Julius Caesar (West End)

Doran’s setting, in an unnamed African country, captures the febrile mood of a nation as it veers between democracy and autocracy. Designer Michael Vale has put Caesar’s statue at the heart of the set, a reminder that he’s the overwhelming personality of the age. And the statue’s destruction in the second half acts as a reminder of how fragile that power is.

There are two aspects in particular that really stand out: the sing-song delivery of the actors accentuates the verse, and the crowd scenes are superbly handled.

The African accents work superbly; the text sounds vivid as if it were a living language. There’s plenty of life in the mob scenes too. Julius Caesar is a Shakespeare play that really involves the ensemble, and the crowd scenes are a vital part of the action. Doran’s handling of them is exemplary; by utilising a call-and-response mechanism, they become almost religious in fervour.

And the soothsayer’s presence is neatly handled too. A shaman-like figure, he watches the proceedings balefully, helping Antony with the funeral rites.

The interval (which wasn’t in the Stratford production) comes after Antony’s speech over Caesar’s body rather than after the more traditional funeral orations. It’s a sound move as it means the action in the second half of the play begins powerfully and we get a sense of how quickly matters spill out of control.

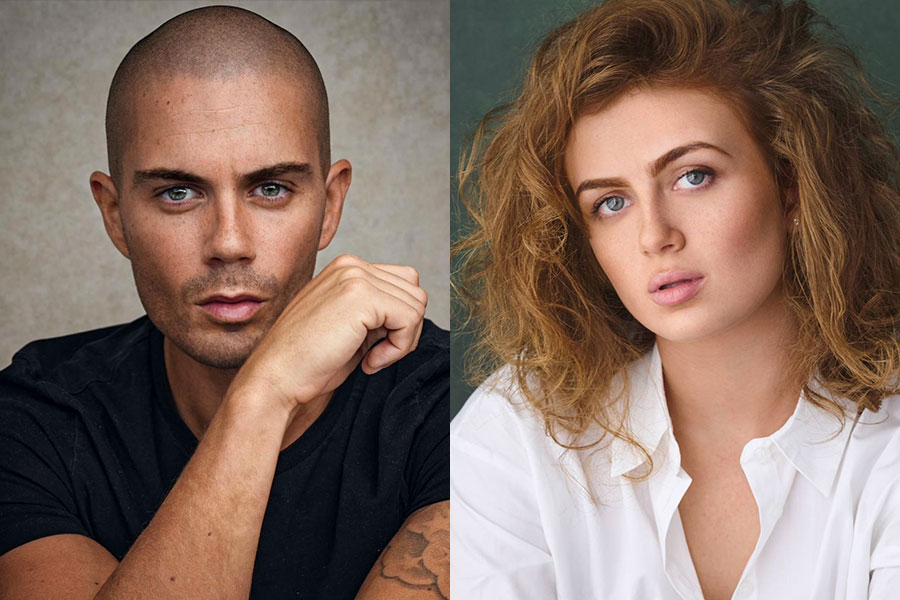

What Doran emphasises is the conflict between Patterson Joseph‘s Brutus and Cyril Nri‘s Cassius. Joseph’s shaven-headed Brutus is mercurial in his rages, quick to his (invariably wrong) decisions. Nri is a much more thoughtful operator, slow in deliberation but like a tightly-wound spring is easily roused to quarrel. Jeffery Kissoon’s Caesar is measured in his delivery, almost artificially so, as if the statesman’s robes fit uneasily on a soldier.

There’s a nicely devious Antony, courtesy of Ray Fearon. He appears among the conspirators with a beguiling smile, as if almost approving of the assassination; it’s a disarming touch. And there are good performances too from Joseph Mydell as a sardonic Casca and from Simon Manyonda’s Lucius, Brutus’ servant who provides the comic touches.

This is a genuinely exciting take on Julius Caesar. What with this and the National’s Timon, theatregoers have been a bit spoiled in the capital this summer.