Review: Misty (Trafalgar Studios)

© Helen Murray 2018

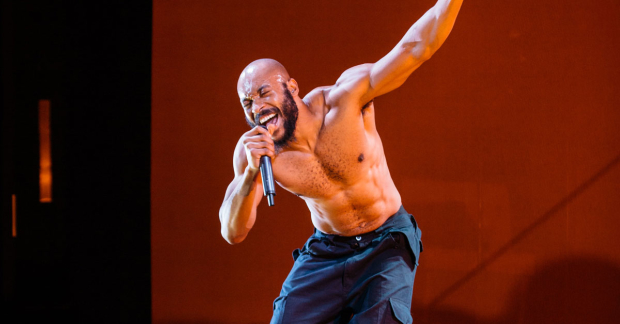

'A lot of crazy sh*t happens on the night bus,' so begins Arinzé Kene's playful, complex and human exploration of what it means to live in London today, of being a black man today and of being a writer today.

It's mainly just Kene and the audience for most of Misty, which starts with him telling a rhythmical, performance-poet narrative – accompanied by Shiloh Coke and Adrian McLeod's pumping, heavy score. There's talk of hoodies, viruses, edgy bus passengers and a fight that breaks out. This is Kene setting a scene of unhappy urban angst. But then, it changes. Kene is always interrupting Misty, switching the form and turning things upside down. Suddenly, we're not hearing about the night bus anymore, what we're hearing is feedback from his friends about his play. They think he's written the most clichéd thing you could write.

The threads of what seem like fiction (is the night bus story real or not? Kene messes with us on that one) intertwine with Kene's own musings on what it means to write a play. He lays bare – with much humour – the challenges he has talking to agents and producers about making something that is true, and that he can be proud of, rather than rushing to fit something into what they want him to write. In this, Kene represents all of us who cut corners, who don't take time to think, who jump to conclusions, who don't question ourselves and why we reach for the closest clichés at hand. It's a dangerous game, especially where art is concerned.

But Misty is also about the changing face of a city and Kene's focus is often on gentrification and how that morphs and changes a place and its people. The viruses, it turns out, are those coming in – the ones setting up their hipster coffee shops – not the hoody wearing Lucas, whose night bus shenanigans gets him into real trouble. In the second half, Misty becomes a call to arms, a call for the protection of culture and way of life that 'trustafarians' are steamrolling over in London. He reminds us of Grenfell and the Black Lives Matter fight, building the volume, singing and dancing until it becomes a rousing siren for change. But then, just a scene climaxes Kene's back to larking around with big orange balloons. It's complicated, he seems to suggest.

Everything is played out to the background of Daniel Denton's vivid video projections which riff on the idea of the city as a living breathing body with blood cells and arteries. And Coke and McLeod are constant, bolstering presences, occasionally stepping away from their instruments and playing characters themselves. Director Omar Elerian makes sure that Kene never misses a beat. Where occasionally the piece tries to cram too much in, never settling long enough on its many ideas it is nevertheless clever, affecting and truthful work. And Kene's no doubt a name we'll be seeing much, much more of in the future.