Carrie’s War

Nina Bawden’s children’s novel Carrie’s War has never been out of print since it was published in 1973, and has been serialized twice on television. This new stage adaptation by Emma Reeves (first seen at the Lilian Baylis at Sadler’s Wells) is a faithful filleting with an added Welsh chorus and an over-stressed sentimental conclusion.

Carrie revisits the scene thirty years later with her son and recalls the period in a warm glow. She and Nick are lodged with Auntie Lou and her fearsome brother, Mr Evans, a shop-owning town councillor, while their new friend Albert Sandwich is billeted in Druid’s Bottom with a Creole “witch”, Hepzibah Green, and her seriously retarded relative Mister Johnny.

Hovering above on Edward Lipscomb’s split-level doll’s house design – which is divided by a wooded area with a silhouetted charred fence (the battlefields? The burnt-out house of the last scene?) – is Prunella Scales as Mrs Gotobed, estranged sister of Auntie Lou and Mr Evans, a widowed eccentric with jewellery and twenty-nine dresses.

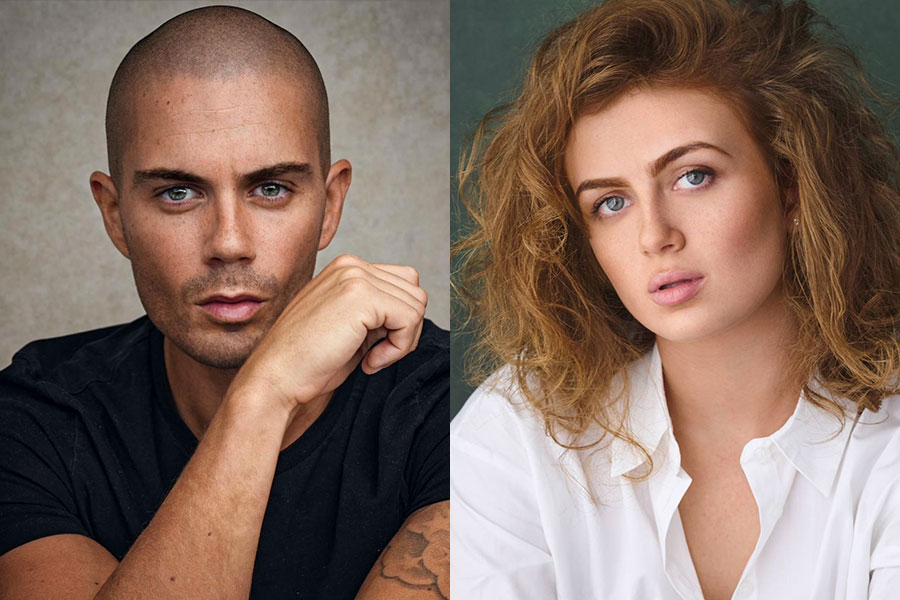

Scales has a ghost-like charm as she fades visibly throughout the play, though one feared for her falling off the set. Carrie and Nick are played by Sarah Edwardson and James Joyce in that over-eager adults-as-children style which is only marginally less annoying than a children-as-children style. They are ten and twelve going on forty-five.

Although Bawden’s Mr Evans is stick thin and mean-minded, Sion Tudor Owen plays him as a roaring bull resembling Brian Blessed, and Kacey Ainsworth as Auntie Lou, best known perhaps as Little Mo in EastEnders, fidgets and fusses with a touching efficiency. Best of all is James Beddard as Mr Johnny, the first time, surely, a genuinely disabled actor has made such a marvellous meal of a disabled role in the West End.

The singing quartet which covers scene changes and sets moods includes the always generous and sympathetic Amanda Symonds doubling with her “good” witch Hepzibah. Andrew Loudon’s direction is competent enough for the show; but is it distinctive enough to guarantee a surprise success?