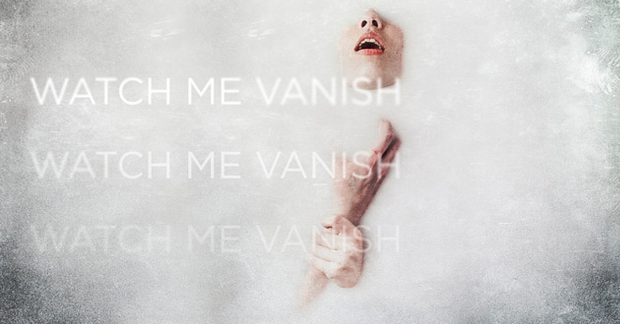

Review: 4.48 Psychosis (Lyric Hammersmith)

© Stephen Cummiskey

A playwright's suicide note or just close-to-the-bone drama? Either way, 4.48 Psychosis (the title alludes to the time of day at which the narrator achieves mental clarity, in her case a state of grace) is a bold theatrical poem and the most shattering depiction of mental illness yet to reach the stage. As a free text it can be played without character attribution by any number of actors, but in constructing his operatic version Philip Venables has opted for six female voices.

The composer's setting of Sarah Kane's text was garlanded with praise when it first appeared two years ago, and now the Royal Opera has revived it – something it rarely does with new commissions other than big beasts like Written on Skin and Anna Nicole – with the same creative team and three of the original cast members. The outcome of their collective effort is a work of fire and fury.

Hannah Clark's antiseptic white stage, a room with three doors, accommodates a doctor (Lucy Schaufer), her patient (Gweneth-Ann Rand) and four voices in the latter's head who are sometimes alter egos, more often mental antagonists. These are sung by Lucy Hall, Susanna Hurrell, Rachael Lloyd and Samantha Price. This sextet of first-rank artists serves the opera unswervingly in Ted Huffman's conspicuously underwrought production.

Breezy muzak greets the audience as it settles down, a sick-green wash of rictus aural jollity that drains our complacency before a note of real music is played. Once that happens, the stage becomes the playground for an astonishingly protean score that piles surprise on invention. Highlights: a sequence of whip-cracks like something snapping in the mind; spells of white noise that suggest mental shutdown; a long, folkish melody of deceptive beauty that's per-and sub-verted by high-lying arcs of dead string sound. This is Artaudian opera, from its aching passages of interlaced vocal harmonies to its blatant parody of church music. Venables displays an amazing technicolor palette of genuine individuality, nowhere more than in the striking confluence of amplified and natural voices, and he employs his colours unerringly to enhance Kane's drama.

Trouble is, music expands words to fill the bars available, and even with textual cuts 4.48 Psychosis is a long haul at 95 minutes considering it's essentially one long howl of despair. Early on the protagonist confesses "I hate myself", but it takes Kane a good while to deal with that realisation and Venables even longer. Of course, those three words alone are way too reductive of what this dramatic poem is about. "I will drown in dysphoria / In the cold black pit of myself" declares the suffering woman, and indeed the play's stream of consciousness is a dream of oblivion and the wakeful agony of finding it.

Huffman's staging doesn't entirely avoid workshoppy solutions. All six singers wear identical rehearsal-room garb and roam the stage to little purpose when not actively involved in a big moment; poor Rand has to hyperventilate while surrounded by physical manifestations of voices in her head… such ideas are a rite of passage for drama students but a bit low-rent here.

The musical thrills travel from Venables' mind to our startled ears via the dynamism of CHROMA under lithe-minded conductor Richard Baker. A small chamber ensemble with 25 per cent added saxophones, the group's star turns are percussionists Louise Goodwin and Sarah Hatch who sit high above the action and render the consultations between Schaufer and Rand on everything from metal blocks to wood saws (with bicycle-bell question marks). Projected text fills in the blanks. Gimmicky stuff, perhaps, but a welcome breath of wit in a dour opera.