Review: Pah-La (Royal Court)

© Helen Murray 2019

Dousing yourself in fuel and lighting a match must surely be one of the worst possible ways to attempt suicide. But the overwhelming power of this gesture by a Tibetan Buddhist nun is enough to ignite a surge of public unrest that jeopardises the future of a non-violent culture in this play from Abhishek Majumdar.

Pah-La – which means father – is based on real stories emerging from the 2008 Lhasa riots. The David and Goliath battle between Tibet and China is played out here within two families, where both fathers spectacularly fail their daughters.

The undoubted heroine is nun Deshar, who wants to voice her opposition to the Chinese soldiers who destroy their monastery, without hurting anyone else. But despite being a Buddhist who's proved capable of breaking a soldier's jaw, she defies the order to be silent not by violence, but by setting herself alight on an isolated mountain railway line.

The consequences of this act are devastating not just for her personally – she is more than ready to die – but because of the violence it unleashes among her fellow Tibetans, denounced as savages by the Chinese commander even as he orders the crippled nun to be burned again.

Debbie Hannan's production has taken a long time to come to the stage, and many of Majumdar's acknowledgments are to brave people he cannot name for fear of putting their lives in danger, even today. So this is clearly a story that needs to be told, and a sense of dread and oppression hangs heavily over the play. Extended scenes of pain and torture under questioning are not easy viewing, and the make-up for Deshar's scorched body is gruesomely convincing.

Yet Pah-La also has a curiously hazy and disjointed feel, with long speeches repeatedly reinforcing the same points, rather than developing the narrative or refining the relationships between the characters. While some of the performances are a little uncertain, Millicent Wong is a powerful and convincing Deshar, and Kwong Loke is also impressive as Rinpoche, the Buddhist monk who fears – quite rightly – that Deshar's undisciplined approach will bring trouble from the Chinese.

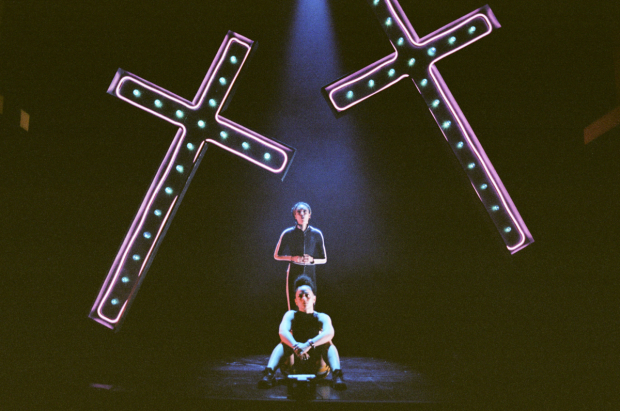

There is excellent work also from movement director Quang Kien Van, and Tom Gibbons' composition and sound design underpins the play's menace throughout. Designer Lily Arnold's backlit set is simple but effective, with some stunning pyrotechnics that feel genuinely alarming within the close confines of the Jerwood.

Ultimately, Pah-La blames all fathers for war and suffering – a sweeping approach which parents in the audience might dispute. And as for the future of non violence? A mother rates the chances of its success in a bitter declaration: 'To live is to hate'.