michael Billington's oft-cited review. With a new opera version about to open, this question is no less troubling today.

Sarah Kane wrote five plays, including her game-changing debut, Blasted which ripped apart the stage, and our expectations of theatre. Kane also killed herself in February 1999.

But you probably already knew that. Because she has become as famous for her death as for her work. And it seems to colour the way we approach the plays: reviewing the recent production of Cleansed at the National Theatre, a vision of institutional torture that's hardly autobiographical, most critics mentioned her suicide. Others on Twitter expressed their dismay at this.

And it does seem deeply unfair: to interpret her work through the filter of her biography is to deny it its own agency. Her plays are limited by being framed as the work of a suicidal woman, as if they're clues to a tragic death rather than works of art.

I mentioned her gender there, deliberately – because we seem to have an especially lurid fascination with women who kill themselves. And when it comes to myths about 'mad' women, tormented female artists from Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath to Francesca Woodman and Amy Winehouse, their tragic demise often threatens to overwhelm their artistic output. Presenting Kane's work this way not only risks turning her into mawkish theatre legend, but also diminishes the available readings of her experimental, funny, nasty, beautiful, political writing. This is to be resisted.

But then… there's 4.48 Psychosis. Which is actually about depression. Without assigned characters or stage directions, it's a polyphonic poem of self-loathing and desperate love, and a blackly comic satire on how the medical profession treats – or fails to treat – mental health issues. And it moves inexorably towards suicide.

Clearly, it would be hard to respond to this without acknowledging that Kane killed herself. Even her brother Simon, who at the time railed against the idea of 4.48 Psychosis being read merely as a suicide note, today acknowledges that she was writing about "what it feels like to be suicidally depressed".

For the critic, the show is challenging. How do you pass judgement on something that is still so red raw? And even if we try to resist the biographical reading, knowledge can do strange things to your critical capacity. The play seems authenticated by knowing it's 'real': how can you pull apart a document of such painful lived experience? The fear is that criticism becomes speaking ill…

But should art get a free pass because it's coupled with tragedy? Or should critics still sharpen their pencils? They have done so in the past; Dominic Cavendish has written of the "cloying over-reverence" for her work, while Aleks Sierz has pointed out the "adolescent petulance" of some of 4.48 Psychosis. Re-reading it, there are lines that struck my heart – and others that made me cringe. We best serve the work by being honest about this – and surely Kane would have hated to be canonised.

Cheeringly, Royal Opera House composer Philip Venables has said he wanted to go back to the words, not the woman, in his new production. Which is welcome, because another problem with the notion of the play as a testament of lived-experience is that it may blind us to Kane's invention. 4.48 Psychosis is no vomited-up, unedited stream of consciousness; it's carefully crafted, composed. A play, not a scribbled note.

Perhaps turning it into an opera will allow us to hear Kane's words afresh. Perhaps, in song, 4.48 Psychosis will sound less like the voice of one troubled woman, and more like the artwork of an enduring talent.

4.48 Psychosis runs at the Lyric Hammersmith from 23 to 28 May.