Good Night, Oscar review – Sean Hayes is flawless in his West End debut

Hayes is reprising his Tony Award-winning performance at the Barbican Theatre until 21 September

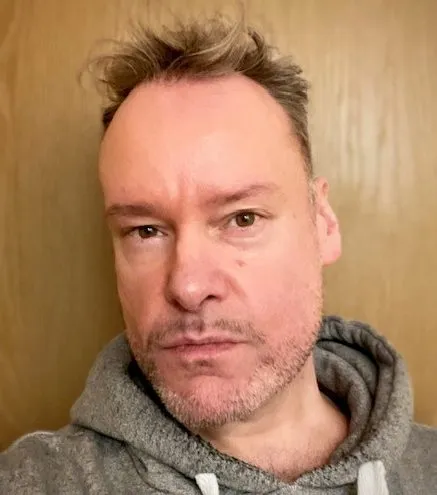

Anybody who only knows Sean Hayes from his beloved turn as sassy, über-gay Jack in long-running US sitcom Will & Grace (which, in fairness, is likely in this country to be most people) is in for a revelation when they see his Tony-winning performance in this Broadway import. He’s barely recognisable.

In Good Night, Oscar, Hayes is Oscar Levant, the American polymath whose skills encompassed acting, composing, presenting, and playing the piano at concert level. He was a notoriously complex character, prone to addiction, neuroses, violent outbursts, spending several spells in psychiatric hospitals, but also an esteemed, albeit controversial, fixture on the late night TV chat show circuit in the 1950s and 1960s.

Doug Wright’s play, running at a snappy, high-stakes, interval-free 100 minutes, is set in a Burbank TV studio where Levant is preparing to appear on The Tonight Show with Jack Paar, despite being in pretty poor shape. He’s been temporarily sprung by his wife June (Rosalie Craig) from the institution where she had him placed after a particularly nasty mental health episode that resulted in domestic violence (“first she drives me crazy, then she has me committed, it’s the perfect crime”). The studio boss (Richard Katz, raising wired apprehension to an art form) has severe misgivings, but Paar (Ben Rappaport, repeating his work from the 2023 New York production) is determined to forge ahead with Levant’s appearance.

Craig was also a recent special guest on the WhatsOnStage Podcast, which you can listen to for free here:

Throw in a star-struck young production runner way out of his depth (Eric Sirakian) and Daniel Adeosun as the psychiatric nurse present to keep an eye on Oscar and armed with a carry case full of potent prescription drugs, and you almost have the ingredients for a bad taste farce. That’s before we get to the interjections from deceased composer George Gershwin (David Burnett), who only Levant can see…

Wright’s script is very funny indeed, interpolating outrageous real-life quotes from Levant (“schizophrenia: it beats dining alone”, “underneath this flabby exterior is an enormous lack of character”), but also deals with the unscrupulous, exploitative nature of the entertainment industry. Oscar is not a well man, but even those who care about him are pushing for him to perform, and there’s a powerful sense of foreshadowing the sensationalist nature of present-day mass media.

Hayes inhabits his role so completely and with such detail that he’s equal parts mesmerising and painful to watch. He nails flawlessly the fluttering hands and slack-jawed terror of a person living on their very last nerve, the obsessive-compulsive tics that make sense to him but nobody else, the acidic wit as self-deprecating as it is mean (“I’m controversial, they either dislike me…or they hate me”). It’s a stunning performance that reaches its apotheosis in the production’s ultimate coup de theatre: like Levant, Hayes is an accomplished concert pianist and, at the show’s climax, he plays a driven, enthralling version of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody In Blue” that seems to represent Oscar channeling and exorcising all his demons at once.

All of the acting is first-rate. Craig’s innate likability has seldom been employed as advantageously as it is here, and she beautifully conveys June’s conflicted feelings about her exasperating husband. Rappaport’s masterful Paar is an oil-smooth provocateur with a genuine warmth for his deeply troubled guest.

Lisa Peterson’s terrific staging, which originated at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre before transferring to Broadway, is cinematically slick but well alive to the roiling distress under the text’s wisecracking exterior. Rachel Hauck’s gleaming TV studio set conjures up a glossy lost America before beginning to unsettlingly resemble a giant padded cell, while the sound design by André Pluess, distorting and expanding, takes us into Oscar’s mind as his medicated mania takes hold.

Inevitably, Good Night, Oscar won’t resonate with British audiences as keenly as with their American counterparts, and the imagined altercations between Levant and Gershwin rather outstay their welcome, but this remains a waspish, compulsive, meticulously well-crafted piece of theatre. Hayes’s brilliance elevates it into a must-see.