Review: Lonely Planet (Trafalgar Studios)

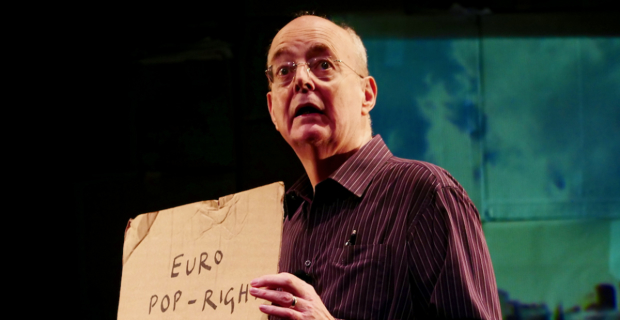

© Richard Hubert Smith

Lonely Planet was written within twelve months of Angels In America, and similarly explores the fallout from the AIDS epidemic in North America. Whereas Tony Kushner's extraordinary two-part epic explodes with invention and ideas, however, Steven Dietz's 1993 play – his most performed work – is a much quieter affair: a simple two-hander, featuring two liberal-leaning gay friends both dealing with the horror of HIV differently.

In an unnamed American city in the late eighties, Jody (Alexander McMorran) runs a map store, catchily named Jody's Maps. He's a moody, bookish, belt-and-braces guy – corduroys, scraggly beard, awful barnet. Carl (Aaron Vodovoz) is almost his antithesis, a bubbly, hundred-mile-an-hour babbler – baseball jacket, feathery moustache, even worse barnet.

At first, it's difficult to get a grip on their random, rambling conversations, and on their situation. Why is Jody refusing to leave his map store? What does Carl actually do for a living? Why is he slowly filling up Jody's shop with a random assortment of rickety chairs? Are they both still alive? Are they figments of each other's imagination?

Slowly, though, you start to tune in to Dietz's dialogue and to his eccentric characters. Carl is a serial liar – depending on the day of the week, he either works as an art restorer, a mechanic or a grubby journalist at a grubby newspaper – but he really spends his days emptying out the flats of friends who have died from AIDS. Hanging on to their chairs is how he remembers them. Lying is how he copes. Jody – a ball of tetchiness, anxiety and denial – has yet to get himself tested. He'd rather forget about it all and prattle on about the Mercator projection.

At times, Dietz's play is stirringly sensitive, thanks in part here to two wonderfully detailed performances from McMorran and Vodovoz. The final few scenes are quietly crushing in particular, exposing both the heartbreak and horror of Jody and Carl's situation, and the sheer cruelty of a society in which tens of thousands of men could die from a disease without the Reagan administration lifting a finger.

At times, though, like Angels in America, it's gallingly keen to show off. Dietz's symbolism can stray towards heavy-handed (there's a lot of it – maps, chairs, telephones), and some of the more verbose, winningly articulate speeches handed to both Jody and Carl scan like an undergraduate essay. Words, words, and yet more words.

Ian Brown's straightforward staging – the play's UK premiere, transferring from Chiswick's Tabard Theatre ahead of July's London Pride – and David Allen's dusty, detailed (and Offie-nominated) map shop set keep this showboating in check, though. It emerges as it should – a modest and moving account of a terrible, terrible time.