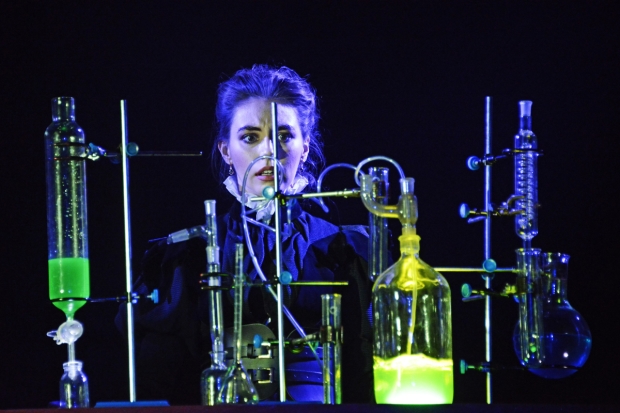

Review: The Fall (Southwark Playhouse)

(© Helen Maybanks)

When you're young and full of zip, it's nigh impossible to imagine being ancient, wrinkled and helpless. In the National Youth Theatre's production of ''The Fall'', by James Fritz, a cast fizzing with energy deliver a stinging, sharp-witted show as they examine just how bad it can be to grow old in a world where housing and social care are in crisis. The answer is… really bad.

The play's three scenes also question how far the dispossessed young can be expected to empathise with the frailty of elderly relatives who have enjoyed a lifetime of prosperity. And the answer here is – not very much.

The bottom line in The Fall is, when you're old, everyone wants you dead. And in this brave new world, you can take the exit option yourself. No pressure. Just that your family will get a big cash payout if you do choose to pop off. To press the point, designer Christopher Hone's centre-stage bed revolves on its axis, as if shuffling its occupants off their mortal coil one by one.

The opening scenario, where two young people sneak into a house for sex, only to find a dying man in bed, is a tour de force for the sparkling Niyi Akin as the Boy determined to impress his Girl, Jesse Bateson. These two make a powerful partnership. He woos her with song and an unfeasible number of press-ups, before recoiling in horror at their discovery, while the Girl restores dignity and compassion to the fading man's final moments.

© Helen Maybanks

In the second scene, a lifetime of hardship and impossible choices whizzes by to the accompaniment of endless bedmaking. Troy Richards brings gravitas to the loyal son, while Sophie Crouch is excellent as the warm but long-suffering wife who just might have smothered an old woman to be sure of a financially secure future.

The final scene is perhaps the most heart-wrenching. Elderly people are crowded into shared rooms to live out their final days, ministered to by an online nurse, while under almost intolerable pressure from Liaison (crisply performed in post-modern Ratched style by Lucy Havard) to end it all by volunteering for euthanasia.

Sparky Josie Charles (A) and the altogether charming Madeline Charlemagne (B) attempt to bring some joy back by embarking on a lesbian love affair, but that's quickly scotched by telltale D, Jamie Ankrah, whose bullying swagger masks the despair of a man whose family will not be coming to the rescue. Jamie Foulkes has an extremely touching delicacy as the apologetic C, who told his family not to visit. And they haven't.

The only person who really seems to care about anyone else is the Nurse. Joshua Williams lends a hypnotic, softly spoken calm to the role of bringer-of-death, as it's only once you've committed to suicide that you'll be cared for by another living person.

If this all sounds too grim for words, it is, but in a very good way. This is an intriguing production with a fine cast who, under Matt Harrison's direction, do justice to a thoroughly disturbing play.