Race

Mamet keeps things black and white (and not very Jewish) throughout, suggesting – or, and this is a crucial difference, allowing his characters to suggest – that we are all racists under the skin if not on the top of it. You think black people always hate white people, asks the black attorney? You betta believe it.

Terry Johnson‘s almost unbearably taut production, set by designer Tim Shortall in a large, library-style office with a soar-away inset of the Manhattan skyline, never flinches in the face of Mamet’s gruelling exposition. Nor do his actors, who are quirkily cast.

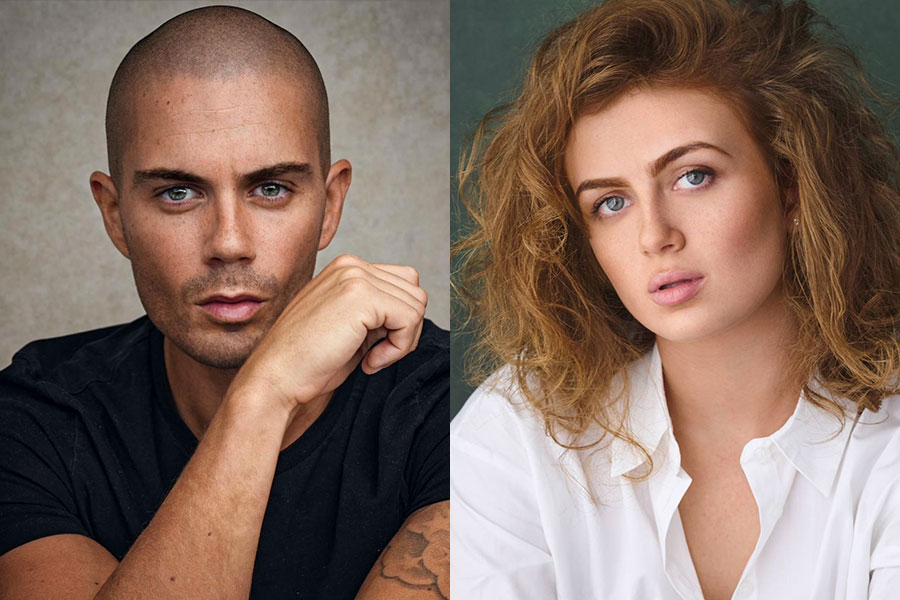

Jasper Britton is the senior partner, Jack Lawson, hypnotically unpleasant, the opposite of smooth, devious and calculating, glistening like a snake, while Clarke Peters as Henry Brown is a wilier, older specimen, so straight-talking in that glorious baritonal voice of his that you feel his statements to the client will cut him clean in two.

And the client himself, Charles Strickland, is played by Charles Daish with a self-effacing hesitancy that seems to contradict Mamet’s own view of him. It’s as though the actors, seeking a different kind of colour in their characters, have given up the ghost and played wilfully, and wherever they can, against type.

All except Nina Toussaint-White as the junior lawyer, also black, who has been the subject herself of covert investigation by her boss and has, in turn, sleuthed some damning personal evidence on Strickland off her own bat.

Everything here is unfair, underhand, nasty, riven with an innate racism no-one is big enough – or, Mamet suggests, dishonest enough – to override with a sense of decency or morality.

It’s a bleak, uncomfortable message, and one expounded in a brutalised language that is deliberately drained of Mamet’s more usual zing, rollicking rhythm and irresistible swagger. There’s nothing of joy in this piece. You want joy? Go see a musical.

The case against Strickland, before it even gets to court, may stand or fall on how many sequins were shed by the allegedly ripped dress. But even that pales beside the prime purpose of the play, which is to provoke exactly the sort of glum and slightly depressed reaction this review unavoidably illustrates.