Changing of the Guard: Daniel Evans at Sheffield Theatres

The latest interview in our occasional series on Theatreland’s new artistic directors is with Daniel Evans, the new head at Sheffield Theatres, comprising producing house Sheffield Crucible, just reopened after a two-year, £15.3 million renovation, and the Sheffield Lyceum next door, which mainly receives touring productions.

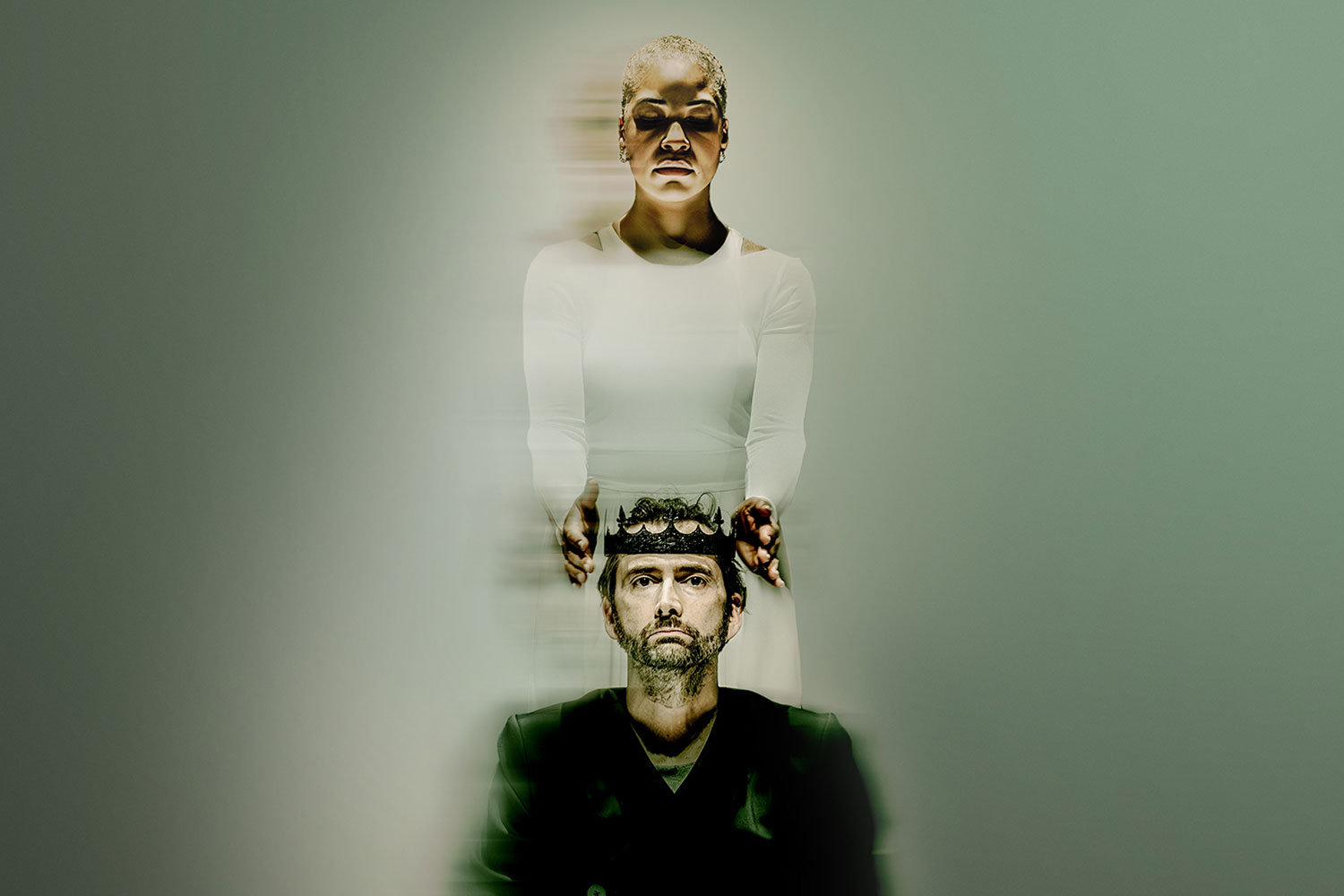

Evans stepped into the position, which had been vacant since December 2006 when Samuel West resigned ahead of the closure of the Grade II-listed Crucible, last June, but officially launched his inaugural season last night, and the new Crucible, with his own production of Christopher Hampton’s version of Ibsen’s 1882 classic An Enemy of the People, starring Antony Sher and the largest chorus of local residents ever seen on the Crucible stage.

Having established himself as a classical actor at the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre, Evans first broke into musicals ten years ago playing the title role in John Caird’s NT production of Candide. He was nominated for an Olivier for Candide and later went on to win Best Actor in a Musical twice over for other Sondheim musicals: in 2001 for Merrily We Roll Along (at the Donmar Warehouse), and in 2007 for Sunday in the Park with George (for which he was also Tony nominated when it transferred to Broadway, following initial runs at the Menier Chocolate Factory and in the West End).

Evans only started directing five years ago and, prior to An Enemy of the People, had mounted mainly small-scale productions, including two Peter Gill plays at the Young Vic and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

What was your first experience of Sheffield Crucible?

It was a production of Six Degrees of Separation. It was fantastic because it was my first time seeing this amazing space. I remember it really, really clearly. I later worked here twice and any actor that has worked on the stage will tell you how amazing and thrilling an experience that is for all kinds of reasons. It’s the fact that there are a thousand people, all on the same level – there are no circle balconies. It’s a very, very democratic space. No one’s more than 15 feet away from the stage. And because of the length and width of the thrust, you feel like the audience is with you at every single point. That focuses the energy of the room like no other place I’ve ever played. It’s about dimensions, I guess – which was one of Tyrone Guthrie’s big, big discoveries. The Crucible this was the final one in those series of buildings that were modelled on his original version. They obviously got it right.

Why else did you want the job of

artistic director at Sheffield?

I’d also had a great time in the city when I worked here before. I had fantastic landladies and I found the city very, very friendly and very open. And I’d wanted to run a building since I was a teenager, though I didn’t tell anyone. It was my little secret. After I came back from Broadway with Sunday in the Park with George, I felt that I wanted a new challenge. I think I’d been looking for one for quite a number of years actually, that’s why I started directing in the first place. So this combination of wanting a new challenge and wanting to run a building and the fact that Sheffield was suddenly advertised made it a complete no-brainer for me.

What made you want to be a theatre director

in the first place? And to run a building?

The acting came first, I was a child actor in South Wales. I’ve been working for about 11 or 12 years as an actor and for perhaps the last five years of it I’d been gradually thinking that, from time to time, I would like more input over the whole evening, not just my part in it. Of course, the bigger the part you have the more input you have, but there’s nothing like having the input the director has. He works with the designer and his production team and his creative team to create the whole evening. That was something that became more and more enticing to me. I guess it was just a need for more control in one way, more power in another but not in a megalomaniac way. It’s just me wanting to be exercised creatively I think.

From the ages of 14 to 18 I was really lucky to be able to go to Stratford and London almost every weekend for a period, either to the National or the RSC. One of the joys of that time was seeing an entire season of work, and seeing the same actors in different plays. Sometimes in a day you could see the same actor playing two different parts, one in the afternoon and then another in the evening. It always amazed me. And I thought a wonderful thing it must be to be able to imprint a tone not just on an evening but on a whole season, on a place or a building. After I went to Guildhall and trained, I was fortunate that all my most enjoyable experiences have been attached to these subsidised houses: Stratford, the National, the Royal Court. It’s so wonderful to feel the support of all the people that work at these buildings permanently. They’re not just admin people doing a hell of a lot of paper-pushing, they’re people who genuinely care about what goes on in the building. That’s always fascinated me.

There were two years without an artistic director at Sheffield, while the Crucible was closed. How has it been for you stepping into that void?

I’ve been very, very lucky in one sense because there is a feeling that the organisation has needed an artistic leader and lots of people have said to me how glad they are that there finally is one. It means that I get to inherit this amazing building that’s just had £15.3 million spent on it – that’s the reason that there hasn’t been an artistic director, because the building’s been dark to facilitate the development. So I feel very privileged and very lucky that I not only get to do this brilliant job, but I get to do it in a 21st-century, state-of-the-art building.

How would you rate your predecessors prior to the closure?

I had two wonderful predecessors before the closure in Samuel West and Michael Grandage. Obviously, I’m going to be full of praise for them because of the work that they did here and the people that they are. They’ve been a great example to me, and I’m aware that they are big shoes to fill. Michael took over the theatre and really revolutionised the place. He turned it around and made it a big, big success and suddenly Sheffield seemed to be very much at the centre of things. Sam then consolidated that work and advanced it. So they are two great role models.

What do you consider your most immediate

challenges & rewards in the job?

The first is directing the opening production – that’s a big one! The second thing is about thinking long term. It’s nice to see that the building is getting so much attention at the moment because of the re-opening. There’s a sense that Sheffield as a city has really missed its producing theatre. The challenge is fulfilling the expectations and continuing to do so by inviting people into the building and producing work that they find interesting and stimulating.

Give us an overview of your inaugural season.

I think the biggest thing is the huge variety. We open with a classic play, Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People; then we have a world premiere, Sisters< about British Muslim women; then Sam Shepard’s American classic True West, which will play opposite Roy Williams’ play for teenagers, There’s Only One Wayne Matthews; then we have Alice, a brand new adaptation of an English 19th-century novella on the main stage; and we finish in the Studio with the English regional premiere of Polly Stenham’s award-winning play That Face. So you can see that there is a wide variety of shows appealing to a wide variety of people, I hope.

What can we look forward to beyond that?

We’ve also announced that in September there will be some Shakespeare – John Simm is coming to play Hamlet for us. I don’t know whether that will transfer to London afterwards. The important thing for us is that we’re making it for Sheffield, and in the first instance, if people want to see it, they should come see it in Sheffield. That’s where we start with all of our productions. Beyond September, there will be more new writing in the first full year, and there will be a season celebrating a living British playwright in which we hope to produce that person’s plays in all three of our spaces, which will happen in the spring of 2011. How can I say this without giving the game away…? No, I think I’ll leave it at that for now!

What’s the length of your contract?

It’s open-ended. I guess the time will come when I, or the city, might feel that it’s time for someone else to have a go, but I’m only in my first year so I’m not thinking like that yet. I’m not thinking about leaving. I’m making a commitment.

How will you measure success?

Of course, audience figures will tell us. Last autumn, our audiences at the Lyceum increased by 10%, which is great – now it’ll be interesting to see how the audiences react to a new building opening. More than that, I would like the people of Sheffield to feel like the building is theirs and that they somehow have an emotional investment in it. That also means what kind of conversation they have with us. Not just whether they come to see the play, but how they use the building and how they view us. Those are things that are quite complex and subtle and not always easily measurable.

What would you say to entice first-time visitors to Sheffield?

First of all, I would say that Sheffield as a city has changed beyond recognition in the last five years. So much has been spent on urban planning. We’re one of the greenest cities in the UK and we are a mere two hours from London’s St Pancras International or from Newcastle, we’re smack-dab in the middle of the country. But I think the most important thing to say for theatregoers is that if you want to see the most dynamic space in the country, then you have to see a play at the Crucible – until you’ve experienced that, I would argue that you haven’t really had an amazing experience in the theatre.

Finally, why do you think theatre in general is important in modern Britain?

Because I think it changes people’s lives. It offers an opportunity for us to look at the very worst and the very best of us and through that, hopefully, to make ourselves better.

– Daniel Evans was speaking to Terri Paddock

Evans’ production of An Enemy of the People, starring Antony Sher as Dr Tomas Stockmann, opened at Sheffield Crucible on 17 February (previews form 11 February) and runs until 20 March 2010.