Berlusconi review – manic melodies for a megalomaniac

A musical take on the politician opens in London

Let’s face it, any musical inspired by the antics of Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s infamous media mogul, property developer, corrupt politico and serial adulterer, was always likely to end up as either a ghastly farrago or a work of inspired brilliance. Ricky Simmonds and Simon Vaughan’s rumbustious piece confirms and confounds expectations by turning out to be both. This divine hot-mess of a tuner has an intelligence and invention that often engage the mind and thrill the blood, tempered with misbegotten moments of banality that should never have made it past the first day of rehearsal.

Luckily, there is more of the former than the latter, but it’s not always easy to work out who this is aimed at. Certainly not anybody specifically interested in Italian politics: there’s no information here that you couldn’t glean from Wikipedia. Nor does it tell us anything new about the seamy underbelly of power. From a political and dramaturgical point of view, this musical is unsophisticated to the point of idiocy. From a showbiz angle however, it’s dark, marvellous chaos, revelling in a flamboyant showbiz sensibility and subversive humour.

Musical theatre obsessive will have a field day spotting all the references and influences from other shows and styles: there’s the Fosse-esque hands springing through the floor, a transformation number reminiscent of Evita’s “Rainbow High” sequence, a musical argument recalling Rent’s “Tango Maureen”, a trio of female leads that could have come straight out of The Witches of Eastwick, the list goes on…

Simmonds and Vaughan use the framing device of having Berlusconi (Sebastien Torkia firing on all cylinders) retelling his astonishing but unedifying life story as a series of musical flashbacks, as distraction from the ruinous 2012 trial he faced for multiple counts of tax evasion and embezzlement. Silvio believes he’s creating grand opera starring himself, while his supporters and foes think they’re in a musical, and what actually emerges is a hybrid of the two, a through-sung vaudeville, where narrative and character development take second place to razzmatazz, stinging satire and occasional mawkishness, and where Jordan Li-Smith’s five piece band sounds grand.

The music recalls Andrew Lloyd Webber’s earlier work, when he was at his most edgy and exciting; this eclectic, bombastic score has more bangers and belters per act than most contemporary musicals manage across an entire evening. If there’s no strong overarching identity, it compounds its multifarious influences, from pounding electronica through soft rock and do-wop to patter songs and quasi-operatic grandeur, to agreeable effect. The singing is glorious, as are Li-Smith’s vocal arrangements. The cast album will be essential listening.

Journalist Mary Beard once likened Berlusconi’s womanising and tyranny to the Roman Emperor Tiberius and the show also intriguingly floats that idea, along with references to Napoleon and Jesus, but it all feels remains curiously under-explored in James Grieve’s frenetic, flashy production. Like Evita and Jesus Christ Superstar, the Lloyd Webber-Rice hits it frequently resembles, Berlusconi is more concerned with the cult of personality and the corrosive effects of power than providing any meaningful analysis of the man’s misdemeanours, downfall, and the unstable political legacy he left behind.

Simmonds and Vaughan seem to be warning that any politically inept, loud-mouthed lunatic can seize the reins of power anywhere in the world as long as they have enough money and chutzpah to dazzle the populace. This is hardly a lesson we need to be taught in the UK right now, but the point is reinforced nonetheless in an anthemic choral finale, pitched somewhere between rueful lament and call to arms, reminding us to be careful who we vote for.

The storytelling is hard to follow, the characterisations are sketchy at best, and it’s not always clear whether the audience should be laughing or taking what they’re watching at face value. Nothing about the production feels particularly Italian, aside from the flag waving opening number and the colours of ‘Il Tricolore’ bathing Lucy Osborne’s white marble-stepped set as we enter, but at least we are spared dodgy attempts at accents.

Still, there are some fabulous moments: a number where Emma Hatton’s gorgeously sung ex-wife criticises Berlusconi to assembled press while the man himself and his henchman (Matthew Woodyatt, excellent) prowl around turning off cameras and confiscating mics from disembodied hands, is breathtaking in its ambition and ingenuity. A tongue-in-cheek love song (the only one in the score actually) is hysterically funny, not just due to the leaping fish and seabirds that accompany it, but because it’s between Berlusconi and an increasingly exasperated, vodka-swilling Putin (hilarious Gavin Wilkinson). Many of the lyrics are sharp and incisive, although the sound design sometimes renders them unintelligible.

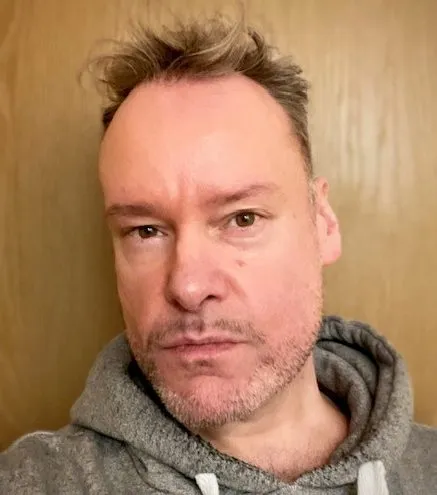

The imposing set, all staircases, platforms and multimedia screens looks suitably monumental although the lack of flat playing areas hampers Rebecca Howell’s sparky choreography, and the whole staging occasionally feels a little hemmed-in and rougher around the edges than it should be. The casting is superb throughout though. Sally Ann Triplett is a magnificently full-throated courtroom adversary to Berlusconi, Jenny Fitzpatrick brings charm, edge and a thrilling belt to a TV reporter, and Emma Hatton gets the best solo number, a shimmering, rueful aria “Secrets And Lies” which she performs with an exquisite restrained power. In the title role, Torkia is like a cartoon made flesh, with a terrific singing voice.

All in all, this needs a considerable amount of work to become as accomplished as several of the shows it’s so strongly reminiscent of, but it is still refreshing to encounter a bold new musical with brains, brawn, unashamed theatricality and packed with good tunes. Deliberately cynical and manipulative (like the titular character himself), it’s also deliciously campy, and has definite cult hit possibilities.