Michael Coveney: Carousel turns for Mary Rodgers, Arts Council cuts both ways

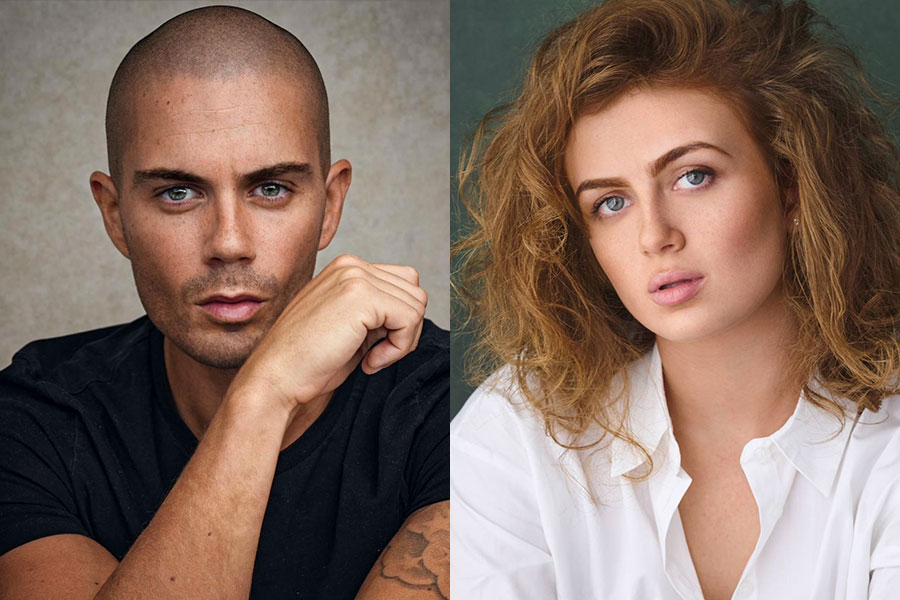

© QNQ Creative

Carousel, as Richard Rodgers' daughter Mary – who died last week aged 83 – once said, was his "most favourite musical of all." So that places it, in his personal pecking order, above Oklahoma! and South Pacific (with Oscar Hammerstein), and Pal Joey and The Boys from Syracuse (with Lorenz Hart), all of which Rodgers had written by the time Mary was 18.

And how Mary and her dad would have loved the powerful new pocket-sized production at the Arcola in Dalston, which doesn't shirk the terrible truth at the heart of the show: that Julie Jordan loves, physically and unconditionally, the bruising fairground barker Billy Bigelow even though he treats her abusively; she's helpless to resist, or to condemn, him.

I saw the show at last Saturday's matinee, two days after Mary Rodgers' death, and a few hours before they lowered the theatre lights on Broadway in her honour. She was, as the New York Times said, at the "red-hot centre" of American musical theatre her whole life: best friend of Stephen Sondheim (she told Sondheim's biographer, Meryle Secrest, that they almost married), composer in her own right, mother of Adam Guettel (composer of Floyd Collins and The Light on the Piazza), and a board member of both Lincoln Center and the Juillard School.

And she had a mixed-feelings relationship with her dad, who was not an easy man, and not too scrupulous in his private life. She loved him, of course, but more for his genius than his friendship. And I think there's something of that unease on both sides in Carousel, with Julie forgiving Billy everything and Billy gaining a sort of posthumous redemption in seeing his daughter at the school prize-giving.

Billy's heaven is another version of his carousel at the Arcola, a brilliant and simple solution to the creepy strangeness of the last act; "the real nice clambake" is anything but, transformed into an orgiastic boot camp with vomiting in buckets and explicit choreographed coupling; and the great anthem "You'll Never Walk Alone" is salvaged from the football terraces in the understated singing of Amanda Minihan as Nettie Fowler and the sweet silver song of the harp solo accompaniment.

There's an affecting "held in" quality about all of the mercifully un-miked singing and especially that of Gemma Sutton as Julie, while Tim Rogers' bearded Billy is a plausible tough guy at odds with his own strength. I hesitate to rave about a small-scale fringe production of a show that belongs rightly in the general public domain; but this is a revelatory examination of one of the all-time classic musicals, and does wonders to rebut the nagging doubts of schmaltz and celestial soppiness that attended even Nicholas Hytner's great National Theatre revival 20 years ago.

Once Upon a Time Upon a Mattress

I laughed myself silly at a late preview of Forbidden Broadway at the Menier on Sunday, and it occurred to me that this musical theatre destination by London Bridge would be an ideal venue for a memorial revival of Mary Rodgers' best known – and only successful – musical, Once Upon a Mattress, based on the Hans Christian Andersen story of The Princess and the Pea.

The show – which has a lovely score of romantic ballads and well-turned comedy numbers – flopped in the West End in 1960, but was charmingly revived by Wendy Toye at the Watermill, Newbury, in 1987, with an unknown Sally Dexter, straight from drama school, letting rip as the uncouth and hilarious Princess Winnifred, the role that made Carol Burnett an overnight star on Broadway.

The cast also included an only slightly better known Douglas Hodge, and I fondly recall not only their performances, but a game of Pooh sticks I played with my small son on a bridge over the untroubled waters of the stream by the theatre. It was a lazy, hazy summer afternoon, and the perfect setting for a touching, funny fairy tale.

The unkindest Arts Council cuts of all

At last night's opening of Julius Caesar, Globe chief executive Neil Constable, resplendent in his brand new seersucker summer jacket, expressed his surprise that news of the Arts Council cuts hadn't been tempered with a reminder of the tax breaks and relief offered to the arts by the Chancellor of the Exchequer a couple of months ago.

This, he reckons would have sweetened the pill, which was not exactly all that unpleasant to start with. There's not much to pick a fight over, though I'm sad to see the Orange Tree punished with a total withdrawal of ACE funds; it must feel like an awful PC smack in the chops to the departing artistic director Sam Walters, and a deflationary thrust in the ribs to his successor Paul Miller.

Edward Hall is feeling the chill, too, with the funding wipe-out for his Propeller all-male touring Shakespeare company. The trouble with Propeller was that, despite continuing high levels of national and indeed international audience success, the project itself was beginning to look exhausted; I mean, how many all-female productions of Shakespeare would you want to see?

The Donmar's all-female Julius Caesar was fine, but the Globe's Taming of the Shrew a few years back was a bit of a nonsense. Same thing with Propeller. Their all-male Shrew, as it happens, was a riot. But The Winter's Tale didn't really gain anything while losing a lot in the occupation of two of Shakespeare's loveliest ladies, Hermione and Perdita. And I think, deep down, Hall must know Propeller's run its course.