John Gabriel Borkman

There is something timeless and tumultuous about Ibsen’s tragic drama that finally evades Michael Grandage’s fascinating production, in a new version by David Eldridge (based on Charlotte Barslund’s literal translation), which is taken at a fair old lick and almost leaves you gasping for breath as old Borkman expires on his snowy mountaintop.

Borkman is a ruined financier who has spent five years in jail and now eight years prowling around upstairs, estranged from his wife, Gunhild. Her twin sister, Ella, his former lover, comes to visit, and so does his son, Erhart, who is planning a moonlit flit to happiness and “life, life, life,” with an older woman and a younger acolyte, the piano-playing Frida who happens to be the daughter of Borkman’s loyal old office clerk.

The network of dependency was stretched by Borkman’s fraud and deception, but shattered by his emotional criminality above all else. Ian McDiarmid looks more like a caged wolf than either Ralph Richardson or Paul Scofield did, and he certainly rings the musical variations in his vocal delivery to compare with either of those great predecessors in the role (twenty, and ten, years ago at the NT).

There is something rat-like, too, in his insistence that his time will come again, something comic in his Napoleonic stand of defiance, his magnificent self-sufficiency. When Rafe Spall’s impetuous Erhart makes a false exit to return and contemplate the grim triptych of father, mother and aunt, eaten away with their familial resentments and ancient bickering, you can fully understand why he wants out.

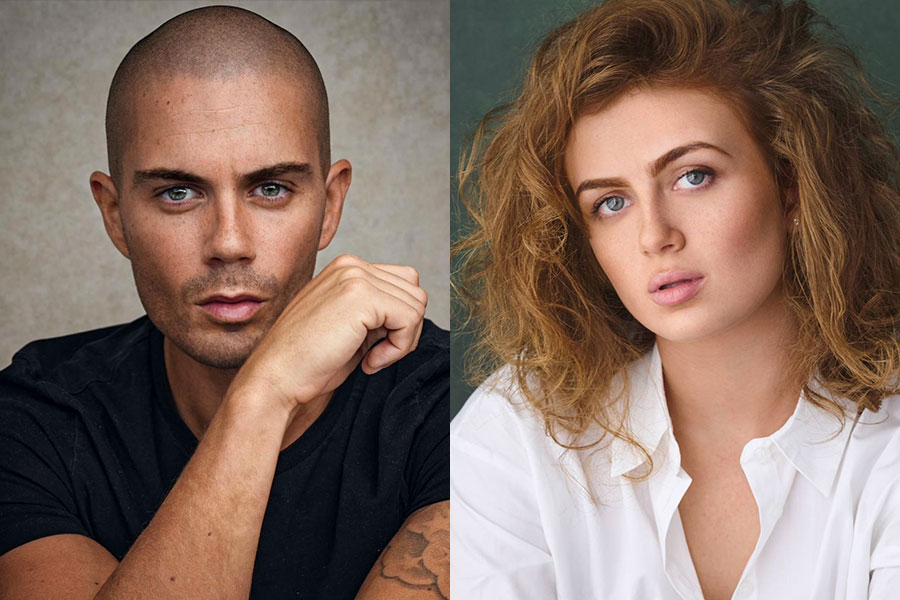

His ticket is the voluptuous Fanny Wilton (a confusing nomenclature in a cast list including Penelope Wilton as Ella Rentheim), seven years his senior, and a drastic alternative to northern European winds in the exotic shape (and generous embonpoint) of Lolita Chakrabarti.

I can see what Grandage is doing. He is undercutting the mystical strangeness of the play by playing it brisk. But this is also an avoidance tactic. There is much compensatory poetry in Adam Cork’s extraordinary soundscore, melding the “danse macabre” that Frida (Lisa Diveney)plays for Borkman with the icy blasts, sleigh bells and cold iron imagery from Borkman’s early days in the mines.

But the third act seems to happen before anyone has felt anything, and the collision of confessions and new resolutions assumes an almost comic character. Maybe that’s the point. Eldridge’s text is certainly swift and smartly turned, and Deborah Findlay as Gunhild finds many laughs in her stoical shrugs and bitter asides. It is left to Penelope Wilton to roar at full throttle when forcing Borkman to confront his own treachery in marrying her sister in order to prosecute his power-mad ascent to the top.

McDiarmid embraces his death with sour enthusiasm. He marches out to the storm like King Lear, but without the mysterious grandeur of Scofield. Maybe the design of Peter McKintosh – of necessity neat and tidy in the small Donmar, the snow face rolls out like a comfy carpet beneath a row of new-looking pine trees – is symptomatic of an intelligent negotiation with the play rather than a full-blooded assault.

– Michael Coveney