Review: The Secret Theatre (Sam Wanamaker Playhouse)

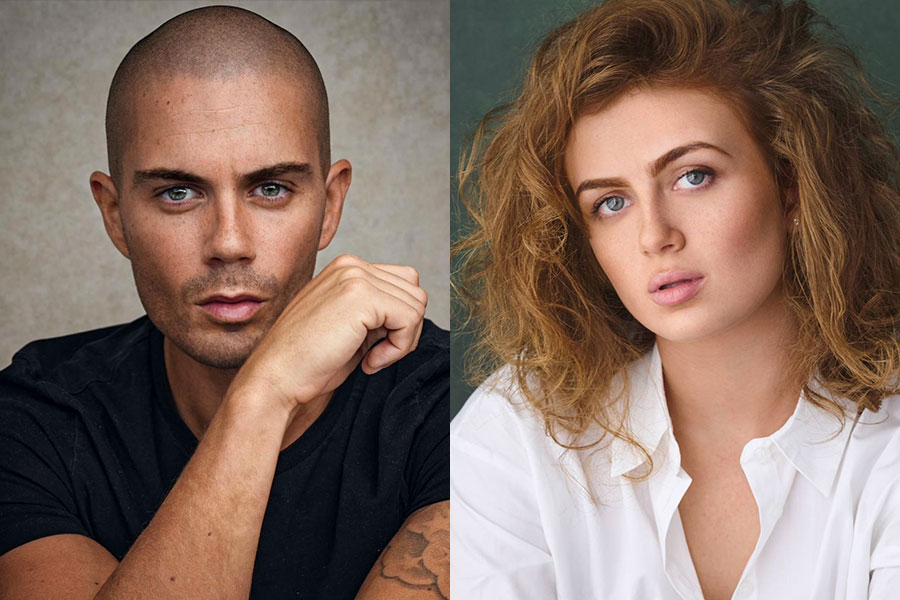

© Marc Brenner

Britain is split down the middle. Treachery is in the air, and saboteurs must be crushed. State surveillance spirals out of control, threat levels are inflated with invented terrors and war with Europe looms into view. The year isn’t 2017, but 1585. Queen Elizabeth I reigns supreme. Just about.

There’s so much resonance in Anders Lustgarten‘s examination of the Elizabethan surveillance system that it sometimes stifles the story itself. Francis Walsingham, the queen’s spymaster, who uses intelligence as much to manipulate his monarch as to iron out dissent against her, is truly a man of our times. First seen in a vast, papery vault, containing files on every conceivable security threat (Jesuits, Jesuit Sympathisers, potential Jesuit Sympathisers), he tracks and entraps the Catholics plotting against England’s Protestant queen and snuffs them out, one by one, like candles. To do so, he spins a web of deceit across the nation: false threats, double agents and fermented dissent. It threatens to entangle the spymaster himself.

At its best, The Secret Theatre is a rip roaring thriller that entwines the dark arts of espionage with those of politics. A quiet, cutthroat Machiavellian, the power behind the throne, Aidan McArdle‘s Walsingham has a lot in common with the Thomas Cromwell of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (not least in working his way up from nothing), and he’s every bit as transfixing in his inscrutable devilry. Dressed in black, the better to disappear into the shadows, he whips Tara Fitzgerald‘s brusque, rasping Elizabeth into a tizz until she’s paranoid putty in his scheming hands. Both of them play god: the white-faced, gold-gilt, heaven-sent monarch and the puppetmaster shaping history to suit his own ends.

At worst, however, allegory overtakes action, tipping the play towards contrivance and condescension – a quality exacerbated by Lustgarten’s habit of spelling out his point. "What happens when finally there are too many stories," Walsingham’s daughter Frances (Cassie Layton) asks accusingly. "Must you pull my strings?" His writing’s far less inclined to spell out the play’s context. It exists in the shadows of Schiller’s Mary Stuart, without matching that play’s historical clarity.

As such, a teasing, sometimes exhilarating plot becomes a packhorse piled high with present-day parallels: double agents as undercover cops, fake assassination attempts as staged terrorist spectacles, rumours concocted like the fakest fake news. By the time Jesuit leader Robert Southwell (Sam Marks) winds up on the rack, we’re onto torture techniques and Walsingham’s dissembling and dreadful inquisition comes unstuck in the face of absolute conviction; the martyr willing to die for his cause trumps a security system that stands only for itself. It all starts to feel like a conspiracy theory in breeches.

Overall, the thriller just about wins out. Lustgarten establishes the play’s world with deft swagger, plunging us into a time of rampant suspicion, where conspirators whisper in dark corners, hands hovering over their daggers. It’s perfectly at home in the candlelit glower of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, and lighting designer Malcolm Rippeth descends the play into darkness with a simmering, slow-burning menace. Jon Bausor’s design, with its maze of oak filing cabinets and its metallic sun, extends the stage’s possibility and instils Matthew Dunster‘s production with a real theatrical flair. Whatever the play’s faults, it’s worth watching – and closely.

The Secret Theatre runs at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse until 16 December