Tickety Boos

A new survey suggests that over half the people who go to the theatre think that the costs are prohibitive. They also don’t like the price of programmes, or the lack of leg room, or other people rustling sweet papers.

Of course it’s too expensive to go to the theatre, and the peripheral costs of programmes, drinks and show-related merchandise are a disgraceful rip off. But you know that’s all part of the live theatre experience in the heart of London’s glittering West End, don’t you?

It occurred to me last night at the opening of Alexi Kaye Campbell‘s intriguing new play, The Faith Machine, that the Royal Court has now done away with programmes altogether. And that’s far more disgraceful than the West End charging three or four pounds for their “literature”; at least there is some biographical and thematic material buried among the adverts on Shaftesbury Avenue.

At the Court you either have to buy a play text — which no theatregoer really wants to do, unless the author is Tom Stoppard and you want to try and work out what the hell he’s been going on about — or make do with a tiddly cast sheet.

And last night I had to make a special effort to find even that tiddly cast sheet for my guest. Critics are given the play text, often useful for a quick perusal on the way home, or a scramble for a quotation the next morning, but devoid of any interesting or enlightening editorial material, as at the RSC or, especially, the National Theatre.

To be strictly fair, just for a change, the Royal Court never really went in for programmes in a big way. The idea, quite rightly, is that these brand new plays should speak for themselves. But surely the actors want the audience to know who they are and what else they’ve done without having to saddle themselves with a full script.

No reflection, of course, on the script itself, which is handsomely produced on this occasion by my old friend Nick Hern, who incidentally often retains amateur performing rights in the plays he publishes. For the duration of the production, the script, retail price £9.99, is sold as the programme for £3, which is good value, but not really a programme.

But should you have to buy it in order to find out that Kyle Soller, for instance, has appeared in very little so far, but twice at the Young Vic?

Even then, you would have had to have seen those Young Vic performances — as the Gentleman Caller in The Glass Menagerie, and as Khlestakov in Government Inspector — to know how brilliant and extraordinary they were.

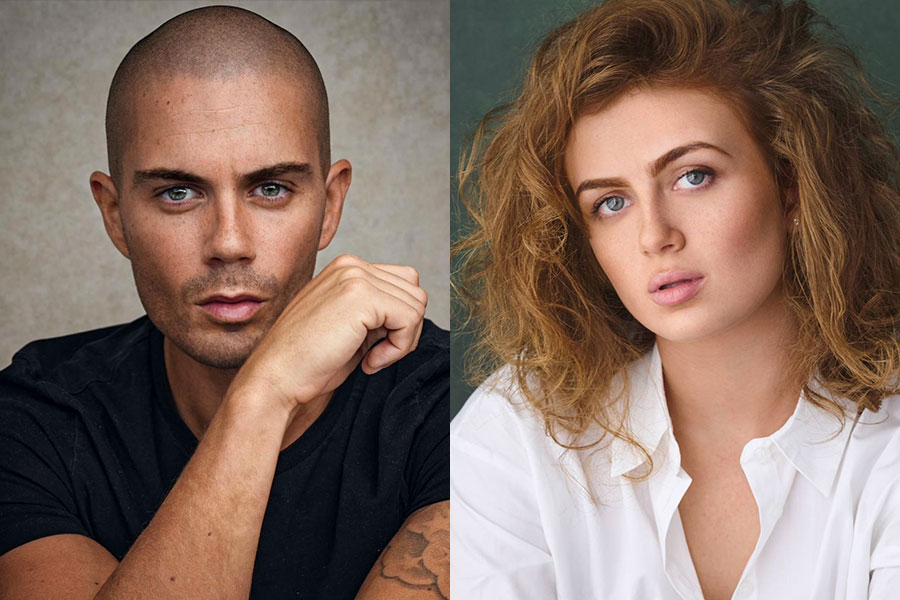

Soller has a face like a banana, a chin like Dan Dare’s, and a mop of ginger hair that makes him occasionally resemble Ethel Merman. He is a wonderfully expressive actor, and also a wonderfully still one. He’s a real new star in the making, and it’s surely no more than an appropriate hint when Ian McDiarmid throws a few lines of Hamlet in his direction.

In The Faith Machine, Soller is very well partnered by Hayley Atwell as a rather unlikely journalist who’s seen action in Iraq and Afghanistan for a glossy magazine. Hayley’s fascinating, too, but in a different way from Soller: you’re never really convinced of how good she is, which is part of her charm.

Again, the programme text reminds you how very little stage work she has done, but she was excellent in A View from the Bridge opposite Ken Stott as her troubled dad — she sure picks tough paters; Ian McDiarmid‘s spouting refusenik bishop is trial enough even before he becomes spectacularly incontinent — and sweet but only so-so as Major Barbara at the National.

Other audience dislikes listed in the survey include having to drink from plastic glasses, queuing for the ladies’ loos and even being asked to get “involved” in shows. Is the spirit of adventure completely defunct in our theatre-goers?

I agree you should be allowed to insist on a glass for your beverage if you are not returning with it to the auditorium. But, come on, some of my best interval conversations are conducted while hanging around the queue for the ladies’ loos. And like most of my colleagues — Lyn Gardner and Henry Hitchings, especially — I can’t wait to be asked to be “involved” in a show, if only to exercise my sovereign prerogative of turning down the invitation flat on the spot.

I don’t mind joining in the odd song, especially at panto time. And the audience singalong of the Marseillaise during the Casablanca spoof at the Pleasance was an absolute highlight in Edinburgh this year.

I don’t necessarily go to the theatre to have a good time. Nor should you. It is a function of the very best theatre to make you feel angry and uncomfortable — and outrageous ticket prices, disgusting warm wine and lousy programmes are all part of the true theatre-going experience.