Review: Coriolanus (Sheffield Theatres)

© Johan Persson

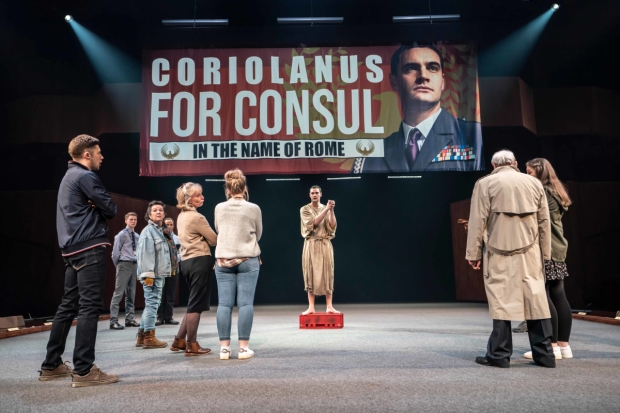

Robert Hastie's fast-moving production of his intelligently cut adaptation of Shakespeare's Coriolanus is all about the use of space. At the outset the vast Crucible stage is entirely empty, with sunken seats on three sides for the senate. During the evening it will fill, to some extent, with furniture and props – a podium, perhaps, or the fence around a military installation – but much more with people, the main cast of 14 supported by nearly 20 members of Sheffield People's Theatre.

To a very real extent, however, the whole theatre is the stage. At the start it's hardly unusual to have the mutinous citizens entering through the audience. What is more unusual is the way in which this scene and many others are played with characters halfway back in the auditorium. At times the whole theatre echoes with arguments and chants, often with the house lights up.

Coriolanus is a strange play. On the page it can read almost as satire; on stage the towering figure of Coriolanus assures the work's status as tragedy, but the satirical element shouldn't disappear. Hastie gets full comic value from the "Oh, no, he's off again" looks that Menenius and Cominius exchange when Coriolanus launches into another intemperate rant, but he never turns his central character into a caricature.

Hastie preserves the balance in a political play where both sides are more or less wrong. Coriolanus is certainly heroic, though his nobility may be in question when he betrays both Rome and the Volscians. The contempt for the lower classes that prevents him from performing what is little more than a traditional gesture suggests that his appointment as Consul would have been a very bad idea.

On the other hand the citizenry who mutiny against him are fickle – unthinking and self-serving – and the Tribunes who lead them mere demagogues with a craving for power and no idea how to use it. Shakespeare clearly was unimpressed by the glory that was Rome!

Sally Wilson's modern costumes serve the general sense of clarity that marks this production. In the opening minutes, for instance, the casual training gear of Caius Martius (later Coriolanus) and the immaculate suit of his mentor, the senator Menenius, reveal their very different attitudes to conventions and appearances.

Tom Bateman is a thoroughly believable Coriolanus. Not conventionally proud – he has no taste for public praise, slouching uneasily in his chair as Cominius speaks his virtues – Bateman is possessed by a much more dangerous combination of restless energy and utter contempt for the ordinary citizens of Rome. For much of the time he can hardly stand still, a striking contrast to his submissive posture when his mother, Volumnia, pleads with him to spare Rome.

Casting his wife, Virgilia, as profoundly deaf – Hermon Berhane signs her speeches and the audience is aided by surtitles – helps to suggest a gentler side to Coriolanus in his silent signing response, a contrast to the speech and vigorous mime employed by Volumnia. Stella Gonet's performance in general is volatile and passionate – patrician certainly, but not a stately Roman matron. Equally keenly defined is Malcolm Sinclair's Menenius, perfectly poised and witty, so much at home in the senate that he sits back in his chair with his feet on his desk. His own contempt for the plebs is cloaked in his habitual urbanity, only breached when Coriolanus rejects his peace mission.

Theo Ogundipe – wild of hair and beard – establishes the "otherness" of Aufidius, the general of the Volscians, and sharply defined performances throughout feature some effective gender-blind casting: Katy Stephens' staunchly establishment Cominius, Alex Young and Remmie Milner suitably self-righteous as the Tribunes, and Kate Rutter's First Citizen, enthusiastically speaking whatever mind she has with her.

Often noisily dramatic, but with nice variations of tone, this Coriolanus consistently involves the audience, even if Shakespeare himself prevents much sympathy for any of the characters.