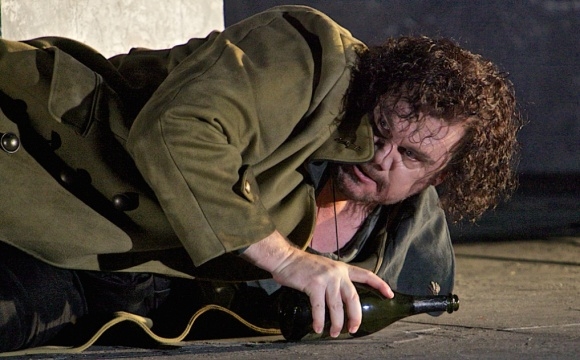

Stuart Skelton talks about Otello, Tristan and the one role he will never sing

© Francis Loney

The Australian heroic tenor Stuart Skelton makes his role debut tonight in ENO’s new production of Verdi’s Otello, conducted by Edward Gardner and directed by David Alden, who were his collaborators on the company’s award-winning Peter Grimes. He took time out to meet me at the Coliseum after exhausting back-to-back dress and general rehearsals ahead of tonight’s opening.

We think of you as an honorary Brit over here. Do you get to work often in your native Australia?

I like to think of myself in the same terms! There’s a little bit for me in Australia – we had the Ring cycle last year, and I have a great relationship with the Melbourne and Sydney Symphony Orchestras with Sir Andrew Davis and David Robertson, but the difficulty will always be that it’s very difficult to do Wagnerian repertoire because they don’t have a pit big enough to accommodate that amount of players.

I’ve been back a couple of times, for Peter Grimes and A Streetcar Names Desire, but there are very few opportunities for the sort of repertoire that forms the core of my career. And their precarious financial situation makes it hard for them to plan ahead, whereas most of the singers they’d want to engage tend to be booked three or four seasons in advance.

You’ve called the Coliseum your ‘favourite place on earth’. Why is that?

There’s a camaraderie here at ENO in terms of doing really theatrically compelling work all of the time, and there’s a real spirit of risk-taking and entrepreneurship. They look for ways to work around the fact that they get a smaller slice of funding every time they come to the table, even though the house isn’t getting any smaller. And so much of the work I do here is with my dearest friends in the business.

It’s a two-way street. These guys gave me a shot at a big London stage debut in 2006 in David Alden’s Jenůfa with Amanda Roocroft, even though apart from a Prom concert three years earlier I’d never worked in London before. That’s a major risk to take, but it paid off for both of us. I’m a regular at a company where I have a great deal of love and respect for everyone who works here from the top down – and particularly with Ed, a dear personal friend. I’m really happy that I have a company I can trust implicitly.

Peter Grimes here was one of those serendipitous things; the way that whole production worked, you can spend the rest of your career looking for it to happen again.

Might happen again with Otello?

I think it might! It’s a powerful piece of theatre, musically and theatrically compelling.

It’s famously a role that’s been a step too far for some tenors.

It is. It’s very strange: it’s not necessarily the case that a great Alfredo [in La traviata] would be a good Otello, but there’s also no guarantee that a good Otello would translate well into that same sort of heroic repertoire in other languages. It’s a bit of a standalone in a lot of ways. Otello is so much more the through-composed concept that was seeping in through Wagnerian works.

Whether he wanted to be or not, Verdi was obviously influenced by the Zeitgeist to a certain extent so it’s a much less number-oriented piece of work and has fewer Italian applause points. Once Otello’s on the stage, particularly from Act 2 onwards, he never leaves. That makes it physically demanding of the voice; but the corollary is that Verdi wrote absolutely stunning vocal lines that are never difficult to sing. They’re not angular in any way: they don’t throw you around from one end of the voice to the other within a bar or two. You just have to have your technical wits about you to make sure you’re always on point. Once you can do that you can relax, let the muscle memory do its thing and focus on making the theatre compelling.

Otello is one great mountain, but you’re about to climb an even bigger one as you sing your first Tristan in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Is that role going to be the cornerstone of your future career?

I hope so, I really do. I’ve been putting it off for such a long time, but when this opportunity came to do sing Tristan in a concert performance in my home town with David Robertson and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, it pretty much ticked every damned box and I didn’t have an excuse anymore. It’s the last of the mountains I’m intending to climb.

As your voice has evolved over time, have you reconsidered your decision never to sing Siegfried in the Ring cycle?

Not in the slightest. I can rule it out now, forever and in perpetuity! The one thing that’s really important is that we should be allowed to sing Wagner beautifully; and there is a level at which even the best of the Siegfrieds have had to at some point abandon or at least compromise their beauty of tone in order to make it work. I would much rather hear the really great Siegfrieds sing it than be merely adequate myself. Not only that, in my head there’s the perfect Siegfried sound; I don’t have it, I don’t make it, and I don’t think I could manufacture it.

What other roles have you got your eye on?

I’d love to do Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny at some point. It’s a really interesting work musically and dramatically and it would be a really fun thing to do. But there are so many things that I’ve done before that I’ll never get tired of singing – Siegmund, Parsifal, Grimes – because every time I sing them I discover more about them musically, dramatically and vocally. I’m hoping Tristan will be like that too.

How do you maintain your energy with such an exhausting jetsetting lifestyle?

I think the secret is that if you’ve got any sort of down time, even if it’s only 24 or 36 hours, make the most of it. On more than one occasion I’ve flown home to Florida for only a few hours, knowing I needed just that time at home where I know where everything is. Even half a day is enough. Nothing unwinds me faster. It’s always warm and humid there, and it’s very hard to be stressed when it’s 29 degrees with 104% humidity outside! Nothing good comes of rushing around when it’s that warm so you are forced to slow down, mentally as much as physically.

But it’s the nature of the job. The main thing is to plan accordingly. If you’ve got seven days off, go and have fun. I don’t think anyone in this business should be living to sing; we should be singing to live.