Purple Snowflakes and Titty Wanks at the Royal Court – review

The final call for this monologue asks the audience to take their seats for Purple Snowflakes. But it's the unmentionable second half of the title that gives a better clue to its scabrous, no-holds barred impact.

Sarah Hanly has written and performs this heart-felt piece, clearly semi-autobiographical and full of insight into what it feels like growing up as a lesbian (or purple as she decides to call herself) in a convent school in County Wicklow and beyond. First seen at Dublin's Abbey Theatre, it's now getting its UK premiere at the Royal Court Upstairs.

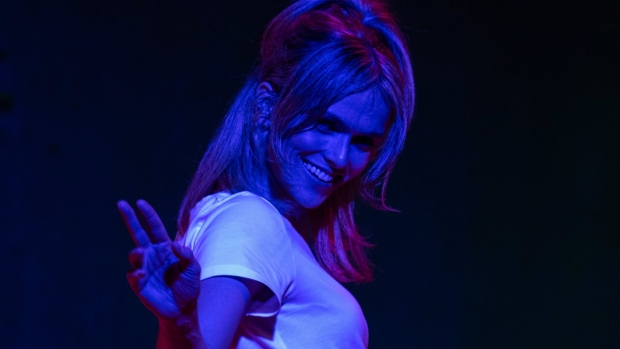

Hanly's a vivid, swaggering stage presence, in white T-shirt and pink bumbag from which she extracts everything from a pink telephone to a fake set of dangling testicles (for a school performance as Creon) as she embodies the story of Saoirse who finds her way to drama school and ultimately to a happiness through a mire of misunderstanding in a hostile world.

On Jacob Lucy's vivid green set, with a ramp around a deep pit in the centre, and bathed in Elliot Grigg's evocatively changing lights, she takes us through a series of sexual encounters, from the discovery of orgasm with one of her schoolmates and a set of pearls in the church vestry, to the aforementioned titty-wank with an unprepossessing boy in a church car park as a bishop walks by, to a full BDSM affair.

The encounters, described in imagined conversations with her sister and her best friend, are often raucously funny. But under their laugh-out-loud punch, there's a terrible sadness, as Saoirse describes the childhood unhappiness triggered when her father walked out (they held a mock funeral for him) and her mum moved in with the local priest. She talks with graphic and haunting frankness about bulimia (chocolate tastes good on the way down and the way back up, and cornflakes scratch) and the terrible confusions of an adolescence scarred by a lack of honesty about religion and sex.

Some of the narrative barely rises above anecdote and the ending is too rushed and highly unconvincing. It is possibly also true, but Hanly hasn't quite transmuted events that you feel she perhaps experienced into drama that you believe she has. But she is a wonderfully fresh, exuberant voice, clever with words and the way she manipulates them.

She is beautifully served too by Alice Fitzgerald's direction which marks with tender gravity the undertow of unhappiness, while making the surface of the play vigorously and energetically enticing, with dancing, glitter fountains and even a spurting bottle of hand sanitiser all conjuring the scenes described with an electric panache. It makes you want to see what both come up with next.