A Raisin in the Sun (Sheffield Crucible)

The title is singular, the play is not. Lorraine Hansberry‘s classic rolls an inheritance drama, an American dream play, feminist argument and a family portrait into one, and then turns the lot over to the consideration of race. In a single swoop, A Raisin in the Sun changed the colour of the great American play.

Almost 60 years on, it’s still rich and the struggles it shows so eloquently, of African Americans locked out of white America, caught between assimilation and exile, are still raw – both a testimony to Hansberry and an indictment of America.

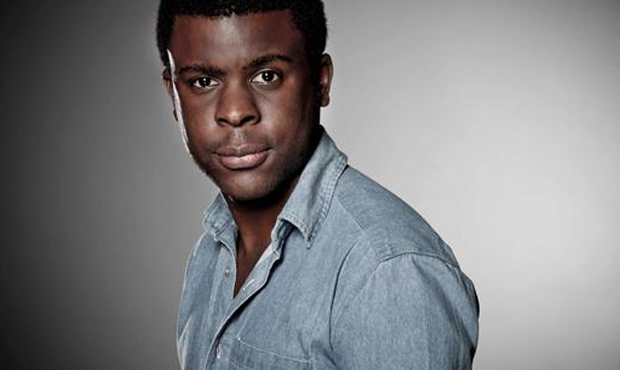

Squished into their two-bed "rat-trap" in Chicago, the Younger family want what every American family wants: to get on in life. Walter Lee Junior (Ashley Zhangazha), a chauffeur, wants his own business; his wife Ruth wants her own home. Beneatha, Walter’s sister, dreams of becoming a doctor. An insurance of $10,000 makes a lot possible, but their mother Lena (Angela Wynter) opts to put a down payment on a house in a well-to-do white neighbourhood, Clybourne Park.

Though the play’s defining moment is that neighbourhood’s response – they send a ‘welcoming committee’ to buy the family out – it never reduces the uphill struggle of African Americans to a single instance. Hansberry shows, brilliantly, how struggles stack up and multiply. Walter’s lack of self-worth makes him testy at home. Ruth ends up trapped indoors – a whole four years before Betty Friedan. Before she can define her dreams, Beneatha has to define herself – how African and how American.

Dawn Walton‘s production never demonises white America, but flags systemic issues. It understands that discrimination smiles as it shuts the door closed. Mike Burnside’s squirming Karl Linder is all respectful civility, but betrays himself bit by bit: the way he swallows "you people," the way he claims to want dialogue, then gabbles non-stop.

A touch stagey, with blocking you notice, Walton’s production nonetheless has a keen sense of daily battles and frustrations. You hear it in the way the family talk: both Beneatha’s posh, white ‘hairlo’ down the phone and Walter’s clipped service speak – yessir, nosir – deny their own natural dialects. You see it in the hands on deck needed to keep everything shipshape: the ironing, the arguing, the cockroach extermination.

It is, above all, a play about family. Walton’s cast have the easy intimacy of people that know each other’s bathroom routines. When Walter returns to romance his wife, Susan Wokoma‘s Beneatha smiles as she screws up her face. Zhangazha’s Walter always has his family’s interests at heart. It’s to them he wants to prove himself, and when Wynter’s Lena scolds him, you see the boy beneath the man.

Every so often, Walton nudges into expressionism, filling the flat with orange light. It’s as if the play’s trying to burst its seams, to break beyond its Broadway-friendly naturalism. It’s a smart move – nodding to the play’s own assimilation in reclaiming the family drama – but it could go much further. Still, does something this rich need reinvention?

A Raisin in the Sun runs at Sheffield Crucible until 13 February and then tours.