Kings of War (Barbican)

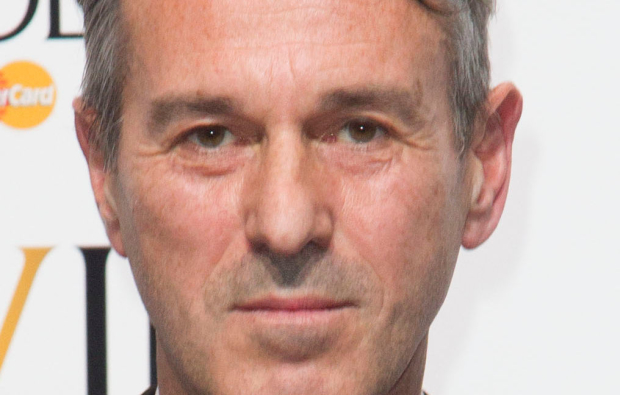

Ivo van Hove is the hottest of hot directors, thanks to his vivid re-imaginings of A View From the Bridge and Antigone, not to mention his brush with David Bowie in bringing Lazarus to the stage. Kings of War sees the brilliant Belgian and his Toneelgroep Amsterdam returning to the Shakespearean terrain they trod so successfully with the Roman Tragedies, a six-hour journey from Coriolanus to Antony.

Here the mash up lasts only four and a half hours (nearly five on press night), and encompasses Henry V to Richard III with a fiercely truncated Henry VI parts one, two and three in between. The intelligence on display is never less than staggering, but Van Hove’s decision to concentrate only on the exercise of power sometimes feels reductive rather than truly insightful. I was always intrigued, but rarely engaged.

What’s unmistakable is the sheer rigour of his rethinking. The evening opens with a photograph of Prince George and a photographic count-down of British monarchs back to Henry V, who we first see – via the huge video screen that dominates Jan Versweyveld‘s bunker-like setting – prematurely picking up his father’s crown in a white corridor that stretches around the rear of the stage.

As the action progresses both video and that corridor have an increasing role to play, revealing things that have been hidden – murders, the fears of soldiers before battle, dead bodies, political machinations, even a flock of sheep. What we see on screen is always revealing and often startling; Henry V’s Harfleur call to arms is a nasty bit of wartime propaganda; Margaret and Suffolk kiss hungrily; Richard III is haunted by the ghostly images of his victims; blood spurts from arms and dead eyes are milky.

Just as the staging emphasises the most brutal aspects of the plays (and points their meaning with labels such as "diplomatic incident" and "endgame") so the language makes them seem unfamiliar. They are performed in guttural Dutch and retranslated in surtitles, shorn of poetry (no "gentlemen in England now a bed", and just a "winter of discontent" without any glory in the summer) which has the effect of flattening the personalities in the plays.

Henry V suffers from the transposition; he becomes a bureaucratic manipulator in a grey suit, uncharismatic and rather dull, who only comes alive in a courtship scene, staged as if at a restaurant table, where he can’t speak without knocking something over. In a fast romp through Henry VI, the king is seen as a hopeless cry baby, and murder is routine, rapid and vile. (The performances are uniformly excellent, but I particularly loved Janni Goslinga as the unhinged Margaret.)

The most satisfying section is Richard III, partly thanks to an astonishing central performance by Hans Kesting, not at all a comic villain, but a quietly psychotic killer, still as a spider at the centre of his dark web, so in love with himself that he spends a lot of time checking his reflection in a full-length mirror. By the close, he is capering like a horse around an empty stage, an unforgettable image of the corruption of power.

Kings of War runs at the Barbican until 1 May 2016.