The Father (Tricycle Theatre)

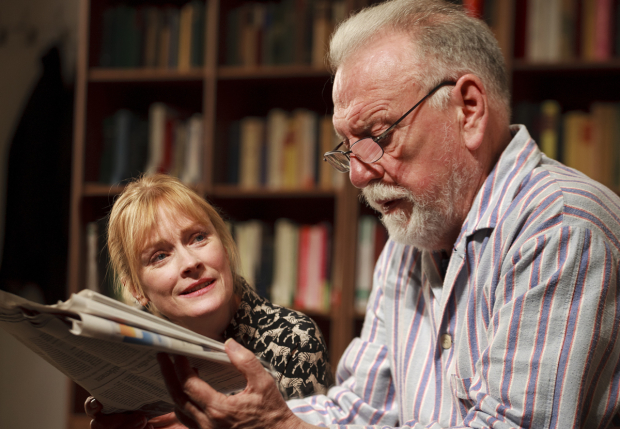

© Simon Annand

No, it’s not Strindberg’s grim scenario, but it is a modern European classic: a contemporary French play about Alzheimer’s, translated by Christopher Hampton, with Kenneth Cranham giving the performance of his life as a suburban King Lear cast adrift on unreliable memory in a piece written four years ago by shooting star Florian Zeller for one of the greatest French actors, Robert Hirsch.

"I fear I am not in my perfect mind," says Lear in the reunion scene with Cordelia, "… I am mainly ignorant what place this is; and all the skill I have remembers not these garments; nor I know not where I did lodge last night."

So it is with 80 year-old André, a retired engineer and (possibly) tap-dancer. Cranham, a craggy-faced, sprightly 70 year-old with a trim white beard and a gift of total relaxation on the stage, is natural, understated, clever and finally almost unbearably moving, trussed up in pyjamas in a place that might be his own Paris apartment, or that of his daughter, or eventually a home – where the bed-side nurse might be the other daughter, enigmatically defined as "woman" (Rebecca Charles).

The daughter-for-definite, Anne (Claire Skinner, lucid and loving, replacing Lia Williams who played the role last October at the Theatre Royal, Bath, where this production was first presented), might be moving to London with her new boyfriend Pierre (Colin Tierney), so she’s trying to employ a new carer (Jade Williams).

But Anne’s husband – here nominated "man" (Jim Sturgeon) – is hanging around, too. We see a confused world of identity and dependence through the eyes of André; but the theatre itself also supplies a different perspective, that of a shifting Pinteresque landscape where characters are defined by subjective and selective memory.

This makes for a tense and intriguing experience: are we watching through the wrong end of André’s telescope, and should we be affected by the volatility of his vision? Or is André’s alienation from his home and family something we all experience to a greater or lesser degree?

His constant cry of "Where’s my watch?" reminds us, too, that our brain plays tricks on us on a daily basis; you don’t have to be as far gone as Oliver Sacks’s man who mistook his wife for a hat to appreciate what’s common to us all.

Zeller, like his compatriot Yasmina Reza (who wrote Art), is fortunate in having Hampton as a translator. The text is spare, elegant, and perfectly aligned with James Macdonald‘s watchful production, which refracts humour through stark images on Miriam Buether’s all-white set. Some scenes are replayed with a different lilt, situations turn back on themselves.

The action is punctuated with the most astonishing black-outs (lighting by Guy Hoare) I’ve ever seen, flashing up like photographic negatives, accompanied by fractured Bach keyboard music and the (one minor blemish) muffled thump of moving furniture. Cranham presides throughout, at once baffled and jovial, letting go, it seems, with serenity and, yes, more than a hint of majesty.

The Father runs at the Tricycle Theatre until 20 June 2015. Click here for more information and to book tickets.