Review: Madama Butterfly (Glyndebourne)

© Robbie Jack

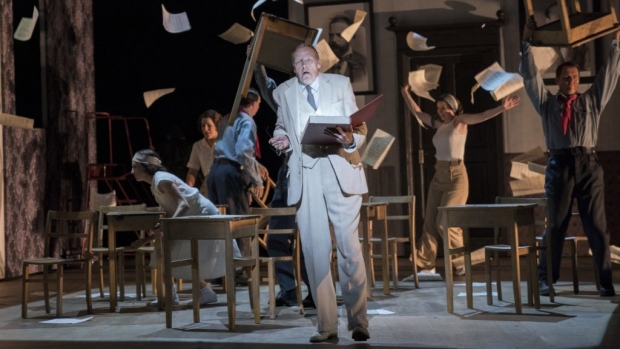

Whatever's been said behind closed doors, it's had an effect. The 2016 version of Glyndebourne's first-ever Madama Butterfly (then for the autumn tour) was only salvaged from ignominy by its singers, so you can bet some hefty questions were asked ahead of its appearance as the opening opera this summer. Annilese Miskimmon's production has undergone significant tweaking, the original's crude gestures have been replaced by decent acting and a problematic final hour has been rethought.

The wilful decision to stage Act One not at Pinkerton and Cio-Cio-San's house but inside Goro's exploitative 'Marriage Bureau' remains as it was, and is probably intractable. Here's the issue: Miskimmon's determination to emphasise the tale's dark underbelly, as if a teenager's sale into a sham marriage wasn't nasty enough already, prompts her to show several other sham marriages too, in an upstage dumbshow of hung heads and despair. Yes, we get it. Advancing the action to the 1950s, the era of the GI Bride, means there's room for a propaganda movie to lure the girls… and before you know it the opera is Miss Saigon's clumsy cousin.

It's all done in a mood of realism, which renders Puccini's orgasmic love duet slightly ludicrous between the filing cabinets and next door's tattoo parlour. Not only that, it denies the music's romance. And who sold the couple an after-hours lock-in anyway? There's a perfunctory glimpse of starlight when Nicky Shaw's set and Mark Jonathan's lighting do a shimmy, but it's too little too late.

Thereafter, thankfully, Miskimmon's production has been improved through revision. The ensuing house scenes now make dramatic sense and are glued into place by a performance of vocal beauty and heartbreaking commitment from American mezzo Elizabeth DeShong as Suzuki, the maid who sees the implications of everything that befalls her fragile mistress. DeShong shines here as she did last year for the Royal Opera; possibly even more so, since here she serves a very different Butterfly.

Olga Busuioc's uneven dynamics led to random lines vanishing below the audibility radar on opening night, and her portrayal of Cio-Cio-San's early optimism was beset by intonation problems. Plus there were moments when stylistically she seemed closer to Berg than Puccini. Yet once the heroine's suffering began in earnest the Moldavian soprano was transformed, her vocal performance boosted by a harrowing identification with her character. It helped that young Rupert Wade was such a convincing Sorrow: a compact little boy, self-possessed yet vulnerable, he gave a point to her travails.

Tenor Joshua Guerrero was a mellifluous Pinkerton whose singing convinced more than his acting, whereas with Michael Sumuel as Sharpless the opposite was true, chiefly because the conscience-stricken US Consul is a role that sits too high for his range. Few of the secondary players made much of an impression apart from Carlo Bosi's strikingly ruthless Goro, although to be fair the writing is more at fault than they are. Characters like Yamadori and the Bonze need a director's guiding hand to put flesh on their bones. That didn't happen.

In a programme note, Miskimmon writes "What is vital for a modern-day audience to understand…" before justifying her concept; but what is vital for a director to understand is that the composer knew what he was doing. Under the sensitive baton of Omer Meir Wellber, Glyndebourne's peerless house band the London Philharmonic Orchestra all but subverted the production's hectoring in a dazzling projection of the score's troubled, ironic romance. Forget the reinvention of relevance; Puccini's Butterfly is pinned to her doom by music.